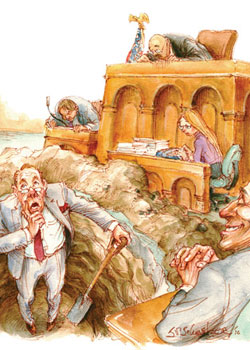

Keeping Out of a Hole: It’s a Lot Easier to Avoid Problems Than to Fix Them

Illustration by John Schmelzer

The bar association’s Wednesday night litigation program was packed to the gills. It was scheduled to start at 8, and by 7:30 there was standing room only in the Great Hall of the bar headquarters. Two adjacent rooms with closed-circuit television hookups absorbed the overflow.

Apparently the program topic really struck a chord. The subject was holes: how to avoid them in your case and how to dig yourself out if you do fall into one.

To no one’s surprise, the speakers had plenty to talk about.

THE FORGETFUL CLIENT

Sandra Garcia, the personal injury lawyer, opened the program by acting out a scenario with the help of a small “cast.” Sandra was sitting at a table facing the audience when her assistant came from offstage and said, “Your client in the employment case is here to see you, Ms. Garcia. Shall I show him in?”

“Please,” said Sandra, who stood up as her assistant showed the “client”—actually Marcus Allen, another attorney in town—into her “office.”

“Mr. Allen, it’s good to see you again,” said Sandra.

“Thanks,” said Marcus. “Frankly, I’m a little worried about this lawyer on the other side who’s going to be taking my disposition.”

“Of course,” said Sandra. “It’s natural to worry about important things that you’ve never done before. But don’t worry. You’ll do just fine.

“And by the way, it’s called a deposition. Under oath, you’ll answer the other lawyer’s questions, and your answers will be recorded by a court reporter. ‘Disposition’ is how you feel.” A ripple of laughter ran through the room.

“Yeah, well,” said Marcus Allen, “I don’t feel too good about this business anyway. I was talking to my cousin about this disposition stuff, and she says there is no law that says you have to remember everything just because you raise your hand and swear to tell the truth.”

That’s when federal district Judge Horatio Standwell stood up and asked the audience, “How should Sandy Garcia respond to what her client said?”

Bill Pidcoe, who was sitting in the third row, said, “As far as I’m concerned, that’s the red-eyed law. There’s no rule I know of that says it’s illegal for a witness to forget something.”

“True,” said Angie Sandler, “but putting it that way creates the impression that the lawyer is telling her client that if he doesn’t like the honest answer to a question, all he has to do is say he doesn’t remember.”

“Exactly,” said Ernie Romero, “which some people think flunks the professional ethics quiz.”

“So let me put the question in the context of this situation,” said Judge Standwell. “How many feel it would be improper for Sandra Garcia to tell her client there is no rule that says it’s illegal for a party to a lawsuit to forget something that hurts his case?”

About two-thirds of the lawyers raised their hands.

“And how many feel there would be nothing improper in saying that?”

Only a few hands went up.

“That’s something to take with you as we go on,” said Judge Standwell. “One of the best ways to dig yourself out of a hole is to avoid getting into it in the first place.”

IS THE STORY GETTING BETTER—OR WORSE?

Mike Torrent, the corporate trial lawyer—he says “corporate litigators” don’t actually try cases—presented the next scenario.

“Flexo-Pic, the manufacturer of a new foldable, flexible plastic video screen—no thicker than three pieces of typing paper—says it got a big order from Micro-Com, the designer of an ultrathin telephone-camera-calculator-printer that’s the size of a credit card.

“The CEOs of these two companies initially met face to face in the Micro-Chip Bar and Grille to discuss an important sale,” said Mike. “The head of Flexo-Pic tells you that he and the head of Micro-Com shook hands on a deal for Flexo-Pic to sell thousands of square feet of its flexible video screen to go on Micro-Com’s electronic gizmos.

“As is customary in the industry, there was nothing in writing except a handwritten note from the CEO of Flexo-Pic saying ‘Thanks for the order, Mark.’

“Flexo-Pic immediately doubled production of its plastic video screen material, and six weeks later it started delivering $24 million worth of video screens to Micro-Com.

“Micro-Com promptly shipped them all back to Flexo-Pic, saying it had never ordered anything from the company.

“So Flexo-Pic asks you to represent the company in this dispute.”

Then Mike looked at all the lawyers in the audience and said, “What’s the first thing you do?”

“See if you can find anything that backs up Micro-Com’s story,” said Jamie Torrez.

“Excellent,” said Mike. “Where do you go and what do you do?”

“Run a background check on Flexo-Pic and its CEO,” said Jamie.

“Go visit the Flexo-Pic company and see its operation,” said Ernie Romero. “Do they really have a lot of excess video screen material lying around?”

“Do a background check on Micro-Com,” said Frank Logan.

“OK, so you do all that and you’re convinced Flexo-Pic really thought it had a deal,” said Mike. “Then what?”

“We need more witnesses,” said Beth Golden. “Like was there anyone else at the Micro-Chip Bar & Grille who could verify that these two CEOs met and discussed anything?”

“And you need to find out what’s been happening to Micro-Com’s business,” said Frank Logan. “They might not be worth pursuing.”

“Right,” said Maria Archuleta. “But Flexo-Pic may need to bring a lawsuit because it can’t sell its thin plastic sheets to any other customers.”

“Excellent,” said Mike Torrent.

SEVEN WAYS TO MAKE A LOSING ARGUMENT

It was Angus’ turn to lead the discussion. “there are lots of different ways to make a losing argument,” he said. “And the first is the most surprising: Argue with the judge.

“Wait, you say. From the first day of law school and right into practice, we’ve been told that argument is what the law is all about.

“OK, but argue to the judge—not with the judge.

“Here are some more keys to a losing argument,” said Angus.

• “Bury your argument in clutter. Whether you’re arguing facts or law—or a combination of the two—think it through and keep it simple.

• “Misstate the facts. Be simple, be careful, be direct. Never exaggerate any fact.

• “Base your argument on obscure technicalities. Leave the arcane oddities to the academics. Good arguments are easy for anyone to understand.

• “Read your argument to the jury. You want to be simple, direct and command instant comprehension. Unless you’re a professional actor, you lose all that when you read.

• “Push a good point too far. There are limits to every good point. Stop while you’re ahead.

• “Give in to sudden inspiration. If it didn’t come to you before you started to speak, you didn’t have a chance to think it through. If you don’t fall into a hole, you won’t have to dig yourself out.”

Jim McElhaney is the Baker and Hostetler Distinguished Scholar in Trial Practice at Case Western Reserve University School of Law in Cleveland and the Joseph C. Hutcheson Distinguished Lecturer in Trial Advocacy at South Texas College of Law in Houston.