Controversial Supreme Court decision lands on the big screen

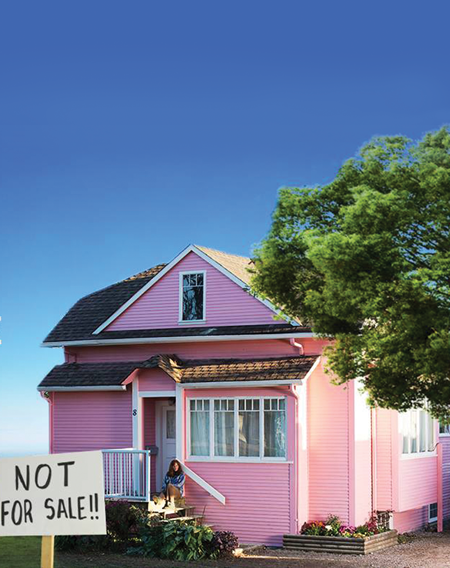

Photo courtesy of Korchula Productions

It’s rare to see a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision turned into a movie. But the case of Kelo v. New London uniquely galvanized a community, spurring one filmmaker to bring it to the big screen.

In the 2005 case, the Connecticut city of New London wanted to condemn the homes of Susette Kelo and her neighbors to make room for a redevelopment project. The waterfront land, in the blue-collar neighborhood of Fort Trumbull, would be used to build a hotel, shopping and other attractions. That is, Kelo would be displaced not for a road or a school but for the benefit of private businesses. She argued that this violated the Fifth Amendment, which requires just compensation when “private property [is] taken for public use.”

She lost 5-4. But the public reaction was almost uniformly sympathetic to Kelo’s plight, with disapproval cutting across political, geographic and racial lines. (One exception: Now-President Donald Trump, who at the time said, “I happen to agree with it 100 percent.”) One poll found that more than 80 percent of Americans disapproved of the decision and at least 45 states passed eminent domain reform laws in reaction.

“It just seemed like a terrible affront to justice,” says Ted Balaker, who runs the film company Korchula Productions in Culver City, California, with his wife, Courtney.

Balaker helped cover the case for ABC News, where he worked at the time. That’s how he got to know Kelo’s attorneys at the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public interest firm. Some time after he left to go into film, the firm called to tell him the film rights to Little Pink House, a book about the case by journalist Jeff Benedict, were available.

That launched the newly formed Korchula Productions into the yearslong process of making a movie. In addition to tasks like raising the money and securing the talent, they had the challenge of finding a house just like Kelo’s. This wasn’t easy for one of the reasons Kelo didn’t want to sell in the first place: It’s rare to find a home with waterfront views that she could afford with her income as a nurse and EMT.

“Susette couldn’t just move someplace else, because there’s no way she could have afforded to buy a similar house,” Balaker says.

They eventually found what they needed in British Columbia (though they had to paint it pink).

Another staging challenge was filming oral arguments before the Supreme Court—without access to the court. The filmmakers ultimately used an opera house, and set crews built interiors that Balaker says passed muster with several attorneys who had argued before the real court—including the attorneys who represented Kelo, who acted as legal consultants for the film. Screenwriter Courtney Balaker also used transcripts of the real trials as much as possible, Ted Balaker says—not only for authenticity but also to try to fairly represent the arguments.

“We wanted to give both sides the opportunity to lay out their best cases for why they thought they were right,” he says. “Even among our film crew when we were shooting, there was a lot of discussion.”

Little Pink House premiered in February at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival. Balaker hopes for a release in summer or fall, and Korchula Productions was still trying to find distribution at press time. For updates, check facebook.com/littlepinkhousemovie.

This article originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: "Just Compensation: A controversial Supreme Court decision lands on the big screen."