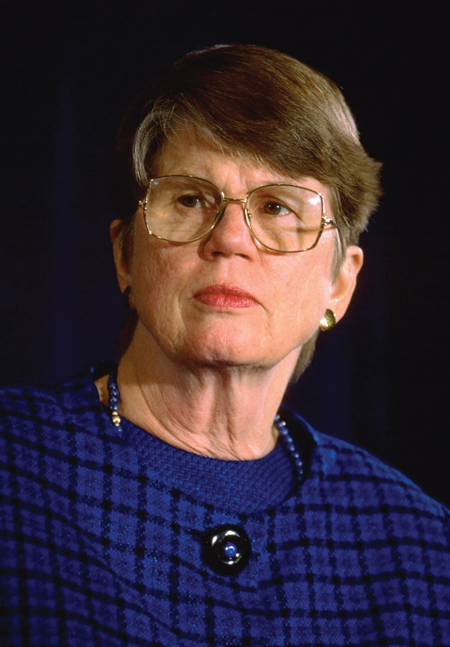

Farewell to a Friend: Janet Reno worked closely with the ABA

Janet Reno. Getty Images.

Janet Reno’s death in November was felt acutely in the ranks of the American Bar Association. Several ABA leaders described Reno, who worked as U.S. attorney general from 1993 to 2001, as a great friend of the association. In many ways, the feeling was mutual.

Reno, who died at age 78 after a lengthy battle with Parkinson’s disease, “was a groundbreaker and a giant in the legal community,” said ABA President Linda A. Klein of Atlanta in a condolence statement. “She was a longtime member and friend of the ABA, serving on several important commissions and task forces that worked to improve the legal system.”

Reno also gave a number of speeches to various ABA groups before, during and after her term as attorney general, Klein said, and she received several awards from the association.

Reno worked on the ABA’s Commission on Standards and Juvenile Justice in 1973, the Special Committee on Criminal Justice in a Free Society from 1986 to 1988, and the Task Force on Minorities and the Justice System in 1992. She was honored with a special ABA award at the Margaret Brent dinner in 1993, received the ABA’s D’Alemberte Raven Award for outstanding service in dispute resolution in 1997, and the 2009 Thurgood Marshall Award from the Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities (now the Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice).

A children’s advocate

Reno was particularly simpatico with the ABA on the legal rights of children. “Ms. Reno always fought for the rights of children in the legal system, pushing for juvenile justice reform and advocating programs to assist troubled youths, directing them away from crime rather than incarcerating them,” Klein said. “She was a tenacious prosecutor of cases involving child abuse, delinquent child support and domestic violence, while also introducing innovations in drug courts.”

Reno’s concerns about children’s issues were reflected in the importance she gave to reforms within the Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, says Howard Davidson, the founding director (now retired) of the ABA Center on Children and the Law, who met with her in connection with the release of the ABA’s 1993 report America’s Children at Risk: A National Agenda for Legal Action.

But Reno was no pushover on criminal justice issues. “She was a dogged prosecutor who believed equally in the conviction of the guilty but also the protection for the innocent with strict adherence to the rule of law,” Klein said.

A native of Miami, Reno struck up friendships with two distinguished ABA members from Florida even before President Bill Clinton appointed her to become the first woman to work as attorney general. Former ABA President Talbot “Sandy” D’Alemberte got to know Reno when she was staff director of the judiciary committee in the Florida House of Representatives and he was serving in the legislature. Later, D’Alemberte says, she was his trial partner in several cases when they were in private practice.

“We were wonderful colleagues, and she was a damn good lawyer,” says D’Alemberte, who is president emeritus of Florida State University in Tallahassee and a law professor there. He was president of the ABA from 1991 to 1992.

Neal R. Sonnett of Miami recalls introducing Reno at a 1993 luncheon of the ABA’s Criminal Justice Section, which he chaired at the time and still represents in the ABA House of Delegates.

“All of us who believe in the administration of justice, who believe that the justice system is on a fast track to collapse and needs desperately to be improved, who believe in fairness and the Bill of Rights and constitutional liberties, in effective but fair law enforcement and prosecution, are as happy as any human beings could be that she serves us as the attorney general of the United States,” Sonnett said in his introduction at the luncheon.

Roberta Cooper Ramo, a shareholder at Modrall Sperling in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who became the ABA’s first female president in 1995, shared a “first woman” affinity with Reno. “It was so important for us to have as the first woman attorney general a person of great integrity,” Ramo says.

Martha W. Barnett, a partner at Holland & Knight in Tallahassee who was ABA president from 2000 to 2001, also met Reno in Florida’s capital city. “You couldn’t miss her,” Barnett says, noting that Reno was a tall, distinctive woman who stood out in a crowd. “There was both a seriousness and a warmth about her,” Barnett says, and there was “not an arrogant bone in her body.”

Barnett describes Reno as a “servant leader.” Reno felt particularly at home at the ABA, Barnett says, because she “believed in institutions and understood the power of them to do good, to be a voice in a forum for consensus building. And the ABA can be a powerful force for good.”

NO ‘CREATURE OF WASHINGTON’

Reno’s legacy “is very, very broad and deep,” says Jamie Gorelick, a partner at Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr who’s based in Washington, D.C., and worked as Reno’s deputy attorney general, the second-highest position in the DOJ. Reno “very much respected the ABA and would respond to every request for meetings or interaction, some where we were entirely aligned and some where we were not,” Gorelick says. Reno “was not a creature of Washington, and I was,” Gorelick says, so the attorney general was freed up “to do the things she wanted,” including visiting with and learning from people and groups across the country. Gorelick would help Reno facilitate her decision-making when she returned to Washington with new ideas and projects.

Gorelick says Reno brought the experience and views “of someone who has to deliver justice on the ground” to the DOJ and spent much time thinking about how the federal government could deliver that justice. “She saw and used justice in America very holistically, in a way no attorney general has,” Gorelick adds.

Holding a view that resonates today, Reno knew how important it is for law enforcement to have the trust of communities, Gorelick says. And she knew a prosecutor could not be effective in addressing violent crimes unless people trusted that law enforcement officials would be in the community.

She thought about what resources prosecutors needed to let them talk with communities, Gorelick says, including training programs with best practices, funding for local police, and oversight of the Community Oriented Policing Services program, one of Clinton’s priorities to put 100,000 additional police officers on America’s streets to help fight crime. That program was “well before its time, although she would say it was well after its time,” Gorelick says. (There has been debate in recent years over the effectiveness of the COPS program.)

Robert A. Stein, who was ABA executive director from 1994 to 2006, says Reno “was ahead of her time in thinking about issues that continue to be current legal challenges.” Stein, a professor and former dean at the University of Minnesota Law School in Minneapolis, recalls talking with her about how to maintain a fair, equitable immigration program and hearing her invite a conversation about issues that relate to cybercrime.

For her part, Reno often praised the ABA and its lawyers, asking them continually to contribute their unique talents to make the country a better place. Perhaps her feelings toward the ABA could be summed up in a remark she made during a speech at the association’s 1998 annual meeting: “I am so proud to be a lawyer in the United States, and I am so proud to be a member of this association. ... I salute you all.” It was a salute that was returned many times.

This article originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of the