Moussaoui v. The United States

The terrorist needed to take a moment. So 121 people waited in silence in an overheated federal courtroom in Virginia, staring at the back of his balding head.

Zacarias Moussaoui wanted to review his confession (PDF). He didn’t want to sign anything that wasn’t absolutely, 100 percent true. The only person charged in an American courtroom in connection with the terrorist attacks of 9/11 appeared to be about to give up the fight, admitting to all the government’s charges without even striking a deal that would take off the table a possible sentence of death.

But Moussaoui, a month shy of his 37th birthday, had been down this road before, only to reverse course at the last minute. So there was more than a little uncertainty in Alexandria that day in April 2005. For almost two minutes, as he flipped through the pages, no one spoke. No one even coughed. When a reporter jotted a note, the pen scraping across his notebook could be heard from three rows back.

A Frenchman of Moroccan descent, Moussaoui was picked up on immigration charges three weeks before 9/11, after his instructor at a Minnesota flight school grew suspicious. Moussaoui had signed up to use a jumbo jet simulator, but could barely fly a Cessna.

He looked like a World Wrestling Federation villain at the time of his arrest, with a shaved head, close-cropped goatee and thick neck. Now a ring of thinning hair circled his pate and his full beard was untrimmed. His forehead was dark purple from hitting it on the floor during prayer and he’d grown bloated on jailhouse food. What hadn’t changed was his belligerence and his unpredictability.

COMING OUT SWINGING

Early in the case, he had fired his lawyers, invoking the almost-absolute right of federal defendants to represent themselves. Judge Leonie Brinkema had kept them on as standby counsel, filing motions on his behalf.

But inside the courtroom Moussaoui ran his defense, and he made the most of that stage.

The pretrial hearings were opportunities to butt heads with the judge. Standing perhaps 5 feet tall on a good day, the 61-year-old Brinkema wore her long, gray hair in a bun, bearing a striking resemblance to Mrs. Butterworth. Moussaoui sometimes referred to her as “grand nanny.” But he soon learned she subscribed to the “spare the rod, spoil the child” school of thought.

Trained in philosophy and library science before turning to the law, she had put away plenty of bad guys as an assistant U.S. attorney in Alexandria, eventually rising to head the office’s criminal division. She was a federal magistrate before President Bill Clinton elevated her to the U.S. District Court bench in 1993.

Lawyers call the Alexandria court the “rocket docket”—the front of the building is decorated with a depiction of a tortoise and a hare, along with the motto “Justice delayed is justice denied.” The Eastern District of Virginia—which stretches from the Washington, D.C., suburbs to the North Carolina line—routinely disposes of cases faster than any federal court in the nation. And in her courtroom, Brinkema was accustomed to absolute control.

You could set your watch by the time Brinkema took the bench, and if 15 minutes remained in the trial day, the lawyer called his next witness rather than knocking off early. When one of Moussaoui’s lawyers was 10 minutes late, she asked in jest if he had “brought [his] toothbrush”—suggesting his tardiness might earn him a night in jail.

But Moussaoui didn’t stick to the schedule because he didn’t know the script. In 2002, at what should have been a routine re-arraignment on a superseding indictment, Moussaoui tried to enter what he called a “pure plea”—neither guilty nor not guilty. Brinkema interpreted that as a plea of nolo contendere, which she wouldn’t accept. “I think I understand where you are confused,” she helpfully told Moussaoui.

“I’m not confused, thank you,” he replied in his heavily accented, often-fractured English.

JOUSTING WITH THE JUDGE

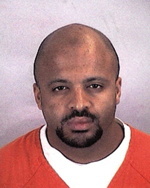

Moussaoui: In 2000

Moussaoui: In 2001, after arrest

It went downhill from there. Moussaoui said he wanted to testify in front of a grand jury—a rather novel strategy for most defendants—but he said prosecutors wouldn’t let him. “Now they are evading because they know that I have specific allegation and the knowledge of ongoing conspiracy, and they don’t want me to speak about,” he said.

“All right,” Brinkema replied.

“Yes, all right,” Moussaoui mocked. “Everything is all right. You’re just like making a …”

“Mr. Moussaoui,” Brinkema interrupted.

Moussaoui’s voice jumped an octave, imitating the judge: ” ‘You are sidetracking me, Mr. Moussaoui, Mr. Moussaoui.’ This is not justice, OK? Justice come in truth …”

“All right.”

“… and fairness. This is …”

“Mr. Moussaoui, I have told you many times before …”

“Yeah, you told me. I know what you told me.”

The hearing moved on to a humdrum discussion among the lawyers about prosecutors turning evidence over to the defense. But Moussaoui wasn’t done.

“I want to address my plea,” he interjected.

Brinkema wasn’t interested. “I’ve accepted a plea of not guilty, Mr. Moussaoui.”

“No, I didn’t make this plea.”

“I know, but I’ve entered one for you.”

