Flunking Civics: Why America's Kids Know So Little

Parents traditionally worry about what their children are learning in school, but it’s what those students are not learning that’s even more unsettling. Only one state deserved a rating of A when it came to teaching its students American history, according to a recent study. Most states fall in the category of “mediocre to awful.”

The study ranked history standards in 49 states and the District of Columbia (Rhode Island has no mandatory history standards, only suggested guidelines) for “content and rigor” and “clarity and specificity” on a scale of A to F. Only South Carolina got straight A’s.

See other article features:

- Take our 10-question civics quiz.

- Watch our video of a civics pop survey of passersby at Chicago’s Millennium Park one afternoon in mid-March

- See the related photo gallery.

- Read about the ABA’s involvement in civic education.

Nine states’ standards earned a grade of A- or B. But a majority of states—28 in all—had standards ratings of D or F, the study found.

The findings confirm what the study’s authors have long suspected, says Chester E. Finn Jr., president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, the Washington, D.C.-based educational think tank that conducted the study.

“No wonder so many Americans know so little about our nation’s past,” he says.

And Americans’ lack of civic knowledge disturbs some of the most respected figures in government and politics.

“When I went to school, we had all kinds of courses on civics and government,” says retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who is pushing to revive civic education. “Today, at least half of the states don’t even require high school students to take civics; only three states require it in middle school.”

Teaching government, civics and history is becoming a more pressing need than before. With school cutbacks, the Internet distracting students, and the disappearance of traditional newspapers and TV news shows that objectively report information, youngsters have become increasingly disengaged from civic and political life, experts say.

Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts Classic Stock/Corbis

YOUNG NONVOTERS CITED

Those under the age of 25 are less likely to vote than were their elders or younger people in previous decades, according to a 2003 report by the Silver Spring, Md.-based Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, a coalition of about 40 organizations, including the American Bar Association. According to the report, students also are less interested in public or political issues than were previous generations, and they exhibit gaps in their knowledge of fundamental democratic principles and processes.

“As a result,” the report said, “many young Americans are not prepared to participate fully in our democracy now and when they become adults.”

The report also found that schools in many ways are uniquely suited to addressing the situation because they reach virtually every young person in the country, they represent a community of different views and opinions, and they are well-equipped to deal with the cognitive aspects of good citizenship, such as critical thinking and deliberation.

Other studies have also documented the need for improvement and reform in civic education. The Denver-based National Center for Learning and Citizenship maintains a database on citizenship education, which shows that while 49 states have standards that address citizenship, fewer than half have any testing or assessment programs in place.

And the National Center for Education Statistics in Washington, D.C.—which issues periodic progress reports on what students know in various subject areas, known informally as the Nation’s Report Card—found that only 27 percent of 12th graders in 2006 were proficient in civics and government. (The center reassessed students’ knowledge of civics and government in 2010; the results are due later this year.)

The problem is exacerbated by evidence of what researchers describe as a growing “civic achievement gap” between white, wealthy, native-born youths—who demonstrate consistently higher levels of civic and political knowledge, skills, attitudes and participation—and poor, nonwhite and immigrant youths, who are thus at a disadvantage politically.

Since the late 1990s, when American students tested poorly in reading, science and math against students from 20 other Western nations, federal educational policy has focused strongly on those three subjects at the expense of history, social studies, government and civics.

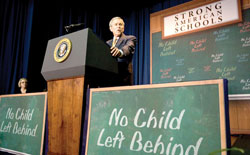

Photo by AP/J. Scott Applewhite

That trend began in 2001 with the Bush administration’s landmark No Child Left Behind Act, which gives priority to federal funding for efforts to improve student performance in reading and math, skills that are considered fundamental to student success in the workplace. The program continues under the Obama administration’s support for so-called STEM programs, which reward student achievement in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math.

Educators fear that this long-range focus on a few limited subjects that are considered fundamental to student success is squeezing out the amount of time and effort devoted to subjects considered nonfundamental, such as history, social science, government and civics.

And they say the evidence of that continues to mount—both empirically and anecdotally.

In 2006, the Center on Education Policy, an independent advocate for public education, conducted a survey on the effects of No Child Left Behind on elementary school instruction. Of the school districts surveyed, 71 percent said they were spending less time on subjects like social studies, music and art to devote more time to reading and math, the two subjects tested under NCLB.

A 2007 survey of 350 school districts nationwide by the Center on Education Policy found that instructional time for subjects not tested by the NCLB had fallen by one-third since the law was passed.

NOT JUST KIDS

Adults, perhaps unsurprisingly, don’t appear to have a better grasp of law, history or government—all of which could be considered essential to civic responsibilities—than students do.

