Creative expression programs for inmates help change the narrative

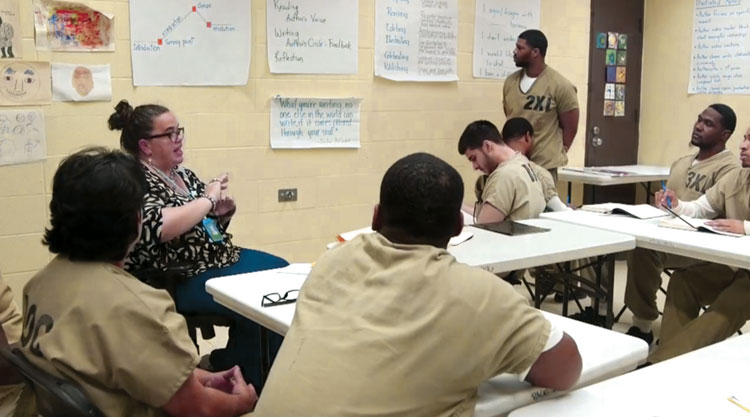

Publishing Celebration: Last April, the first class of inmate authors presented their final illustrated memoirs. Photo courtesy of ConTextos.

One book talks about a family’s love of dancing. Another is about the energizing freedom of a night on the town. A third explores the devastating loss of a sister to AIDS.

The narratives are different, but each of the works came from the same place: the maximum-security division of Chicago’s Cook County Jail.

For more than a year, teachers from the nonprofit ConTextos have been leading the Authors’ Circle, a memoir-writing class for detainees awaiting trial for violent offenses. Since the program launched in the jail in January 2017, three cohorts (about 65 men total) have participated, spending two hours a day three to four days a week for about four months reading, writing, revising, illustrating through collage and, finally, publishing their stories. The underlying philosophy of the program, which got its start in El Salvador, is that transformational change can happen to people when they reflect on their past experiences, thoughts, beliefs and attitudes—and tell their stories in a manner so that they’ll be heard.

“We talk a lot of the time about their emotions, traumas of the past,” says Lisa Kenner, chief educational officer with ConTextos. “It’s like canned fruits and vegetables. Even if we don’t cook it for dinner, it’s on our shelf.”

Kenner adds that the Authors’ Circle isn’t just about writing. It’s about reinforcing the value of every person. She says that by examining the past, authors—many of whom have experienced violence and trauma themselves—can feel empowered to alter their path in the future.

Across the country, creative expression programs in detention centers are blooming and take a variety of forms. In Miami, a program called Exchange for Change facilitates an anonymous writing exchange program that connects people in correctional and court-mandated facilities with students in high schools and universities. Ear Hustle—a podcast produced at California’s San Quentin State Prison by Earlonne Woods and Antwan Williams, both of whom are incarcerated, and artist Nigel Poor—shares stories about what life is like in prison. The organization PEN America runs a Prison Writing Program where mentors critique inmates’ writing by mail. The goal of all of the programs is to validate our shared humanity, create connections and learn from one another.

Lisa Kenner says the Authors’ Circle is about more than writing. By examining the past, writers can feel empowered to alter the future. Photo courtesy of ConTextos.

Anthony Barash, who is chairman of the ConTextos board and the former leader of the American Bar Association Center for Pro Bono, says that for the men in Cook County Jail, the writing program is frequently the first time they’ve been asked to tell their story. It’s had a dramatic impact.

“Over a period of time, relatively short, they begin to understand the consequences of their attitude, of their behavior, of their response. And they learn that they have choices that they can make. And they can, in their own ways, reflect on choices that they’ve made, and they develop the capacity to essentially see and make different choices,” says Barash.

Debra Gittler, ConTextos founder and executive director. Photo courtesy of ConTextos.

Authors’ Circle participants live together in the same area of the facility during the program. Over time, they begin to trust one another, find commonalities, open up and understand that, even in jail, they’re part of a community, Barash notes. As they make those connections, violent incidents and infractions within their section of the jail have decreased dramatically, he says. That change in attitude and response is something that he hopes will last—not just after the program ends, but for generations.

“My hope is that we develop a critical mass of people who work with our program, who are touched by our program, who in turn go into the community and demonstrate by who they are, what they do and the paths they take, that change can happen. That violent behavior can be mitigated,” Barash says. “That there are choices.”