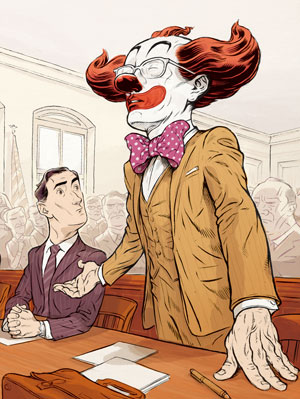

Litigation is no laughing matter to your clients

Illustration by Lars Leetaru

But for lawyers, in the serious business of helping our clients, humor is a no-no. I don't mean in your personal life. I don't mean when you're talking to a colleague. I mean in court, at depositions, in briefs—don't be funny. You'll be tempted, but don't do it.

As our U.S. Supreme Court says, in its Guide for Counsel: “Attempts at humor usually fall flat.”

Any dispute between parties that has become so rancorous that the court’s intervention is required is inherently not funny, at least to the parties. Jokes at your opponent’s expense are inflammatory. Jokes at the expense of your client are reprehensible.

You may think that no lawyer would make fun of a client in a legal setting, but you would be wrong. We don’t have to look hard for an example. There’s the case of Aaron Hernandez, the New England Patriots football star, who was convicted of murder in April. At the trial, his lawyer asked a witness on the stand if he had been trained to help the Patriots deflate footballs (a reference to the Tom Brady “Deflategate” scandal). His client was not happy—nor was the judge, who told the lawyer, in essence, to shut up. The judge admonished the lawyer to take the proceedings seriously. I would have thought a murder trial was serious enough that he would not have to be reminded.

In addition to showing bad judgment and a lack of decorum, any attempt at humor can fall flat because the judge, jury or others in the courtroom don’t have the same sense of humor you do. Worse, they could have no sense of humor at all. It’s just not worth the risk that you’ll anger or confuse someone you want to influence.

LOST IN TRANSLATION

Another problem with trying to use humor is that it won’t advance your case if no one gets it. Early in my career, I appeared for a hearing before a well-respected federal judge. The case involved a family company where the patriarch was treating the business in every way like an extension of his own household. “It’s like Louis XIV,” I said. “L’etat, c’est moi.” (In other words, “I am the state. I can do as I want.”) Everyone, not just the judge, stared at me as though I was from Mars. Clearly, I was an alien, but from France. The comment dropped with an audible thud. I didn’t try to do that again.

Then there’s the following “joke” made during a U.S. Supreme Court argument, supposedly the worst ever perpetrated by a lawyer in court. I’m not sure it was the worst, but it certainly wasn’t a good choice of words.

During the first argument in the case of Roe v. Wade (in which the court ultimately found that abortion could not be banned until the fetus was viable outside the womb) attorney Jay Floyd had the task of arguing to uphold abortion restrictions imposed by the state of Texas. Nodding to plaintiffs counsel, a woman representing the woman known as “Doe,” Floyd said: “It’s an old joke, but when a man argues against two beautiful ladies like this, they are going to have the last word.” His remark was met with silence—a silence that lasted for three seconds, which must have seemed an eternity to Floyd. He never regained his composure.

My own nomination for the worst joke is the potty humor (if you can call something not funny “humor”) of Thomas Campagne, who argued in the Supreme Court case Glickman v. Wileman Bros. & Elliott that the government should not be permitted to force companies to pay for generic advertising (for example, forcing California fruit farmers to pay for advertising that extols California peaches). During the course of his argument, Campagne urged Justice Antonin Scalia not to buy green plums because “you don’t want to give your wife diarrhea.” He persisted in this scatological vein, obviously being tone-deaf to the reactions of the court. He lost the case, but there is no way of knowing whether the attempts at humor had an impact. It was just crude and unhelpful to his client. (The client sued him for malpractice after the oral argument. The malpractice case settled.)

THE JUDGE IS ALWAYS FUNNY

My father, who was a trial judge and then an appellate court judge for many years, loved to tell jokes in court. His tipstaff, the courtroom deputies and most of the gallery would laugh, and then he would come home and tell us what he said. My family thought the so-called jokes were not funny. We eventually realized that anytime a judge tells a joke, everyone has to laugh. I learned this lesson, literally at my father’s knee: Judges tell stories they think are funny. Laugh. And then get on with the case.

Whatever you do, don’t try to match the judge joke for joke. You are not at a comedy club. And you might find yourself torpedoing your client’s case. In Haluck v. Ricoh Electronics, a defense lawyer and the judge seemed to egg each other on to ever more frivolous comments. The 30-day trial ended with a defense verdict. The transcript included so many indecorous comments, I’ll just give you the appellate court’s summary, as it ordered a new trial:

“[The judge] allowed, indeed helped create, a circus atmosphere, giving defendants’ lawyer free rein to deride and make snide remarks at will and at the expense of plaintiffs and their lawyer. … It is obvious that much of the judge’s conduct was not malicious but rather a misguided attempt to be humorous; and defendants’ lawyer played into it, often acting as the straight man. But a courtroom is not the Improv and the presider’s role model is not Judge Judy.”

So my advice to you is: Don’t be funny. Your clients’ problems are serious, at least to them.

This article originally appeared in the November 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Don’t Be Funny: Litigation is no laughing matter to your clients.”

Janet S. Kole is a retired trial lawyer from Philadelphia and the author of numerous books, including Avoiding Bad Depositions: A Simple Guide to Complex Issues and the murder mystery Suggestion of Death.