Homing in on Foreclosure

Illustration by Stuart Bradford

Register for this month’s CLE, “What We’ve Learned from the Real Estate Crisis—So Far,” from 1-2 p.m. ET on Wednesday, July 16.

If you want to find ground zero of the implosion in the U.S. real estate market, just look for people like Nettie and Leroy Sallet.

The Sallets needed some money. Desperately. In poor health and elderly, they were scraping by on Social Security checks that barely gave them enough to buy food and medicine. Then Leroy fell ill, leaving them with a daunting pile of medical bills. And their modest home was in urgent need of repairs. They wanted to replace the carpeting, for instance, because it had become so badly worn that it was hard for them to maneuver their walkers over its uneven surface.

It was 2006, and housing prices were sky-high in the Jacksonville, Fla., area, so Nettie and Leroy decided to raise some money by taking out a loan against their home. They didn’t seek counsel from a lawyer, and in May 2006 they signed the loan documents in their living room.

From the start, the Sallets were in trouble. After paying various fees and charges, they received less cash from the loan than they had anticipated. They were able to pay off Leroy’s medical bills, but there was little left over for the anticipated home repairs. That worn-out carpet had to stay.

Even worse, the loan payments were much bigger than the Sallets expected. A month after the loan was signed, they defaulted; and soon after that, they were facing a foreclosure action. They feared they would lose their home of 24 years.

It was only after finally seeking legal help that the Sallets learned what was in the documents they had signed. “They had no idea, until they got served with foreclosure papers, that they had signed two loans,” says April Charney, an attorney with Jacksonville Area Legal Aid, who is representing the couple. “That’s how elderly and infirm they are. They thought they were getting a loan that would help them meet some expenses and make some repairs to their home. Instead, they got two loans they couldn’t afford. They never had a prayer of making the payments.”

With Charney’s help, the Sallets are fighting the foreclosure action in court, alleging that the lender engaged in deceptive and predatory practices, wrongfully added late fees and other charges, and violated federal law by failing to offer debt counseling to the Sallets before commencing foreclosure proceedings. For now, they are still in their home.

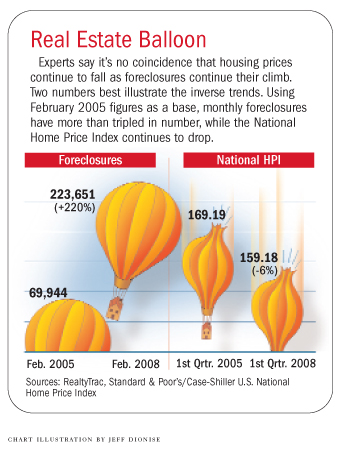

Nettie and Leroy Sallet are not alone in their predicament. Foreclosure filings in the first quarter of 2008 increased by 112 percent over the same period in 2007, according to RealtyTrac, an online real estate site that covers the foreclosure market. And the trend continued in April, reports RealtyTrac, which defines foreclosure filings as default notices, auction sale notices and bank repossessions. The 243,353 filings in April—one in every 519 U.S. households—represent an increase of nearly 65 percent over April 2007.

MORE TROUBLE AHEAD

The situation is likely to get worse. a report issued in April by the Pew Charitable Trusts projects that one in 33 current U.S. homeowners will be in foreclosure, mostly within the next two years, as a direct result of subprime loans made in 2005 and 2006. And the crisis is not restricted to just a few states, says the report, which found that foreclosures increased by at least 20 percent between December 2006 and December 2007 in 47 states and the District of Columbia.

Foreclosures are a key factor in the downward spiral of the U.S. real estate market.

Only a few years ago, both lenders and borrowers succumbed to the temptations of subprime and gimmick loans in the belief that steadily rising housing values would offset their risks.

“While real estate values were going up, that system worked,” says Patrick E. Mears, a partner in the Grand Rapids, Mich., office of Barnes & Thornburg who chairs the Real Estate Financing Group in the ABA Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law. “Equity in the home would go up during the period of the teaser rate, so when the interest rate kicked up substantially, the homeowners would refinance and get a 30-year fixed-rate loan.”

By 2004, many institutions were knowingly lending money to people who were unlikely to make their payments. When borrowers overstated their income, for instance, lenders and mortgage brokers often looked the other way or actively colluded with unqualified borrowers in order to have the loans approved. Sometimes lenders and brokers pushed borrowers into adjustable-rate loans even when they qualified for more affordable fixed-rate loans, which were less profitable for lenders.

“A lot of fraud came from mortgage brokers who put people into subprime loans when they didn’t need to be, because it got them more money. A higher interest rate meant a higher broker fee,” says Marjorie R. Bardwell, vice president and senior underwriting counsel for the Fidelity National Family of Title Insurance Cos in Chicago. She chairs the Residential, Multi-Family and Special Use Group in the real property section.

