ABA entities pursue separate paths in search of ways to improve legal education

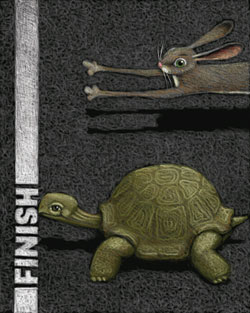

While the Standards Review Committee of the Section of Legal Education adn Admissions to the Bar continues to plod ahead in its fifth year, the Task Force on the Future of Legal Education seems to be taking a more nimble approach to its consideration of several big-picture issues relating to legal education. Shutterstock.com

On a Wednesday in late April, the ABA Task Force on the Future of Legal Education convened a daylong “miniconference” in Indianapolis to kick around ideas for some pretty radical changes in the legal education system.

Two days later—and 500 miles away—the Standards Review Committee of the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar settled in at a Washington, D.C., hotel for yet another grueling two-day drafting session in its long-running effort to overhaul the Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools. Eventually, the committee’s recommended changes will go to the section’s council for final action. The council is recognized by the U.S. Department of Education as the accrediting agency for programs in this country that lead to a JD degree.

Both efforts are ultimately aimed at improving the state of legal education, which is under fire from a number of directions. But in terms of the scope of their respective missions and the pace of their deliberations, the two projects couldn’t be more different.

The 19-member task force—which is made up of lawyers, judges, bar officials and academics—was created last August by then-ABA President Wm. T. (Bill) Robinson III. The task force is focusing its efforts primarily on economic issues related to legal education, licensing and the role of law schools in improving the delivery of legal services. Unlike the Standards Review Committee, the task force does not have to concern itself with the details and nuances of the accreditation standards. Instead, the task force is taking a big-picture approach to its work. To that end, it has been soliciting comments and hosting conferences like the one in Indianapolis, where it entertained suggestions from a group of invited experts that included reducing the traditional three-year law school model to two years and the creation of a category of limited-license legal technicians similar to nurse practitioners in the medical field.

ADVANCING THE TIMETABLE

The task force was originally given two years to come up with a set of recommendations that it would bring to the ABA’s policymaking House of Delegates for consideration. But recognizing both the gravity and the urgency of the issues, the task force has set its own target of issuing its recommendations later this fall, which means they could be considered by the House as early as February at the 2014 ABA Midyear Meeting in Chicago.

The Standards Review Committee has a much narrower focus than the task force, but also a much longer time frame for completing its assigned task.

The 14-member committee embarked on a comprehensive review of the accreditation standards in 2008. It is tasked with making sure that the standards (last updated in 2006) are still serving their intended purpose of ensuring that U.S. law schools provide a sound program of legal education that will, as stated in their preamble, “promote high standards of professional competence, responsibility and conduct” for members of the legal profession.

But that has proved to be a more difficult task than was first envisioned. The project, which was expected to take three years, is now in its fifth year and won’t be finished until this fall or early next year, says committee chair Jeffrey E. Lewis, a professor and dean emeritus at Saint Louis University School of Law. Under that time frame, it could be at least another year before the committee’s proposed changes are given final consideration by the section’s council.

At its April meeting, the committee agreed in principle to a simplified formula for satisfying the bar passage requirement contained in the standards. Under the current standard, a law school may meet the requirement in one of two ways: By showing that 75 percent of its graduates who took the bar exam in at least three of the previous five years passed, or by showing that its first-time bar passage rate was no more than 15 points below the average bar passage rate for ABA-approved law schools in states where its graduates took the bar.

Under the current draft of the proposed revision, which the committee will take up again at its meeting in July, a law school would only be required to show that 80 percent of its graduates who sat for the bar exam within two years after the year of their graduation passed. But a law school using that formula would have to account for all of its graduates, not just the 70 percent of graduates that it has to account for now under the current version of the standard.

LINEUP CHANGES

To date, the committee has forwarded to the council its proposed revisions to four of the standards’ seven chapters, all of which have been posted for notice and comment on the section website and were the subject of a public hearing in mid-May. The council has agreed to postpone final consideration of any proposed changes until the committee finishes work on all seven chapters.

But the committee still has some tough decisions to make, including whether the standards should require some form of job protections for all full-time faculty. The committee spent a lot of time discussing the merits of three alternative job-protection proposals at its April meeting, but opted to draft a fourth option for consideration at its July meeting that would eliminate such a requirement altogether.

Lewis told the ABA Journal that he expects the committee will complete its overhaul of the standards by early next year, and perhaps as soon as its meeting in October. But he says he’s more concerned about the quality of the final product than he is about the amount of time it takes to finish the job. “Our focus is on an excellent end product and not on timing,” he says.

David N. Yellen, the dean of Loyola University Chicago School of Law, is the only member of the Task Force on the Future of the Legal Profession who also has served on the legal education section’s Standards Review Committee during its current review period. He says the two entities are very different animals with very different purposes. The task force is a forward-looking, policy-oriented group that is considering the place of legal education in the larger world. The Standards Review Committee’s sole task is to examine the standards and propose amendments where it thinks appropriate. But he doesn’t see any inconsistencies in the work of the two entities. “They just have different roles to play,” he says.

But Yellen, who spent six years on the committee before leaving it in 2012, expressed frustration about how long the standards review process is taking, a situation he blames largely on a provision in the section’s bylaws that provides for the appointment of committee members to staggered two-year terms but prohibits them from serving more than six years total. The resulting turnover on the committee, he says, has made what should have been a three-year project an endeavor likely to last twice as long.

“The comprehensive review process should be done by the same group from start to finish without any turnover along the way,” he says.

Donald J. Polden, who served six years on the committee, including three as chair, agrees with Yellen’s assessment. Polden, who is dean at Santa Clara University School of Law, notes that the committee is just now finishing a project that he says was 90 percent complete when his term as chair ended in 2011. “The good news is that things are finally moving toward completion,” he says, “and the final work product looks a lot like what we tentatively approved two years ago.”