Jeff's Law

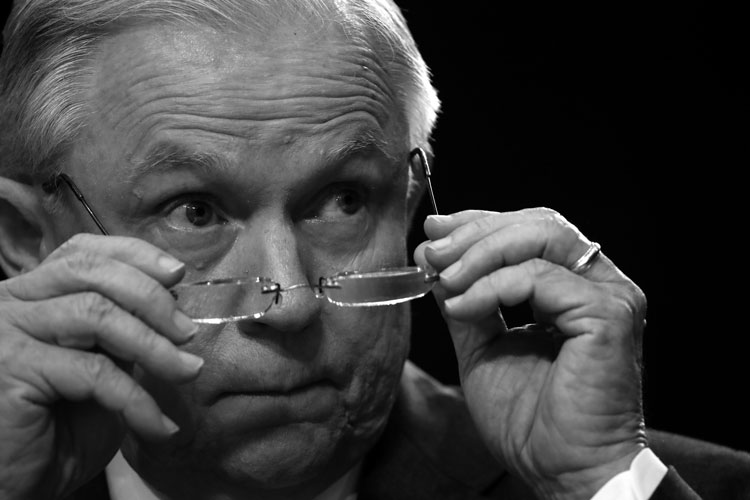

Photo of Attorney General Jeff Sessions by AP Images

The attorney general sees his role as pushing present-day law enforcement toward a rose-colored past.

Editor’s Note: U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions is a central character in numerous legal issues at the top of today’s headlines. But what has made him rise from growing up in rural Alabama to becoming the nation’s top law enforcer? The ABA Journal is providing a prepublication look at a feature profile of Sessions to give some background and context to the man and his actions.

U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions regularly goes a bit off script from prepared speeches, even more so when addressing groups with which he is particularly close.

He jettisoned the entire text in February at the winter meeting of the National Association of Attorneys General, where he was Alabama’s representative for two years beginning in 1995. He talked about a growing crime wave, albeit one whose seriousness is questioned by many experts.

“I’ve got a nice speech here, but maybe we can just chat,” Sessions said after being greeted with a standing ovation. And chat he did in his folksy, earnest way, occasionally bouncing up on the balls of his feet in his compact and tightly wound fashion, eyes darting about as he turned his head and gazed side to side with occasional smiles.

In the unused, written version of his speech, there were details to illustrate a main theme—an increase in violent crime. It mentioned citizens fearing for their lives when leaving home; parents putting children in bathtubs to avoid stray bullets; and entire neighborhoods dominated by drug dealers, gangs and other violent criminals.

It didn’t offer context, but he was highlighting problems in mostly urban environments. But, off the cuff, Sessions—who grew up in a tiny, unincorporated rural Alabama community in the 1950s and ’60s—made this point about fear earlier in his speech, and it was simpler and personal.

Crime had been increasing in the 1960s and was still doing so in 1975 when he became an assistant U.S. attorney, Sessions explained, and “this was a bad trend.”

“The mentality was that nothing could be done,” he explained. That mentality believed prisons made things worse, criminals were victims, police were victims, victims were victims. “Everybody was a victim, and we couldn’t do much about it.”

Those concerns led to “burglar bars, burglar alarms” on everyone’s homes.

“Never been done before; people never locked their doors before in the ’50s,” he said, his voice rising in pitch with the last phrase, as if it were yesterday. “And so, this was a big change.”

For most of those who either lived in the 1950s or are steeped in the sweet and uncomplicated way of life portrayed in TV shows of the day, that culture—somewhat idealized—is long gone. And probably most people in towns and cities larger than Hybart, where Sessions’ father ran a general store, locked their doors at night back then.

Sessions believes the era he remembers for its safe innocence can and should be restored. From the moment he was sworn in as attorney general, he has worked directly through policy to make it happen.

And he has been turning upside down a lot of accepted wisdom and policy in matters of crime, punishment and civil rights, such as voting rights and specific protections concerning sexual orientation.

It leaves many experts bemused.

In May, the American Society of Criminology, an organization of academics, issued a statement saying the Trump administration’s handling of criminal justice had come to “demonstrate an incongruity between administration policy efforts and well-established science about causes and consequences of crime.”