But when house prices stopped going up, many borrowers couldn’t refinance their way out of adjustable-rate loans when the monthly payments jumped, and they slipped into foreclosure. The growing numbers of foreclosures helped create a glut of houses on the market, which pushed prices lower, and that in turn led to still more foreclosures. And just when more homeowners were seeking to refinance their mortgages, lenders became much more cautious about issuing loans. Lenders also were feeling the pinch from bearing the costs of maintaining and selling houses on which they had foreclosed. Some started going out of business.

The effects of foreclosure “reach far beyond a single house on a single block,” states the Pew report. “Homeowners are estimated to lose $356 billion in home value because of nearby foreclosures, affecting nearly 40 million homes. The foreclosure problem also has spread to homeowners with prime loans—borrowers with solid credit histories. With home prices falling and credit tightening, prime borrowers are facing the same financial stress as those with subprime credit.”

GETTING BACK ON DEFENSE

Some practitioners say that for many homeowners, foreclosure is a form of surrender.

“Few people contest foreclosure,” says Robert C. Hill Jr., a sole practitioner in Fort Myers, Fla., who often represents mortgage lenders. “Only about 5 to 10 percent of borrowers show up, and they just tell the judge their tales of woe,” says Hill. “Some of those tales are very sad, but there’s nothing the judge can do.”

Yet the legal tide that has long favored lenders in foreclosure actions may be turning.

First and foremost, homeowners facing foreclosure actions should seek legal help, says Alan M. White, a professor at Valparaiso University School of Law in Indiana. “It is a shame to see people just walking away from their homes when there is a reasonable solution,” says White, who teaches consumer law. “There are still a lot of preventable foreclosures going on, and they would be stopped if more people sought legal counsel.”

Representing a homeowner who has defaulted on a mortgage is no easy task. The lawyer often must wade through a morass of loan documents, real estate pooling agreements, securitization documents, loan servicing agreements and other papers in order to determine who owes what to whom—and what each party’s legal obligations are. The lawyer must be familiar with mortgage foreclosure law, debt collection law, bankruptcy law and consumer protection law.

“It is a complicated practice,” says Charney.

Nevertheless, courts dealing with growing foreclosure caseloads have become more receptive to challenges to foreclosure actions. Timeworn defenses have gained new teeth while new tactics for resisting foreclosures are winning acceptance from courts. (In jurisdictions that permit nonjudicial foreclosures, homeowners must seek court orders enjoining them.)

Illustration by Stuart Bradford

“Increasingly, financial institutions are concerned that what used to be a traditional cookie-cutter foreclosure isn’t anymore,” says Traci H. Rollins, a partner in the West Palm Beach, Fla., office of Squire, Sanders & Dempsey who represents lenders. “Sometimes borrowers’ attorneys are raising new defenses. Sometimes they are raising the same defenses as before, but the courts are treating them differently.”

Rollins also sees judges having a more skeptical attitude toward lenders, which she attributes at least partly to widespread allegations of fraud in the financial industry. According to news reports, the FBI and the Internal Revenue Service formed a task force in January to investigate how subprime loans were handled by the mortgage industry and how those loans were bundled into securities.

“Courts are coming into cases with the expectation that perhaps the bank has done something wrong,” Rollins says. “If the borrower alleges predatory lending, the courts look at the case even more closely. And if the bank is labeled as a subprime lender, that’s like wearing a scarlet letter. It is presumed the bank has done something wrong.”

The result is that courts often will stop a foreclosure for even a tiny error in granting, servicing or foreclosing on the loan, Rollins says. “Alleged hyper-technical violations that courts wouldn’t countenance [a few years ago] are now being looked at more seriously because of the environment where it is believed that a lot of banks have done a lot of wrong things,” she says.

So now, a minor violation of the federal Truth in Lending Act—say, listing on the wrong line the fee for delivering closing documents by Express Mail—may have dire consequences for a foreclosure petition because courts are showing more willingness to use that kind of technical violation as grounds for dismissal.

“If the borrower received one copy of the disclosure statement instead of two copies, that would not have been taken seriously by the courts in the past,” says Rollins. “Now it is.”

If the court finds that the statute was violated, the borrower may rescind the loan, which would defeat the lender’s attempt to foreclose. All the borrower’s loan payments must be credited back to principal, and the borrower can then seek refinancing for the remaining principal. In addition, the borrower may obtain attorney fees and either actual damages or statutory damages of $2,000.

The courts also are taking a tougher stand on violations of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act and the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act, which mandates that borrowers must receive detailed information about the costs of obtaining a mortgage loan and closing on the purchase of a house.

