By Paul Lippe

Far and away the best analyst and predictor of the evolution of the legal marketplace is Richard Susskind, the U.K.-based academic and futurist.

Richard has a new book out called Tomorrow’s Lawyers: An Introduction to Your Future.

It is a slim and readable volume, laying out the case why law will be in a period of accelerating change, driven by technology (Richard tends to look at law through an IT lens), client demand and now opening up the legal provider market, led by the U.K.’s Clementi reforms which allow for non-lawyer ownership of law firms.

If you’re in any kind of management or leadership role in law (or you just care about your own career), I would say it’s a prerequisite to read Tomorrow’s Lawyers.

When I spoke to a meeting of law school Deans last month, several deans told me they had made Tomorrow’s Lawyers required reading for faculty, in part because they suspected students were already familiar, if not with the book, then certainly with the underlying theses.

Tomorrow’s Lawyers

My orientation has always been a little different from Richard’s, emphasizing more how law will “Normalize” to conform to other processes that clients manage and other markets for services. But in any event, we both certainly diverge from “Old Normal” law thinking, which emphasizes over and over again the uniqueness of lawyers and the uniqueness of every problem that lawyers face (what Richard calls “bespoke” or custom work).

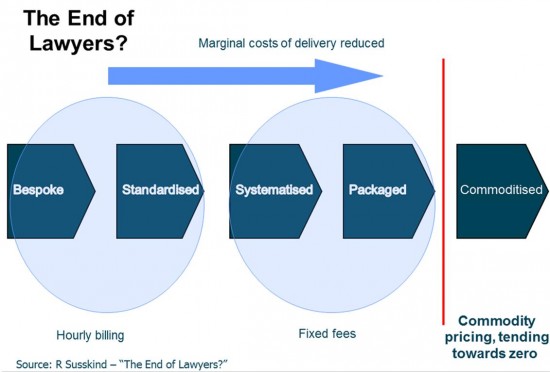

The core idea in Richard’s book (so rooted in IT thinking that when I showed it to a friend he said “yeah, that’s the slide we had in IT in 1996”) is that legal work will migrate from the bespoke (an elegant English word that seems to add 5 IQ points to anyone who says it) to commodity work (a dumb and counterproductive word which is only used to dismiss certain work as beneath the speaker’s dignity), evolving through intermediate stages of Standardisation (I’ll use his spelling, maybe I’ll get the 5 IQ point bonus as well), Systematisation and Packaging before reaching Commoditisation.

Lawyers deeply resist this notion, perhaps because our intellectual training in the Socratic method leads us to treat every issue as unique and requiring an individualized thought process, and because our ethical training emphasizes the intent of the lawyer, not the effect of the action.

Most folks who go in-house (as I did in 1988) experience a “now I get it” moment when they realize (i) most legal problems are quite similar to other legal problems, and so the best way to solve a problem is not by reference to their own thinking, but by understanding how that related problem was solved and (ii) if they want to be effective in an organization, they can’t adopt a posture of being ethically superior to other people, and so have to ground their recommendations in organizational long-term self-interest, not lawyer ethics.

Let me suggest that today’s “crisis” in legal education is rooted in law schools’ clinging to these twin beliefs in uniqueness, which are fine as a fundamental core, but which are very limiting if they are the extent of your thinking.

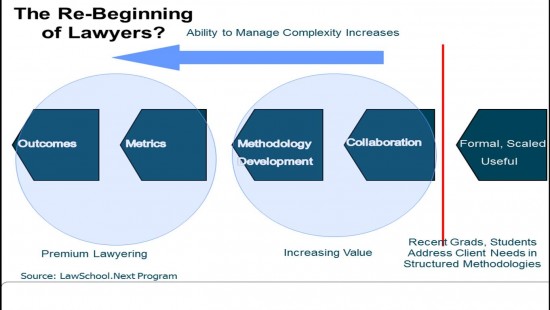

But what if we turn things around, what if we Run Richard in Reverse? Could we embrace the reality that much in law is repetitive, but that reality doesn’t denigrate the profession in any way? If we start by assuming most problems are alike and then move enthusiastically up the complexity ladder (as opposed to moving reluctantly down it, as we do today), perhaps both legal practice and legal education can unlock some opportunities. I’ll tweak Richard’s terms and say that the Susskind in Reverse hierarchy for legal education is:

• Formal

• Collaboration

• Methodology Development

• Assessment

• Outcomes

I’ll save discussion of the individual elements in the flow for another day, but let’s explore a specific problem for which Formal competence is a requirement, Dodd-Frank and its non-U.S. cousins.

One requirement in Dodd-Frank is for “living wills,” (PDF) by which all “Systematically Important Financial Institutions” must come up with a “Resolution and Recovery Plan (RRPs),” explaining how they could either (i) be broken up or (ii) survive the failure of one part of the bank.

There are interesting arguments on both sides of the “too big to fail” debate, but in the end they are all pretty indeterminate, and certainly don’t address the questions of how you would actually break up the banks without disrupting the economy (by the way, I was in favor of the break-up of IBM in the ‘70’s and Microsoft in the ‘90’s so I’m not an anti-breakup guy per se), keep them from re-assembling (see, e.g., AT&T) or how the U.S. or U.K. would be better off if all the big banks in the world were in China.

So I’m always less interested in abstract, Socratic-method fueled debates, and much more interested in the question of how to do you actually make things work, which brings me back to Formal work.

In order to develop the RRPs, banks will have to do some very Formal work to capture all the needed contract information. We are working with a number of banks which realize Dodd-Frank compliance (like most legal work) is a mix of bespoke and Formal work. Historically, the bespoke advisers have tried to do the Formal work as well, albeit at a premium price and not necessary premium level of execution. So banks are beginning to “unbundle,” and give work to different kinds of services providers.

As one customer put it to me “Long gone are the days when relationship (or panel) law firms can expect all work (or even all types of work in their category) to come their way. Clients are constantly looking to re-engineer how legal services are done to increase the yield for every dollar spent. Firms that try to hold onto work because they view it as bespoke will soon become irrelevant as in-house lawyers find other smarter ways to get the same outcome for less. It is the firms that embrace this New Normal who will succeed, by demonstrating their value to the client.”

From an educational standpoint, developing students’ competencies in Formal work will give them entree to large-scale projects, and they can quickly migrate up the complexity curve; from a client and societal outcome standpoint, “big enough to be efficient and compliant” is a much better place to get to than “too big to fail.”

Paul Lippe is the CEO of the Legal OnRamp, a Silicon Valley-based initiative founded in cooperation with Cisco Systems to improve legal quality and efficiency through collaboration, automation and process re-engineering.