A 2005 survey by the ABA, for example, found that nearly half of all Americans were unable to correctly identify the three branches of government. A FindLaw survey that same year found that only 57 percent of Americans could name any Supreme Court justice.

Photo of U.S. Rep. Michele Bachmann of Minnesota by AP Photo/Jim Mone

Some public figures seem to know as little about history—and geography—as many private citizens. In a speech in March, U.S. Rep. Michele Bachmann of Minnesota, a possible Republican candidate for president in 2012, identified New Hampshire—instead of Massachusetts—as the “state where the shot was heard around the world.” And in 2008 when he was the Democratic candidate for vice president, Joe Biden declared that Franklin D. Roosevelt had educated the nation about the 1929 stock market crash—on television.

At least one expert says that the picture is not as bleak as others say.

While it’s true that most young Americans don’t know all that much about politics and government, they know as much as their parents did and more than their peers in other countries, says Peter Levine, director of the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, and one of the leading researchers in the field.

Young people also vote, Levine says. Though voter turnout among younger voters was down in 2010 from 2008, there is no evidence of a systematic decline in youth voting compared with the 1980s and 1990s, he says. And volunteering is at record levels.

Levine says that schools are still teaching civics as much as or more than ever before. The amount of time devoted to social studies in elementary and middle school has remained pretty constant over the years, he says, and the amount of time devoted to social studies in high school is up substantially, although the mix of courses has changed appreciably since the 1950s. Civics and problem- or discussion-oriented classes are less common today than they were in the 1950s, he says, but political science, economics and social studies classes are more common.

That’s not to suggest that all is rosy, Levine cautions. Teaching civics is only partly the job of the schools. Other providers of such teaching—newspapers, unions, membership organizations and community groups— aren’t taking up the slack. People are sorting themselves into more politically and ideologically homogenous communities than they used to, he says. And the gap between the haves and the have-nots when it comes to opportunities for civic engagement is bad and getting worse.

“Democracy depends on citizens who are motivated and able to participate effectively in the process,” Levine says. “Otherwise, we run the risk of replicating an unjust democracy in the future.”

Advocates of better civic learning aren’t waiting around for that to happen. They say the cause is too important to ignore and the consequences of not acting too grave to contemplate.

HIGH-LEVEL HELP

ABA President Stephen N. Zack, for one, has made the improvement of civic education in this country one of his top priorities.

Zack has lobbied U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan to make civic education a national priority. He also persuaded the ABA Board of Governors to create a Commission on Civic Education in the Nation’s Schools to serve as both an advocate for and a provider of effective, high-quality civic education programs.

Zack says our country’s future as a democracy depends on the integrity of our legal institutions, our commitment to justice and our understanding of constitutional self-government. But he says that future is now being threatened by a basic lack of understanding among Americans about what a democracy is and how it’s supposed to work.

He cites figures showing that two-thirds of all Americans can’t correctly identify the three branches of government, and that three out of four people don’t know that the Bill of Rights protects religious freedom.

“It would be amusing if it weren’t so tragic,” he says. “But the sad fact is this is a pervasive problem that starts in the schools and permeates our entire society.”

Zack also notes the outrage many people feel when the U.S. Supreme Court issues a controversial First Amendment ruling, as it did in early March, when it upheld the right of hate groups to protest at military funerals; and in 1989, when it affirmed the right of an anti-war protester to burn the American flag.

“People don’t realize that while the executive and legislative branches are based on majority opinion, the judiciary is beholden only to the Constitution,” he says.

For Zack, who fled Cuba as a 14-year-old boy during the revolution there in 1961, the cause is personal. He still keeps a copy of the old Cuban constitution, which he says was nearly identical to ours, on his desk to remind him that words alone will not protect our rights.

“We all need to do our part to ensure that the words in the Constitution are not just words,” Zack says.

The ABA commission created by the board at Zack’s urging is sponsoring a series of civics and law academies at various locations around the country where lawyers, judges, teachers and other community leaders can teach students in middle and high school about the law and the Constitution, as well as the importance of civic engagement.

The first such academy, co-sponsored by Florida International University’s College of Law, took place on the school’s Miami campus over the President’s Day weekend. A second—co-sponsored by Close Up, a Washington, D.C.-based citizenship education organization—was scheduled for the last week of April. Other academies are in the works.

The commission has also created a resource guide and a website where bar associations, law schools, courts, civic organizations, young lawyer affiliates and others interested in sponsoring such a program can find suggested curricula, formats, lesson plans, strategies and other information.