In addition, 36 states—including California, Florida, Illinois, Michigan, Nevada and New York—have enacted statutes targeting subprime and predatory lending.

“They kick in if interest rates and/or points and fees exceed a certain level,” says White. “They regulate certain loan agreement provisions. Some require additional disclosures [to borrowers]. Some require borrowers to receive credit counseling prior to any foreclosure action. Typical remedies include damages or rescission.”

Then there are equitable defenses.

“These are nontraditional, make-it-up-as-you-go equitable causes of action,” Rollins says. They make the argument that, since foreclosure is an equitable remedy, it should be denied to a plaintiff who has not pursued the claim in the spirit of fairness and right-dealing that is integral to equity principles.

“You are seeing more and more allegations that a bank targeted a group of people who had lower incomes and didn’t have a lot of education, or targeted immigrants who were less sophisticated about lending, and gave loans the bank knew weren’t suitable for them,” says Rollins.

Lawyers who represent borrowers say courts are becoming more receptive to equitable defenses. Rollins cites a case in which she is representing the plaintiff in a foreclosure. The borrower, says Rollins, “was recently able to survive dismissal of her claim for ‘wrongful failure to verify employment.’ She claimed that the lender, had it conducted due diligence, would have learned that she was not employed at the income level she indicated. The court was unaffected by the fact that she swore to her employment status under oath. Instead, the court held that this may be a viable defense to enforcement/foreclosure of her mortgage loan.”

Counsel for borrowers also have asserted, as an equitable defense, that plaintiffs failed to notify delinquent borrowers of their right to loan counseling under the National Housing Act.

TURNING THE TABLES

A recent court ruling has opened the way for attorneys to use one of the key mechanisms that created the mortgage lending mess as a weapon to help borrowers fight back against foreclosure actions.

On Oct. 31, 2007, Judge Christopher A. Boyko of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio dismissed 14 separate foreclosure complaints because the plaintiffs failed to produce documentation confirming that they were the holders and owners of the mortgages on which they were seeking to foreclose.

In each case, Boyko noted, documents identified the original lending institutions, not the entities that later acquired the loans and were now seeking to foreclose, as the mortgagees. Moreover, the plaintiffs failed to produce documents showing that the loans were assigned to them.

Holding that the plaintiffs failed to establish federal court jurisdiction under Article III of the Constitution, Boyko dismissed their petitions. “This court acknowledges the right of banks, holding valid mortgages, to receive timely payments,” wrote Boyko in his order in In re Foreclosure Cases. “And, if they do not receive timely payments, banks have the right to properly file actions on the defaulted notes—seeking foreclosure on the property securing the notes. Yet, this court possesses the independent obligations to preserve the judicial integrity of the federal court and to jealously guard federal jurisdiction. Neither the fluidity of the secondary market, nor monetary or economic considerations of the parties, nor the convenience of the litigants supersede those obligations.”

Since Boyko’s ruling, more than 100 foreclosure actions have been dismissed in federal courts and some state courts because plaintiffs couldn’t prove they owned the mortgages on which they were seeking to foreclose. Lawyers say the ruling also has spawned some borrower class-action suits.

In the old days, when a mortgage created a long-term relationship between borrower and lender, it was easy for the lender to prove its interest in the loan. The bank that issued the loan would just produce the note, which it still held.

Securitization, however, changed all that.

In the late 1980s, banks started selling their home loans to other financial entities, which “pooled” large numbers of loans, put them into trusts and sold securities based on them. Purchasers of these collateralized debt obligations received regular payments on their investments as borrowers repaid their loans.

That meant loan originators no longer needed to wait years to get returns from their mortgages. Instead, they could sell the loans and make a quick profit. But loan originators also lost their incentive to ensure that borrowers could repay the loans. A default would be someone else’s concern.

Another consequence of securitization is that, because loan originators seldom hold mortgages anymore, a borrower who runs into trouble with mortgage payments is going to find it hard to identify someone in the chain of financial institutions who might be willing to help resolve the problem.

The originating lender has probably sold the loan, so it’s out of the picture. And it is extremely difficult to identify the new holder of the mortgage. That leaves the loan servicer, the company to which the borrower sends monthly mortgage payments.

But loan servicers haven’t seemed particularly interested in helping struggling borrowers—perhaps because they have a strong financial incentive to push loans into default.

Servicers typically are paid 25 basis points for servicing performing loans, but double that for servicing loans in default. The fee for servicing a loan with a $100,000 balance, for instance, is $250, but if the loan goes into default that fee would go up to $500. Moreover, once a loan goes into default, servicers can charge late fees, inspection fees and a variety of other fees.