But Sessions appeals more to average people on the street, who likely see themselves as potential crime victims, says Douglas A. Berman, who teaches criminal law at Ohio State University and operates the blog Sentencing Law and Policy.

“You’ve got to understand who he is and what he cares about,” says Berman, who finds Sessions’ motives genuine. “I continue to be hopeful that he will be not only measured but ultimately effective.”

Berman adds that we have an opioid epidemic and significant violent crime problems, particularly in some cities, “and I want him to be successful.”

Much discussion and debate has surrounded the attorney general, especially in midsummer when the man who appointed him seemed dead set on driving him out of office, if not out of town. Still, as of the ABA Journal deadline in early September, he was hanging tough. Sessions’ reputation is that he’s not one to run or to swiftly change directions.

And his recipe for success is simple: Arrest criminals and put them behind bars.

EARLY SUPPORT: Sessions was the first senator to stand behind Donald Trump after he announced his presidential campaign. AP Images

JOINT MESSAGE

Sessions was the first senator to back Donald Trump during the presidential campaign, and they were together on message from the beginning: Fear of immigrants and crime struck a chord with a lot of Americans. The two of them went at that chord in tremolo, with a pick. Sessions had played these themes for decades, while the president came to the effort in more recent years.

“Sessions has never struck me as a particularly complex person,” explains Jonathan Turley, a professor at George Washington University Law School who differs with the attorney general on many issues but believes Sessions is motivated by his views as “first principles.” Turley adds that critics wrongly “ascribe darkest motivations to his conduct.”

“He’s very straightforward and exactly as he appears, quite open and frank about his views,” Turley continues. “I’ve worked with a lot of members of Congress, and it’s not uncommon for them to say in private something diametrically opposed to what they say publicly. He’s one of a couple of senators I’ve found entirely consistent both privately and in public.”

In one jolting announcement after another since he became attorney general, Sessions has challenged or reversed policies he believes are soft on criminals and threaten public safety, often despite evidence-based findings that suggest otherwise.

Just a few of those initiatives:

- Ordering U.S. attorneys to charge the most serious crimes possible under the available facts, overturning then-Attorney General Eric Holder’s memo calling for lesser charges to avoid mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent, low-level drug offenders.

- Rescinding former President Barack Obama’s order to phase out the use of private prisons because they provide less safety and cost more.

- Reviving the use of civil asset forfeiture, permitting law enforcement agencies to seize money and property from people not yet even charged with crimes.

“He views crime in a very linear fashion,” says Turley. “The Obama administration sometimes seemed to relish the complexity of modern crime. They almost had a slogan posted above the door: ‘It’s not that simple.’ We’d be better off if we could find a middle ground.”

As Sessions sees it, 1970s tough-on-crime policies and the launch of the war on drugs in the 1980s were major factors in the subsequent drop in crime rates, which peaked in 1991 and declined up until 2014. Now we’re backsliding, according to Sessions, who told the gathering of state attorneys general that “maybe we even got a bit overconfident when we’ve seen crime rates decline for so long.” He called for a return to “the ideas that reduce crimes.”

In his prepared speech for the National District Attorneys Association in July, Sessions described “a multifront battle” with increasing violent crime, vicious gangs, an opioid epidemic, and threats from terrorism and human traffickers, “combined with a culture in which family and discipline seems to be eroding further.”

Sessions noted, “Per capita homicide rates are up in 27 of our 35 largest cities,” representing “a sharp reversal of decades of progress. My best judgment is that this rise is not an aberration or a blip. ... Yielding to the trend is not an option for America, and certainly not to us.”

James Lynch, president of the American Society of Criminology, believes the AG’s statistical emphasis is misleading.

“You can mess around the edges about whether homicides are going up in selected cities, but it’s not catastrophic or other hyperbole,” he says. “It doesn’t look like we’re going to get the kind of broad-based increases like the crime wave that started about 1987 through about 1994 in almost every large city. [That tracks the crack cocaine epidemic.] Since then it’s been bouncing around in specific cities, getting bad and then better.”

Sessions’ approach to crime, punishment and civil rights is the same now as when President Ronald Reagan appointed him in 1981, at age 35, as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Alabama. After 12 years in that job, he had to move on when Bill Clinton was elected president, and Sessions soon was elected state attorney general.