'Just Mercy' author Bryan Stevenson tells stories to change the world

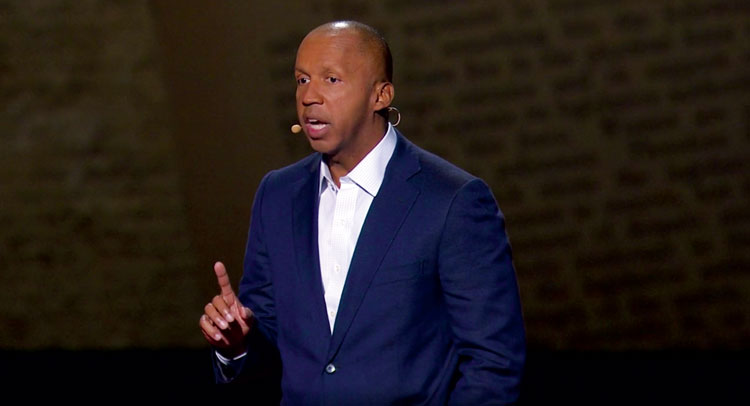

Photograph of Bryan Stevenson courtesy of TED.com.

More than 40 years ago, short story writer and novelist John Cheever said to his creative writing classes that he told stories because it is easier to change the shape of the world than it is to change one person’s mind. I was a student in his class, and the line stuck with me. Cheever was a brilliant and insightful teacher imbued with a belief in the transformative power of storytelling. But, at that time, I didn’t understand what he meant. Today, I have a better understanding of what he was getting at. Curiously, I have learned about the power of storytelling through the practice and teaching of the law.

Civil rights attorney, writer and law professor Bryan Stevenson intuitively comprehends Cheever’s wisdom. Whether at trial or in an appellate courtroom, writing his own superb autobiographical nonfiction, the best-selling Just Mercy, or in his efforts to evoke and acknowledge the historical narratives of the black experience and our legacy of racial injustice in America through the work of the Equal Justice Initiative, Stevenson employs well-told stories to change the shape of the world.

Of course, Cheever wrote fictional narratives to reveal hidden dimensions of the social landscape of privileged upper classes in America during the 20th century. Stevenson, on the other hand, tells factually accurate and legally meticulous stories. But Stevenson’s stories reveal an equally hidden shadow world inhabited by the poor and disempowered within our society, who are often trapped within our criminal justice system. Both storytellers reveal discrepancies between how we act as a society, contrasted with idealizations of who we are and how we imagine ourselves to be.

In very different ways, both Cheever and Stevenson are prophetic artists and teachers, telling “truthful” stories of a different sort because, often, it is easier to change the shape of the world than it is to change one person’s mind.

CIVIL RIGHTS AND THE PUBLIC IMAGINATION

Stevenson is an updated, 21st-century model of the civil rights attorney as a transformational storyteller. His roots hark back to the great civil rights litigation attorneys of earlier generations: from Charles Hamilton Houston to Thurgood Marshall to Jack Greenberg to Julius Chambers and on to Anthony Amsterdam. These mythic litigators went from courtroom to courtroom arguing trial and appellate cases, interpreting the meaning of our Constitution, arguing for social justice, executing planned socially transformative litigation strategies. And yes, like Stevenson, all sought to be prophetic storytellers, calling on people to be true to whom they are supposed to be and what they might become.

Earlier planned litigation strategies (such as campaigns for school desegregation and for the abolition of capital punishment) took place primarily within the court system, employing legal argumentation as the mechanism for social change. Much of Stevenson’s practice takes place within the courtroom of the public imagination, via the amplifications of media. Stevenson understands that, in our particular time, stories that capture the popular imagination and gain cultural traction profoundly influence the law and may affect outcomes in specific legal cases.

I urge readers to watch Stevenson’s superb 23-minute TED Talk: “We Need to Talk About an Injustice.” Stevenson explores complex and controversial themes, such as exploitation and racism in our history and systemic injustice within our current-day criminal justice system. Yet his presentation captures the imagination of his privileged audience without pandering to it. Stevenson never lectures or argues at the audience. But he never softens his own beliefs, never turns his heartfelt passion into mush. His performance is pitch-perfect and provides an eloquent model of how a gifted litigation attorney employs storytelling skills to empower an audience with a meticulous lawyerlike argument.

