A Career Seized by the Horns

Sheila A. Flanagan

Photo by Chris Amaral

A love of animals and artisan cheese prompted Sheila A. Flanagan’s move to New York’s Adirondack Mountains from Oakland, Calif. She and her domestic partner planned to take their cheese making from a hobby to a business, but they wanted a dependable income to keep themselves and the animals fed.

So Flanagan, then a partner at Burnham Brown, asked management whether she could continue to work for the firm on a contract basis. Instead the firm offered her a senior-associate position, which Flanagan says wasn’t much of a pay cut. She defends toxic tort cases, and most of her work involves taking and defending telephonic medical-expert depositions. Flanagan makes those calls from a 50-acre goat farm in Thurman, N.Y.

Photo by Chris Amaral

If a deposition involves a significant amount of exhibits that Flanagan needs to see firsthand, she flies out of Albany; it’s the closest airport, though still an hour away from her farm. Burnham Brown generally covers travel costs, but Southwest Airlines has a hub in Albany that allows for cheaper airfare and is easier for Flanagan to navigate than a New York City airport.

It’s also easier for Flanagan to attend Midwest and East Coast depositions from her current location. That figured into her telecommuting arrangement, which started in July 2005. “I can attend depositions without having to charge clients an arm and a leg for me flying from San Francisco,” she says. “The other benefit is that I’m available 24/7. I’m not in traffic, I don’t have to worry about picking kids up at day care—everything is here on the farm.”

HAPPY LAWYER—GREAT CHEESE

Flanagan’s Nettle Meadow Goat Farm and Cheese Co. produces 50,000 pounds of cheese a year. With the help of four employees, Flanagan and her partner, Lorraine Lambiase, care for 200 goats, seven dogs and about 30 elderly farm animals, which live at their animal sanctuary and help give life to their company motto: “Happy Goats—Great Cheese.” The couple also give tours and sell cheese at the farm.

Flanagan’s love affair with artisanal cheese dates back to 2003 when she and Lambiase began raising Nigerian dwarf goats as a hobby. Before long they discovered that their pets’ milk made great cheese.

“We were big foodies when we lived in the Bay Area,” Flanagan says. “We were always very interested in cheese, and that kind of led to the intellectual question of ‘why is this cheese so good?’

“And it worked out,” she adds. It’s really been trial and error, and you learn more every year.”

Their cheese now is carried at Whole Foods Market stores along the Eastern Seaboard and at various New York City cheese shops. One of their most popular items is Kunik, a decadent, triple-cream cheese made from goat milk and Jersey cow cream. Flanagan recently added sheep to her menagerie. This spring, she plans to sell a cheese made from goat, cow and sheep milk.

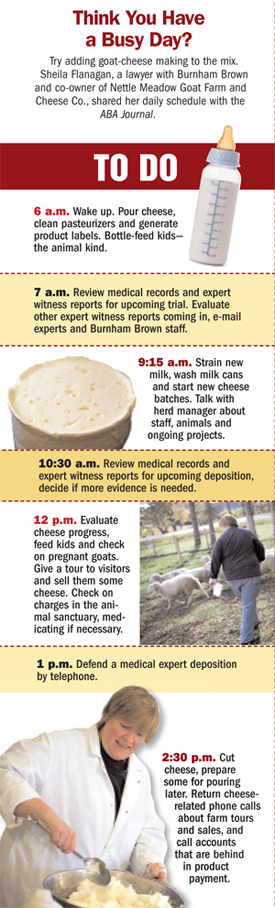

About three times a year Flanagan visits her Oakland office, paying for those trips herself. The time is like a vacation, given her cheese schedule. Days in Thurman start around 6 a.m. and are filled with legal and cheese-related tasks. She saves up vacation time for kidding season.

“You have to decide at the beginning of the day who’s doing the cheese room and who’s feeding the animals,” Flanagan says. While working on the farm, she generally doesn’t carry any sort of cell phone or pager because there’s no reception. She does carry a BlackBerry when filling in for their delivery truck driver.

Flanagan relies on dialup Internet service because her area is just now getting DSL. So she schedules downloading time to correspond with brief writing. By 7 a.m., she’s in her home office; and by the time her California colleagues and staff get to the office, she’s gotten a fair amount done.

Around 1 p.m., Flanagan takes an hourlong break for cheese-related tasks. Then it’s back to her home office for depositions. She usually works until 10 p.m. and prepares dinner in between depositions. Weekends involve more animal care and some legal work. For fun, she and Lambiase watch prerecorded television programs. They also go out to eat at some of the area’s nicer restaurants, but Flanagan says that only happens about three times a year.

“If I’m feeling really tired or really broke, which are the two things that get me down, I usually go look at the animals,” she adds.

But Flanagan also says that both sets of responsibilities inspire her. She’d be bored if she didn’t have the intellectual stimulation from her practice, while cheese making and caring for the animals keep her fulfilled.

Ultimately, she needs both. Organic hay costs about $206 a ton, and according to Flanagan it’s nearly impossible to run a cruelty-free organic farm without an additional income. In fact, she knows of at least four other nearby farmers who are also lawyers.

“Some people do think we’re a little crazy, especially when they see the work that’s involved,” she says. “You split your life so you’re doing two different things, and instead of one rat race it’s two. But for me it’s absolutely worth it.”

This article is the first in an occasional series about lawyers who’ve found unique ways to acheive work-life balance.