July 13, 1863: Draft lottery sparks NYC riots

Photograph from Harper's Weekly via Wikimedia Commons.

The Enrollment Act of 1863 came at a bad time for New York Democrats. With Abraham Lincoln in the White House, abolitionists were gaining political strength, drawing crowds to their rallies. Under emancipation, the introduction of free black men to the cauldron of mostly German and Irish immigrants seemed foreboding to the Tammany Hall regime.

Support for Lincoln’s conduct of the Civil War was hardly unanimous in the North; by early July, many white workers in New York City saw conscription as an existential threat to a life and livelihood relatively untouched by the strife.

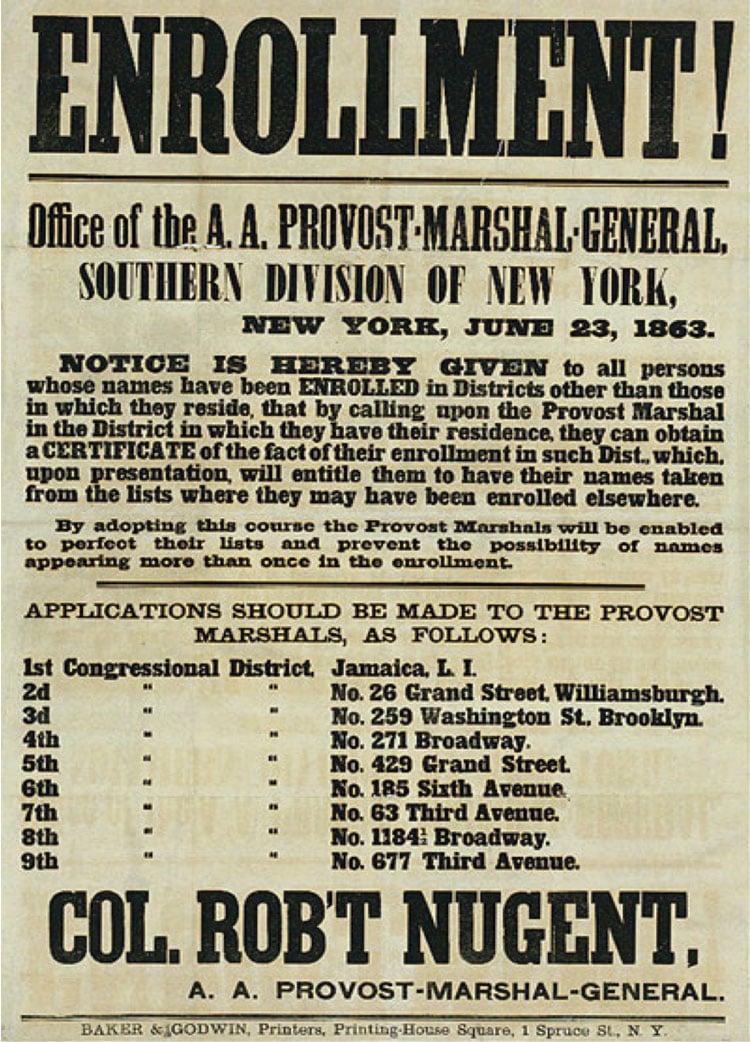

The act, which Lincoln signed in March, required male citizens between ages 20 and 45 to register for conscription, with each congressional district assigned a recruitment quota. The enlistment terms were left to individual states, and some offered generous bounties to attract recruits.

Photograph from U.S. Army via Wikimedia Commons.

In New York, a lottery was to determine conscription, but it had several unpopular exemptions: black men, whose citizenship was still a matter of national debate, and wealthy whites, who for $300 could purchase an exemption or hire a substitute draftee.

On Saturday, July 11, the lottery began smoothly at 677 Third Ave. in the 9th Congressional District. But by the time it resumed on Monday morning, July 13, white workers from several railroads and foundries had marched in unison to the site, recruiting others along the way.

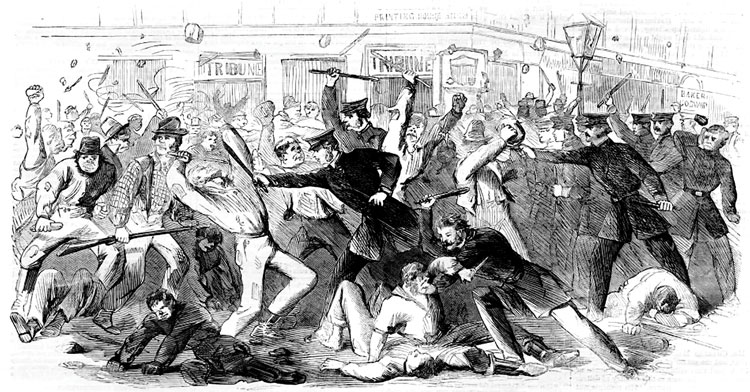

Anticipating trouble, officials delayed the lottery until police arrived. But the two dozen officers who responded were overmatched by the jeering mob. Shortly after the first names were pulled, jeers morphed into rocks and bricks. And as the mob moved in, officials abandoned the office to rioters. Soon furniture was destroyed, books and records strewn across the street, and the building—occupied by terrified families on the upper floors—set aflame.

Seemingly crazed by the fire, the mob moved through the city, swelling in number and indiscriminate wrath. When the police superintendent showed up, the horde beat him and destroyed his carriage. They set fire to the Bull’s Head Hotel, where the Union League was known to meet. The Marston & Co. armory was besieged and reduced to rubble. Two more enrollment offices were looted and burned. The home of the postmaster was torched along with a nearby police precinct.

Because the Battle of Gettysburg earlier in the month had sapped troop strength from the region, help from federal forces was slow to arrive. For four days, the rioters tumbled through the city unrestrained before sufficient troops could be mustered to restore the calm.

Roving gangs of Irish Catholics targeted Protestant churches and charities. For black residents, it was worse. Eleven black men were murdered for no apparent reason; countless others were beaten and maimed. Black families’ homes were destroyed. Even the Orphan Asylum for Colored Children on Fifth Avenue was torched, though its 230-plus residents managed to escape.

The mobs turned on newspapers perceived as Republican. At the New York Times, rioters were turned away by Gatling guns manned by Times staff. At abolitionist Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune, they listened to bulletins on the progress of their riot before attacking. Telegraph poles were toppled, train tracks upended, businesses gutted and burned.

Confronted by 6,000 troops and a Tammany Hall promise to pay the exemption fees of its loyalists, calm finally set in on Friday. Officials set the death toll at 119, with police and firefighters among the victims. Property damage ran into the millions, and 20 percent of the city’s black population, fearful of further violence, fled. Of the thousands who rioted, only 67 were convicted of any crime.