In addition, the commission has conducted an online survey of bar associations and other organizations to compile a comprehensive and up-to-date database of existing civic education activities and to help identify what types of programs work best.

Photo of Sandra Day O’Connor by AP/Carolyn Kaster

SUPREME ASSISTANCE

Retired Justice O’Connor, a longtime champion of civic education, serves as a special adviser to the commission. She describes her duties in the role of special adviser as “putting my two cents’ worth in” and encouraging lawyers and others to do whatever they can to help. But she is also a tireless crusader and forceful advocate for the cause.

O’Connor says she first began to realize how little people know about the way government works during her years as a judge, when she became increasingly alarmed by the efforts of lawmakers and others to politicize the judiciary and “punish” judges for their decisions.

That led her—along with Justice Stephen G. Breyer—to convene a conference on the state of the judiciary in 2006 to try to get to the root of the problem. The overwhelming consensus of the attendees was that public education is the key to preserving the independence of the judiciary and sustaining our constitutional democracy.

O’Connor thinks the evidence is pretty convincing. “There are all kinds of polls out there showing that barely one out of three Americans can name the three branches of government, let alone describe what they do,” she says.

To help fill that gap, O’Connor joined forces with experts at Georgetown University law school, Arizona State University and others to develop an interactive, Web-based educational project aimed at teaching students about civics and inspiring them to become active participants in our nation’s democracy.

The website—at iCivics.org—features lesson plans, Web quests, discussion forums and games designed to teach students about the Constitution, the three branches of government, and the rights and responsibilities of citizenship.

The project, which has been up and running for six years, is now being used in all 50 states, O’Connor says, though admittedly more so in some states than in others. But her goal is to get it into every school in America.

The only thing standing in the way, she says, is bureaucracy. “It’s free, it’s teacher-friendly and it’s a lot of fun for the kids.”

Sorely needed, too, as O’Connor is quick to point out.

Because an understanding of and appreciation for democracy is not an inherited trait that is passed along through the gene pool, she says.

“It has to be taught anew to each generation.”

Sidebar

American Know-How & the ABA

The ABA’s involvement in civic education dates back to the early 1920s, when it joined calls for the study of the Constitution in the nation’s schools as a bulwark against radicalism and for the “Americanization” of immigrants, according to R. Freeman Butts in his 1988 book, The Morality of Democratic Citizenship: Goals for Civic Education in the Republic’s Third Century.

ABA President Frank J. Hogan,

photo

courtesy of the

Library of Congress

That involvement continued in the 1930s, when the ABA, under President Frank J. Hogan, created a special committee on the Bill of Rights to defend the rights and liberties of individuals. The committee filed an amicus brief on behalf of two Jehovah’s Witness students who had been expelled from school for refusing to salute the American flag during the Pledge of Allegiance. The students lost before the U.S. Supreme Court in Minersville School District v. Gobitis in 1940.

The committee also prepared a brief in a second flag-salute case that came before the court in 1943. This time, in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, the court reversed its earlier decision and sided with the students.

World War II dampened whatever impetus there was at the time for teaching the Constitution and the Bill of Rights in the schools, according to Butts’ book. And the 1950s saw a resurgence of conservatism that helped drive progressive social studies teaching out of the schools and resulted in laws in 30 states requiring teachers to sign loyalty oaths.

But the 1960s and 1970s brought about a renewed interest in the teaching of social studies and law-related education in the schools, with an emphasis on individual rights and liberties and the responsibilities of citizenship, Butts wrote.

Photo of ABA President Leon Jaworski by AP Photo

The ABA’s efforts on that front have been ongoing since 1971, when then-ABA President Leon Jaworski—who would later become famous as the Watergate special prosecutor—established a special committee on youth education for citizenship, the genesis for what 12 years later became the ABA’s Division for Public Education.

The division, created to promote public understanding of the law and its role in society, today acts as a proponent of civic education and as a civic educator. It provides national leadership for law-related and civic education efforts in this country, conducts its own educational programs, develops resource material, offers technical assistance and information clearinghouse services, presents awards for civic activism, and fosters partnerships among like-minded bar associations, educational institutions, civic organizations and others.

The ABA House of Delegates has been a longtime, consistent supporter of law-related civic education efforts, beginning in the 1970s. It has passed six such resolutions in the past seven years alone, including one at last year’s annual meeting in San Francisco urging all lawyers to consider it part of their fundamental duty to help ensure that students get a high-quality civic education, and one at this year’s midyear meeting in Atlanta urging the federal government to require the teaching of civics in public schools and to provide grant funding for such efforts.