“A $50 charge here, an $80 charge there may not seem like much individually, but it is a lot more than the servicer would get per month from a performing loan,” says O. Max Gardner III, a sole practitioner in Shelby, N.C., who concentrates in consumer bankruptcy law.

The consequence of this system is that entities involved in originating and securitizing loans frequently did not comply with the formalities of assigning the notes and physically transferring them. And now, trying to create a paper trail involves significant time and expense—if it’s possible at all. Judge Boyko’s ruling showed that such a dysfunctional system will likely come back to haunt the lending industry.

“You have to prove to the court that you have the original note and that you have lawfully obtained it via an unbroken chain of assignments,” Gardner says. “Those have turned out to be two very difficult obstacles for trustees to establish. Over 400 loan originators went out of business last year. I don’t see how you get an assignment from somebody that went out of business.”

PUTTING THE HEAT ON LENDERS

Bankruptcy provides another refuge for homeowners seeking to avoid foreclosure.

While the typical home mortgage can’t be wiped out in bankruptcy, filing for bankruptcy can help a defaulting borrower in other important ways.

Illustration by Stuart Bradford

A distressed borrower can obtain some relief in Chapter 13 bankruptcy proceedings, which allow debts to be rescheduled, because foreclosure actions are stayed while bankruptcy proceedings unfold. Bankruptcy court also gives the borrower a forum in which to assert claims against the lender and servicer.

And the bankruptcy court may stretch out the payment schedule on any big balloon payment that comes due while a repayment plan is in effect. The bankruptcy court also may “cram down”(reduce the balance) or wipe out a second mortgage on an owner-occupied residence, as long as the value of the mortgaged property is less than the value of the first mortgage.

Moreover, a borrower filing a Chapter 13 bankruptcy may be given up to three years in which to make up payments that he or she missed before filing the bankruptcy petition. There’s a catch, however. The debtor must keep current on all future mortgage payments. Failure to meet just one future payment is enough to throw the debtor out of Chapter 13 protection.

At least one case suggests that actions by lenders sometimes make it harder for debtors to meet their repayment obligations.

In 2007, Judge Elizabeth W. Magner, a federal bankruptcy judge in the Eastern District of Louisiana, voiced concerns about that problem in Jones v. Wells Fargo Home Mortgage (In re Jones). Other bankruptcy judges have echoed those concerns.

“In this court’s experience,” wrote Magner in her opinion, “few, if any, lenders make the adjustments necessary to properly account for a reorganized debt repayment plan. As a result, it is common to see late charges, fees and other expenses assessed to a debtor’s loan as a result of post-petition accounting mistakes made by lenders. It appears to this court that lenders refuse to make these adjustments because [in part] few debtors challenge their accounting.”

Judge Magner determined that the lender, Wells Fargo, had overcharged the borrower by 12 percent of his total amount due and ordered the bank to repay him the overcharge—$24,450.65—with interest. In a subsequent proceeding, Magner ordered Wells Fargo to pay the debtor’s attorney fees of $67,202.45, and the company escaped punitive sanctions only by agreeing to revise its general accounting procedures for debtors with pending bankruptcy cases.

Recent research by professor Katherine M. Porter of the University of Iowa College of Law in Iowa City supports what Magner and other judges are finding. In her study of 1,733 bankruptcy petitions filed in April 2006, Porter determined that more than half of them contained questionable fees.

Ultimately, homeowners in fear of foreclosure may find Congress to be their greatest ally.

WILL THE CAVALRY ARRIVE IN TIME?

By late May, Congress was getting closer to passing legislation aimed primarily at helping embattled borrowers replace loans carrying escalating monthly payments with more affordable ones underwritten by entities backed by the federal government. The American Housing Rescue and Foreclosure Prevention Act passed the House of Representatives on May 8. The Federal Housing Finance Regulatory Reform Act was endorsed overwhelmingly by the Senate Banking Committee on May 20. The Senate bill also would impose greater controls on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, private corporations created by Congress to help finance the mortgage market.

The administration has not indicated whether President Bush would veto this legislation. Some opponents have complained that intervention by the federal government would amount to a bailout for borrowers who made risky financing decisions and undercut valid contractual agreements.

But in a speech on May 5, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said, “High rates of delinquency and foreclosure can have substantial spillover effects on the housing market, the financial markets and the broader economy. Therefore, doing what we can to avoid preventable foreclosures is not just in the interest of lenders and borrowers. It’s in everybody’s interest.”

More from the ABA Journal:

“Unconventional Wisdom,” June 2005 ABA Journal

“Strange New World,” January 2007 ABA Journal

“Mortgage Fraud Mess,” July 2007 ABA Journal

“Finding It Hard to Be a Loan,” March 2008 ABA Journal