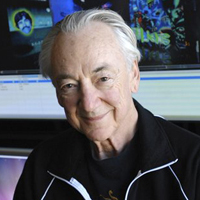

Charles Nesson

If he doesn’t have the right answers, that’s OK with Charles Nesson. In fact, many say the legendary eccentric—a proud pot smoker who loves poker, almost always records everything and has taught at Harvard Law School for more than 30 years—prefers exploring the unknown.

If he doesn’t have the right answers, that’s OK with Charles Nesson. In fact, many say the legendary eccentric—a proud pot smoker who loves poker, almost always records everything and has taught at Harvard Law School for more than 30 years—prefers exploring the unknown.“He doesn’t take pride in having this outward appearance of 100 percent competency,” says Gene Koo, a former fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, which Nesson founded in 1997.

Nesson was talking about cyberspace long before many colleagues saw its potential. Indeed, copyright scholar Lawrence Lessig dedicated his first book, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, to Nesson, “whose every idea seems crazy for about a year.”

This summer Nesson defended Boston University physics grad student Joel Tenenbaum, accused by the Recording Industry Association of America of illegally downloading and sharing music. Nesson says the case has been a great learning experience—despite the fact that Tenenbaum lost. So what could lawyers learn from Nesson?

“Embracing that willingness to fail,” says Koo, client manager at Blue State Digital, the Internet strategy group that played a large role in the Barack Obama presidential campaign. “Being willing to look silly or make mistakes—if you don’t do that you’re not going to learn.”

Indeed, Nesson’s actions in the RIAA trial looked mistaken to some. Opposing counsel charged that Nesson illegally recorded pre-trial hearings and depositions and posted them on his blog, eon. “The judge yelled me for doing it. She accused me of violating the Massachusetts wiretap statute,” Nesson said in an interview shortly before the U.S. District Court trial started in Boston. “The other side continuously makes noise about it as though I’m some kind of felon.”

He also sought to webcast the proceedings. The Internet, Nesson says, allows people to watch and learn as situations unfold. He believes the case is historic and he wants to share every moment.

In April the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the trial judge’s order giving permission for the webcasts. And unfortunately for Tenenbaum, the judge granted an RIAA pre-trial motion prohibiting a fair-use defense. The trial centered on damages: Nesson argued that if the jury found Tenenbaum committed copyright infringement, they should only impose minimal damages.

“Although it may have been illegal, it wasn’t unfair,” Nesson says. “It started bothering me—why are we talking about damages when the kid hasn’t done anything wrong?”

The jury rejected that point of view and assessed damages at $675,000, or $22,500 per song. It was reported that before the trial, the RIAA offered to settle the case for $4,000.

Risks—which Nesson advocates people to take—seem to figure in his strategy. Indeed, the trial could be seen as a poker hand that didn’t go how the player planned. Nesson, whose favorite card game is Texas Hold ‘em, uses poker to teach his students about taking chances and strategy.

“Students come in afraid of authority, knowing they will have spend their lives dealing with authority and thinking of it in terms of rules and that they have to learn the rules,” says Nesson. Learning poker, a game he has played since childhood, gets students to where they can think about making the rules of the game themselves, he says.

“You realize pretty quick that you’ve got to play your own chips, and you are fully equal to the rest of them,” Nesson says. “Once they get that, I feel like I’ve taught them something.”

Nesson rides his black Vespa scooter to work. In the winter he wears turtlenecks and sport coats. In the summer the turtleneck is replaced with a t-shirt, usually imprinted with something. When Nesson turned 70 in February, his Berkman Center colleagues threw him a birthday party. Everyone wore gray T-shirts illustrated with Nesson’s profile. Nesson got one too, and colleagues say he sometimes wears it to work.

He has longish gray hair, and a grandfatherly voice that quickly puts people at ease. In groups, Nesson can often be found sitting with his legs crossed in yoga’s lotus position.

“I have this very vivid image of him sitting there holding court, dressed more informally than other people from northern law schools,” says A. Michael Froomkin, a professor at the University of Miami (Fla.) School of Law. Froomkin wrote a chapter in a 1997 book Nesson co-edited, Borders in Cyberspace.

“He was older and more established than many of the people involved in this stuff, but was clearly young at heart,” Froomkin says. “He’d be great about introducing people. He seemed to really enjoy meeting young people and helping them.”

Nesson, who grew up in Massachusetts, comes from a wealthy family involved in real estate. His father also went to law school, but got caught cheating on the bar exam and was barred from practice, Nesson says. After finishing at Phillips Exeter Academy, Nesson went to Harvard University, where he studied math. He went on to Harvard Law to please his mother—“I really had no idea what a lawyer was.”—but it’s rumored he earned the school’s highest GPA since Felix Frankfurter, the U.S. Supreme Court justice who graduated in 1907.

Students seem to either hate or love Nesson. The gunners don’t know what to make of him, while many who hate law school say he’s incredibly refreshing.

“One thing he teaches is that law does not exist in a silo,” says Deborah Rosenbaum, a Harvard JD/MBA student going into her fourth year. She got to know Nesson in his law and public opinion course after she disagreed with a public relations person who spoke in the class. Rosenbaum worked in public relations before Harvard, and she’s most interested in Internet law. She’s been helping Nesson with the Tenebaum case. An appeal is planned.

And she’s a poker player. Taking risks from card playing to actuality, she says, has been interesting: The trial team posted a brief draft online as a collaborative lawyering exercise. They also used Twitter to publicize the case. Rosenbaum asked Nesson what the boundaries were, and he said “‘Nothing. Don’t worry about it, it’s going to be fine,’” she says.

But there was an Internet outcry, with some saying Nesson and his students (who weren’t even lawyers yet) should be disbarred for violating attorney-client privilege. Ultimately, the volume lowered and the brief-sharing was added to the many examples of Nesson’s unusual approach.

Nesson will tell you he approaches most everything while thinking of a cyber environment. He almost always carries a tape recorder in his pocket, and later downloads the recordings to share online. He also posts colleagues’ e-mails, even if they’d prefer he didn’t. Nesson’s electronic signature includes language stating as much. Sharing all information, he says, makes it easier for people to follow what’s happening.

“Technology lets you lay down track and create bits. Ultimately, cyberspace has all the bits you can reach for free on the Net,” he says, “which is just golden in terms of things to study.”

Watch Charles Nesson on a Google Tech Talks episode as he explains how Texas Hold’Em poker can be used as a tool for teaching core negotiation and business skills.