1935-1944: A New Deal

Photo of President Franklin D. Roosevelt by Vincenzio Laviosa/©Corbis

Alexander Hamilton had called the judiciary the “least dangerous branch,” but by the 1933 inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the U.S. Supreme Court was a caged tiger. Its justices had been appointed by a sequence of Republican presidents, backed by the capitalists of the Gilded Age, and the justices’ mission was the protection of individual property. Legal historians often refer to this period as the Lochner era, named for the landmark 1905 ruling rejecting a New York state law that would have limited bakery employees’ working hours in an effort to preserve their health. The court said the Constitution implied a “liberty of contract” favoring business owners and stood by laissez-faire government.

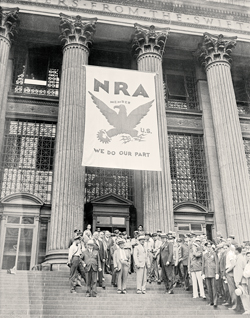

But the Great Depression wiped out that thinking as a quarter of the labor force became jobless, hungry and desperate. Roosevelt vowed to eliminate “fear itself,” and in his first 100 days began to install the New Deal, a flurry of domestic programs using government regulations to revive the sputtering economy. The statutory package, an alphabet soup of acronyms, included the National Industrial Recovery Act and the Agricultural Adjustment Act. The NIRA was an omnibus bill that sought cooperation among industries, workers and the government to provide fair competition and promote collective bargaining. It created the National Recovery Administration to oversee policies, and businesses proclaimed their alliance by posting its blue eagle logo. The AAA provided relief to farmers by paying them to reduce production, helping to cut crop surpluses and increase prices.

The short-lived National Recovery Administration drew up 500-plus industrial codes of fair practice. ©Corbis

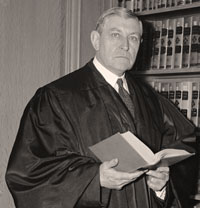

A seething Supreme Court was watching this active Congress and president churn out federal programs. Its conservative faction was led by four aging justices—Pierce Butler, James C. McReynolds, George Sutherland and Willis Van Devanter—referred to as the Four Horsemen. They were often joined by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Justice Owen J. Roberts, and together they resisted the New Deal. In 1935’s A.L.A. Schechter Poultry v. United States, the entire court invalidated the NIRA, saying the commerce clause stopped at state borders, barring Congress from its power of regulation. In 1936, the court split along partisan lines, with the Four Horsemen, Chief Justice Hughes and Justice Roberts rejecting the AAA. In another case, a furious Justice McReynolds dissented from the bench, proclaiming that the Constitution was dead and decrying Roosevelt as little more than the Roman Emperor Nero “at his worst.”

With his New Deal programs foundering, Roosevelt and his advisers came up with a counterattack. After his thunderous landslide re-election in 1936, he proposed a bill that would grant him the power to appoint an additional justice for every member of the court older than 70. He argued that the measure was meant to lighten the justices’ workload, but few were deceived: Roosevelt wanted his own justices. Republicans slammed Roosevelt’s arrogant “court-packing plan,” but public opinion was split. Nevertheless, the plan was never put into place. Justice Van Devanter announced he would retire; and then, curiously, Roberts, the pivotal justice, switched sides, joining the New Deal bloc and forming a majority favoring Roosevelt’s policies. Often referred to as the “switch in time that saved nine” justices, the reasons behind Roberts’ move are yet unknown and have been argued for decades since by legal historians.

Justice Owen Roberts originally sided with the Supreme Court’s Four Horsemen but would later support FDR’s New Deal.

In West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, Hughes’ 1937 decision upheld Washington state’s minimum wage law and sent the Lochner era to its grave. “The Constitution,” wrote Hughes, joined by Roberts, “does not speak of freedom of contract.” That year the court also upheld the Wagner Act, a crucial statute that created the National Labor Relations Board, this time supporting Congress’ control over intrastate commerce.

The expanded scope of the commerce clause, which validated much of the New Deal, became critical for Congress to enact far-reaching laws, especially in the civil rights era. In 1964, Congress based the Civil Rights Act—which prevented businesses from discriminating against African-American customers—on the clause; the Supreme Court upheld it in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States. But conservatives never stopped distrusting it. In the 1990s, the Rehnquist court turned over several statutes based on the commerce clause, among them the Gun-Free School Zones Act in 1995’s United States v. Lopez, and the Violence Against Women Act in United States v. Morrison in 2000. In his Lopez concurrence, Justice Clarence Thomas stated the case starkly: “Our case law has drifted far from the original understanding of the commerce clause. In a future case, we ought to temper our commerce clause jurisprudence.” The fate of the New Deal is likely to play out in the Supreme Court for decades to come.

100 Years of Law |

|

| « 1925-1934: On Trial: Science v. religion | 1945-1954: Footnote 4 » |