By D. Casey Flaherty

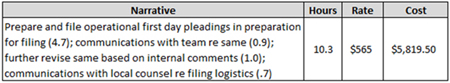

Quick, critique the following billing entry:

Invoice generation is an awful exercise. Invoice review may be worse. In a series of posts, I’ve used invoice review as a point of departure to talk about analytics and algorithms because the idea of machines taking on more of that thankless task should scare no one. Rather than the machine coming for your job, it is coming for a part of your job you hate. I, for one, welcome our new robot underlings.

D. Casey Flaherty.

Last post, however, I highlighted the application of algorithms to a large set of invoice data and suggested that it could do more than save institutional clients a few bucks. There is nothing wrong with saving money. Many corporations have shown a substantial return on investment from setting up in-house or third-party teams to rigorously review invoices. And there is a world not too different from the one we now occupy where those teams are augmented by technology like the one I was testing.

But the thing that has always troubled me about stringent invoice review is that it works too consistently. There are few trend lines that are as smooth as the decline in realizations over the last decade (see Chart 6). What’s truly astounding, however, is the constancy of the gap between what gets billed and what gets collected. Except for an unsurprising widening in 2008 and 2009, it looks like clients have a set amount they trim from firm invoices.

If your invoices are going to get cut the same amount no matter what, the rational response would seem to be to pad them, not by inventing work you didn’t do but by not pre-emptively cutting them as much as you otherwise would have. It reminds me of Hollywood in the days of strong censorship when outlandish scenes would be deliberately written into TV scripts so that in cutting them the censors could do their jobs without derailing the creative process.

This consistency suggests that we are just going through the motions rather than actually changing the underlying behavior. Which brings me back to that entry.

Before you read the text, you probably noticed that the entry violates most outside counsel billing guidelines, which require that each entry be a separate line item. When you did read it, you may have found that it violates other common guidelines, like prohibitions on internal communication (I’m not a fan).

You may have also concluded that it conveys precious little in the way of information about what the lawyer actually did (prepared in preparation, communicated). And if you did the math, you would have determined that those sub-entries add up to 7.3, not 10.3, hours. The lawyer overcharged the client by 3 hours, or 41 percent.

You caught all that. You know who didn’t? The lawyer who entered the time, and the people at the lawyer’s large, prestigious law firm who are responsible for reviewing invoices prior to submission. Why? Because no one went to law school to capture their day in six-minute increments. Because capturing your day in six-minute increments is excruciating. Because reviewing someone else recounting their workday in six-minute increments is excruciatingly boring.

Machines do not get bored. They also read and do math pretty quickly. That is why, in a matter of minutes, the technology I tested identified 166 of 14,744 entries where the subparts did not add up to the total time billed. It also marked many of those entries as vague and violative of the coded billing guidelines, just as it had flagged more than 20 percent of all the entries for one or more issue worthy of human attention.

Such a technology could certainly supplement an eagle-eyed client reviewer. But what makes the technology so attractive is that it could first be used by the law firm so the eagle-eyed client review is unnecessary. Instead of nitpicking and then crossing swords over information-poor invoices, the deployment of technology at the mesh point between client and the firm could shift us to a high-information equilibrium and permit us to focus on the big picture, the subject of the next post.

D. Casey Flaherty is a consultant at Procertas. Casey is an attorney who worked as both outside and inside counsel. He also serves on the advisory board of Nextlaw Labs. He is the primary author of Unless You Ask: A Guide for Law Departments to Get More from External Relationships, written and published in partnership with the ACC Legal Operations Section. Find more of his writing here. Connect with Casey on Twitter and LinkedIn. Or email [email protected].