Legal ed section takes a pass on changing tenure provision in accreditation standards

Professor Kingsfield (The Paper Chase, 1973): “You come in here with a skull full of mush and … leave thinking like a lawyer.” Photo of actor John Houseman by ©Deborah Feingold/Corbis.

The future of the tenure system for law professors in the United States has been one of the more difficult issues addressed by the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar as part of a lengthy review of its accreditation standards for U.S. law schools.

But after taking one last stab at finding a formula that would give most law professors an assurance of job security without specifically requiring schools to grant them tenure, the section council decided in March to stand pat with the current language in Standard 405 of the Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools. While the standard is somewhat lacking in precision, it is widely understood to require that schools adopt some form of tenure system for their faculties.

The council is recognized by the U.S. Department of Education as the accrediting agency for programs in this country that lead to a JD degree. The council has accredited 203 institutions (four provisionally), including the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, which offers a specialized program. In its current form, Standard 405 states that a law school “shall have an established and announced policy with respect to academic freedom and tenure,” but it doesn’t spell out exactly what that policy should be or to whom it should apply. The standard also states that a school “shall afford to full-time clinical faculty members a form of security of position reasonably similar to tenure.” Interpretation 405-6 states that this requirement may be satisfied through the use of presumptively renewable long-term contracts of five years or more, but it does not preclude the use of short-term, nonrenewable contracts for legal writing instructors.

TAKE YOUR PICK

Critics of the current standard contend that it restricts management flexibility, contributes to the high cost of legal education and perpetuates what amounts to a caste system for law school faculty members. Critics also say there is no regulatory justification for an accrediting agency to dictate the terms and conditions of law school employment decisions made by schools, and they point out that tenure is not a condition for accreditation for schools in any other professional field.

But supporters of the existing standard, including nearly 650 professors who signed a letter earlier this year stating opposition to changes being considered by the section, say the elimination of tenure would jeopardize academic freedom, stifle dissenting points of view, and hamper efforts to recruit and retain minority professors.

Over the past several months, four alternative proposals to revise Standard 405 were drafted by the section’s Standards Review Committee, which submitted them to the council for consideration and possible adoption. At its March meeting in San Diego, the council debated the merits of two of the proposals, which it had posted for notice and comment. But while a clear majority of the council members expressed dissatisfaction with the current standard, neither of the two proposals garnered a consensus of support.

One of the proposed alternatives before the council would have required law schools to provide all full-time faculty members with a form of security of position “sufficient” to ensure academic freedom, and attract and retain a competent faculty. But the proposed revision would not have required that all faculty members have the same form of security of position, and it would not have specifically required tenure.

The other proposal considered by the council contained no mention of security of position. But it would have required law schools to “maintain conditions” adequate to protect academic freedom, and attract and retain a competent full-time faculty. This proposal would not require tenure, either, but would allow it to be used as a way of satisfying the standard.

RUNNING OUT OF TIME

At that point, the council briefly considered taking up a third proposal—one of two alternative approaches to the current standard that it had previously decided not to post for notice and comment. That proposal would have explicitly required tenure or a comparable form of security of position for all full-time faculty members, but it also would retain the present distinction in the types of job protections now required for clinical professors and legal writing instructors.

But the council dropped consideration of this approach because it would not be able to move it through the review and comment process quickly enough to have it reviewed by the ABA House of Delegates when it convenes in August at the association’s 2014 annual meeting in Boston. The section is committed to bringing all of its proposed accreditation-standards changes to the House at that time. The House may either concur with the section council’s proposed changes or refer them back for reconsideration up to two times, but the House may not dictate changes to the council, which has final authority over the accreditation standards.

Jeffrey E. Lewis, who chairs the Standards Review Committee, was noncommittal after the council’s action. “It’s their decision. I don’t feel it’s appropriate for me to comment,” said Lewis, a professor and dean emeritus at St. Louis University School of Law.

Meanwhile, the council approved several other revisions to the accreditation standards that had been recommended by Lewis’ committee, including an increase in the experiential learning requirement from one credit hour to at least six. At the committee’s urging, the council also let stand the existing bar pass requirement, which requires a law school to show that either 75 percent of its graduates who took the bar exam in at least three of the previous five years passed, or that its graduates’ first-time bar pass rate was no more than 15 points below the average bar pass rate for ABA-approved schools in states where its graduates took the bar.

On its own initiative, the council added language to the standards that encourages law schools to promote opportunities for students to perform at least 50 hours of pro bono service while they are in school.

The council also approved for notice and comment several other proposed changes in the standards, among them eliminating the current prohibition on students receiving academic credit for paid internships; permitting schools to admit certain students who haven’t taken the Law School Admission Test; and limiting the number of transfer credits a student may receive for prior law study unless it was undertaken as a JD-degree student at an ABA-approved school. The matters posted for notice and comment were to come back to the council for final review in June.

• Read the proposed revisions to the ABA Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools (PDF).

This article originally appeared in the June 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Dodging the T-Word: Legal ed section takes a pass on changing tenure provision in accreditation standards.”

Sidebar

Marginal uptick in jobs for recent law grads

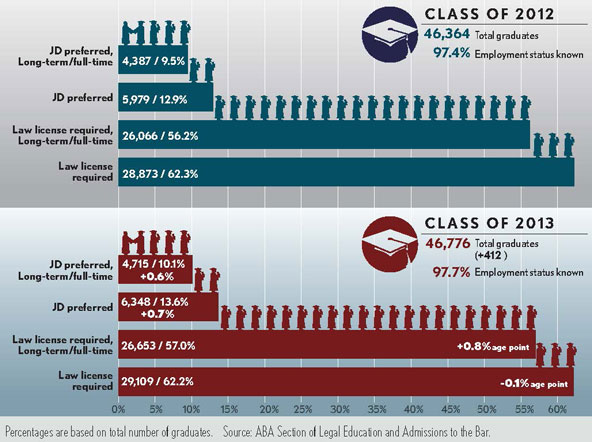

If any improvement is good news, then employment data for recent graduates of U.S. law schools accredited by the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar can be viewed as a positive trend—but just barely.

The section’s report on employment for 2013 graduates nine months after receiving their law degrees indicates that employment rose on three key measures, compared to results for the class of 2012. The data reflects the known employment status of 97.7 percent of 2013 graduates of U.S. law schools accredited by the legal ed section, compared to the known employment status of 97.4 percent of the class of 2012. Employment rates improved slightly from 2012 to 2013 for graduates in jobs for which a law degree is preferred but not required, including long-term, full-time jobs—those expected to last a year or more. The employment rate also increased slightly for graduates in jobs requiring a law license that are expected to last a year or more. But overall employment in jobs requiring a license dropped by 0.1 percentage points.

Graphics by Adam Weiskind and Brenan Sharp