TALKING POINTS

Stevenson’s TED Talk has been analyzed in several recent books. It is used as a model for opening statements in Shane Read’s Turning Points at Trial. And it is analyzed as a prototype of effective salesmanship in Carmine Gallo’s The Storyteller’s Secret. Why are Gallo’s observations on sales “pitches” relevant for lawyers? Obviously, because litigation lawyers are also salespeople of a sort, trying to move our audiences to action and to close our deals with favorable verdicts and outcomes.

There are many lessons for lawyers in Stevenson’s performance. First, there is the stylistic quality of his “voice.” Stevenson is understated, self-effacing, yet passionately engaged with his material. He speaks without notes and appears psychologically naked; there is nothing between him and his audience. He seems as if he is in a dialogue with his audience.

In a lawyerlike way, Stevenson also strategically employs compelling statistics and information to make his argument. He realizes that less is more and distills supporting materials. For example, illustrating the severity of our criminal punishments and our practice of mass incarceration, he says: “Well, I’ve been trying to say something about our criminal justice system. This country is very different today than it was 40 years ago. In 1972, there were 300,000 people in jails and prisons. Today, there are 2.3 million. The United States now has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. We have 7 million people on probation and parole.”

Revealing systemic errors in guilty verdicts in capital cases, he declares: “The death penalty in America is defined by error. For every nine people who’ve been executed, we’ve actually identified one innocent person who’s been exonerated and released from death row.” He continues by arguing that race is often determinant of sentencing, especially in death penalty cases in some states where “you’re 11 times more likely to get the death penalty if the victim is white than if the victim is black; 22 more likely to get it if the defendant is black and the victim is white.”

But Stevenson’s presentation is never pedantic; just the opposite. It is compelling and entertaining, punctuated by the audience’s laughter. His presentation is filled with well-placed notes of hope, suggesting the possibility of redemption—both for his clients and for us all.

How does Stevenson achieve this result? He builds upon a secular version of a biblical theme forged for the TED Talk audience: We are all interconnected. And “we will ultimately not be judged by our technology,” “our design,” “our intellect” or “our reason.”

“Ultimately,” he says, “you judge the character of a society not by how they treat the rich and the powerful and the privileged but how they treat the poor, the condemned, the incarcerated. Because it’s in that nexus that we actually begin to understand truly profound things about who we are.” Stevenson is not just talking about correcting injustice here; he is talking about the redemptive power of forgiveness, compassion and mercy.

How does Stevenson expose the flaws in the criminal justice system while simultaneously calling forth the better angels of his audience, compressing all of his material into less than 30 minutes? He uses stories, of course.

THE 3 WISE TALES

Bryan Stevenson: “The United States now has the highest rate of incarceration in the world.” Photograph courtesy of TED.com

“We Need to Talk About an Injustice” employs the spine of three carefully selected autobiographical ministories. These stories are akin to secular parables—teaching stories. Each episode features Stevenson as the primary character who learns a vital life lesson from a wiser and older person. Each story is imbued with gentle humor and irony, and each is beautifully delivered. Stevenson receives wisdom and is transformed, and the audience goes along with him.

The first story is about Stevenson as a young boy who learns from his grandmother about the transformative power of love to shape identity and provide the resolve that defines the arc of his professional life.

The second story is a lesson about the nature of struggle, commitment and community that Stevenson learns from Rosa Parks and two elderly civil rights leaders over a lunch in Atlanta. The third is about integrity and resistance, and the long arc of the struggle against oppression—wisdom Stevenson receives from an elderly court janitor when he argues a motion titled: “Motion to try my poor, 14-year-old, black, male client like a privileged, white, 75-year-old corporate executive.” The privileged TED Talk audience laughs heartily and stays with him throughout; he has them in the palm of his hand.

My own takeaway from Stevenson’s masterful performance is that we can twine diverse strands into a persuasive argument that appeals to our better natures when, like Stevenson, we are willing to take risks, employ stories, use humor purposefully and practice to perfection our storytelling deliveries.

And, oh yes, also when we learn to trust and follow the guidance of our own courageous and imaginative hearts in the service of forces that are sometimes much larger and more powerful than we are.

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of Storytelling for Lawyers.

This article was published in the May 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Story Power: Attorney Bryan Stevenson tells stories to change the shape of the world".