The legal tech market is soaring, and nowhere is this more apparent than Y Combinator

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

As Jake Heller, CEO of Casetext, waited his turn to interview at Silicon Valley’s prestigious accelerator, Y Combinator, he witnessed quite a scene. Some of the founders were leaving the notoriously stressful interview in tears.

“It was havoc and chaos,” he recalls.

At that moment in 2013, Casetext wasn’t even Casetext—it was Law Commons. It was a proof of concept without a single customer. He describes the application as a “total long shot.”

In the allotted 10 minutes, he and his co-founder answered rapid-fire questions from YC’s partners on why they should receive the money, support and network that comes with joining one of the accelerator’s two annual classes.

A little later on, as he boarded an airplane headed to Chicago, he got the call: They’d been accepted. As he remembers, he leaped out of his seat, attracting the attention of the flight attendants, who asked him to fasten his seat belt.

Five years later, Heller says he thinks about his YC experience almost every day. It taught him how to run a business, be a manager, and it helped the company raise capital. “It was a really formative experience.”

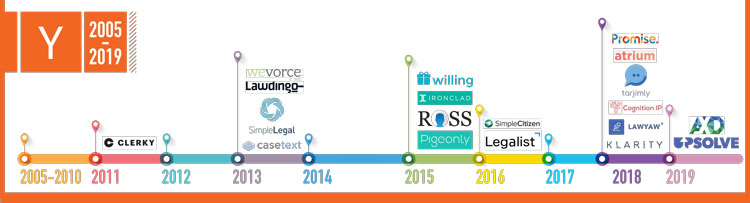

Casetext is one of 19 legal tech organizations that have been accepted to YC, according to original analysis by the ABA Journal and confirmed by YC. While the accelerator has been around since 2005, eight for-profit and nonprofit legal tech organizations have taken part since 2018. Some hope the increased matriculation is a sign of a maturing legal technology sector, while others think it’s mere happenstance.

Accelerators possess a specific role in the startup ecosystem, explains Dana Thompson, director of the entrepreneurship clinic at the University of Michigan Law School. Focused on early-stage companies, acceptance into an accelerator means receiving “concentrated advice and focus on their business model in a way that many other startups don’t get,” she says.

In the case of YC, a company trades 7 percent of its equity to the accelerator in exchange for $150,000 and support honing an early-stage business plan and product.

Chart by Sara Wadford

Having made early bets on companies such as Airbnb, Dropbox and Reddit, YC’s reputation leads many to see it as a bellwether for the tech sector.

“YC gives pretty strong signals when they believe an industry is changing,” says Tucker Cottingham, CEO of document automation company Lawyaw, which went through YC in 2018. “It was made pretty clear to us that they see the legal industry as undergoing a big change, and that technology is going to be a really big part of the future of how lawyers practice law.”

Other YC alumni include Atrium LTS (2018), Ironclad (2015), Ross Intelligence (2015) and Wevorce (2013).

The accelerator is also paying attention to the access-to-justice gap by supporting nonprofits like Upsolve (2019), which helps people file Chapter 7 bankruptcy; Promise (2018), a platform to improve criminal justice systems; and Tarjimly (2018), a translation service for refugees.

“They want to help support initiatives that are bringing people out of poverty at scale using technology,” says Jonathan Petts, executive director of Upsolve.

While it’s not possible to take equity in a nonprofit, YC charitably offers grant funding and the same rigorous support provided to the for-profit participants, like helping an organization better connect with people in need of their service.

Even with an uptick in legal tech organizations at YC, they are only slightly more than 1 percent of all accepted companies, according to the Journal’s analysis.

Jonathan Levy, a partner at YC, says the accelerator doesn’t have a specific interest in legal tech—or any industry for that matter.

“The uptick in admissions is more likely the result of an uptick of legal tech startups, or just a coincidence,” Levy says. “We have different companies in different parts of the legal tech market and think most of them have great opportunities to disrupt an opaque industry.”

More legal technology companies at YC is a sign that the sector is maturing, says Jules Miller, a partner at Prose Ventures, a fund focused on legal and compliance tech based in New York City. “It’s a function of there being better companies,” she says.

Numerous data points indicate that legal tech is coming into its own.

There was a surge in investments in legal tech companies—from $233 million in 2017 to $1.6 billion in 2018 (albeit about one-third was raised by LegalZoom), according to Forbes. Megafirms such as Dentons and Foley & Lardner both have venture funds. In February, Axiom, an alternative legal services provider, began the application process to go public. It follows DocuSign, which went public last year, raising $629 million in an April 2018 IPO.

Some of the YC grads aspire to join the legal tech pantheon of publicly traded companies one day. In the meantime, many of the founders told the Journal that their time at YC built a deep network that continues to pay dividends by providing help and insight as their companies grow.

“It helps us avoid major detours into somewhere we shouldn’t be going,” says Ray Mina, Lawyaw’s head of growth and marketing. “That is priceless.”

This article was published in the May 2019 ABA Journal magazine with the title "Business Is Booming."