Dec. 17, 1798: The Senate convenes the first impeachment

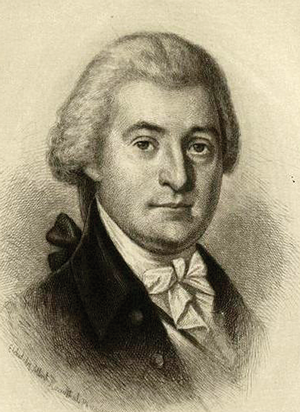

William Blount. Photographs courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

By the end of the 1700s, the United States had evolved into a land of genuine opportunity—one fully stocked with patriots and patriarchs, farmers and factory workers, tradesmen and traders, pioneers, adventurers and hustlers.

William Blount, born to a plantation-class family in North Carolina, could be described in many of these terms. A veteran of the Continental Army, a representative to the Continental Congress and one of the original signers of the Constitution, Blount was a friend of the nation’s first president, an esteemed voice in the nascent nation. But he also was an opportunist—an inveterate land speculator whose public responsibilities often were complicated by management of his highly leveraged holdings.

In 1790, George Washington named Blount governor of the newly formed Southwest Territory, an immense tract of frontier west of the Blue Ridge Mountains destined to become Tennessee. Blount owned vast acreage in the territory. Years earlier, he also had been instrumental in opening it to speculators like himself. In 1783, Blount introduced the “Land Grab Act,” which authorized the sale of non-Indian lands in the region as well as legislation that granted tracts to war veterans. Blount helped establish the cities of Knoxville and Nashville from the resulting settlements, and he negotiated a significant treaty with the Indians. He also was instrumental in setting the region on the path to statehood. When Tennessee was formally admitted in May 1796, Blount went to Philadelphia to represent the state as a U.S. senator.

On July 3, 1797, however, Blount was confronted in the Senate chambers with an extraordinary letter that detailed a plot devised by him and several other land speculators to help Britain gain control of Florida and Louisiana, then held by Spain. But as a result of its defeat by the French in the War of the Pyrenees, it was thought that Spain would soon give up those interests to France, thereby blocking access to ports on the Mississippi River and drastically reducing the value of millions of acres of Tennessee land held on fragile credit by Blount and other speculators.

A brawl in Congress between Connecticut Federalist Roger Griswold and Vermont Republican Matthew Lyon is one of many footnotes to the impeachment of Blount.

The plot proposed attacks by territorial militias—supported by British navy forces and friendly Indian nations—on New Orleans, Pensacola and the Missouri town of New Madrid. But the motley group of plotters he assembled proved unequal to the task. A Philadelphia physician, Nicholas Romayne, was dispatched to England to recruit investors. John Chisholm, a crude and colorful Tennessee woodsman, was sent to engage British government support. But Romayne was never enthusiastic about the plan, and the hard-drinking Chisholm was too willing to discuss it. By the time a Knoxville merchant turned over the Blount letter to authorities, the plot was all but dead.

Confronted with the letter, Blount was equivocal. Yet within four days, the House of Representatives recommended his impeachment on charges of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” On July 7, Blount returned to the Senate and refused to testify, and the following day the Senate voted to expel him.

But the matter of impeachment still existed. To escape potential criminal charges, Blount posted bond and fled to Tennessee, leaving the Senate to ponder deep into 1798 the implications of the plot and the legal boundaries of a first-ever impeachment. Romayne and Chisholm were arrested and confessed, and Blount’s own documents—seized during the investigation—revealed the plot in great detail.

Finally, on Dec. 17, 1798, the Senate convened a “High Court of Impeachment” to try several charges against Blount. Again, he did not appear before the Senate, but his lawyers argued that Blount could not be tried there. He no longer was a senator, and the very process of impeachment denied him his right to an actual criminal trial.

On Jan. 11, 1799, after about a week of debate, the Senate agreed, voting 14-11 to dismiss the impeachment proceedings. Blount died in March 1800, never having faced criminal charges.