An agitated Moussaoui charged ahead with his spiel. “I want to enter a plea. I want to enter a plea of guilty. I want to enter a plea today of guilty, because this will ensure to save my life, because this is conspiracy law. It’s much more complicated than what you want to make people to believe. Because even if I plead guilty, I will be able to prove that I have certain knowledge about Sept. 11, and I know exactly who done it. I know which group, who participated, when it was decided. I have many information.”

The heads of reporters snapped up from their notebooks. You could imagine them thinking, “Did he really just say that?”

“Wait a minute, Mr. Moussaoui,” Brinkema said, trying to regain control.

Moussaoui started talking faster, trying to get the words out before he was shut down. “But it will ensure me to save my life, because the jury will be, will be able to evaluate how much responsibility I have in this. But by carrying on with this farcical justice, I will be put aside soon, because already the standby counsel are speaking on my behalf in open court, where they are here only for protocol and procedure. You allow them to do this and to speak, and I will be soon, ah, removed from my defense, because you already put me on notice, OK, and what will happen to me, I will be certainly gagged during trial, ah, and you will carry on your so-called justice, and the jury will be inflamed, because Sept. 11, it’s a very serious affair, and they will, they pronounce my death.”

He kept going. “I, Moussaoui Zacarias, in the interests to preserve my life, enter with full conscience a plea of guilty, because I have knowledge and I participated in, in al-Qaida. I am member of al-Qaida.” It was as if all the air had been sucked out of the room.

Brinkema was momentarily outmatched, and she wasn’t happy about it. “Mr. Moussaoui, you have to stop, or I’ll have the marshals remove you.”

“I pledge bayat [an oath] to Osama bin Laden,” Moussaoui said.

“Marshals,” Brinkema commanded, and two burly security officers moved toward the defendant. Moussaoui raised his hands as if in surrender.

Just when it looked like Moussaoui had bested her, Brinkema won back control by letting go. “Mr. Moussaoui, all right, wait. Leave him one second,” she said to the marshals. Then to Moussaoui: “I’m going to advise you again that when you speak, the words you say can be used against you in the prosecution. If a defendant stands up in court and says, ‘I’m guilty of the offense,’ you may put yourself in a position where you cannot undo those words. When you—you can put your hands down, Mr. Moussaoui. When you plead—put them down.”

“Yeah, but I don’t want them to jump on me,” Moussaoui said, tossing his head at the marshals on either side of him.

“No one’s going to jump on you if you be quiet when I speak,” Brinkema said. She gave him a week to think about whether he really wanted to plead guilty.

“Bet on me. I will,” Moussaoui promised.

But, of course, he did not. The following week, during a long plea colloquy with the judge, a calmer Moussaoui admitted to some of the facts in the indictment but denied others. He eventually declared, “Dictated by my obligation toward my creator, Allah, to save my life and to defend my life, I have to withdraw my guilty plea.”

“This is not an unwise decision on your part,” Brinkema replied with enormous understatement, telling him “we had a very civilized hearing today.”

SETTING THE WORLD STRAIGHT

Three years later, when Moussaoui again sought to plead guilty, Brinkema held an extraordinary secret hearing—sans prosecutors—to make sure the defendant knew what he was doing. And two days after that Moussaoui returned to a rapt and overheated courtroom to review his confession in the statement of facts.

When he finally signed, he did so with the words “20th hijacker,” appearing at last to admit being part of the 9/11 conspiracy. But Moussaoui noticed what had eluded most of the media: The government never actually claimed he was involved in or even knew about the 9/11 plot. It simply claimed that he had been sent by bin Laden to fly a plane into the White House on an unspecified date, and that he had behaved in a fashion similar to those in the 9/11 plot.

Moussaoui wasn’t going to let the hearing end before setting the world straight. “My conspiracy has for aim to free Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman, the blind sheik [convicted in 1995 of a plot to blow up New York City bridges and tunnels], who is held in Florence, Colo., OK? And we wanted to use the 747 because it, it is a long-distance plane who could reach Afghanistan without any stopover to give a chance to special forces to storm the plane. So I am guilty of a broad conspiracy to use weapon of mass destruction to hit the White House if the American government refuse to negotiate, OK?”

“Everybody know that I’m not 9/11 material,” he added. As for that 20th hijacker reference, he said months later that it was just “a bit of fun.”

I watched the twists and turns of the Moussaoui case from a reserved seat on the back row of the courtroom’s spectator gallery. Trained as a lawyer, I had been a legal journalist for more than a dozen years. The court hired me to advise it on issues related to the media, and to serve as an intermediary between the judge and the hundreds of reporters who were covering the Moussaoui trial and other high-profile cases.

My business card said I was the public information officer. But Moussaoui was his own public information officer. “We’ve got to be here,” a CNN producer told me, “because we never know what the hell he’s going to say.”

What was billed as United States v. Moussaoui became Moussaoui v. the United States.

Moussaoui used his case as a way to wage jihad by other means. He fought with the judge. He fought with his lawyers. Eventually, he fought with the prosecutors in a riveting cross-examination. But all of those battles were in service of his larger cause—as a warrior for radical Islam against the West.

Moussaoui’s theatrics gave rise to a debate over whether it was better to try al-Qaida members in civilian courts or military tribunals. I think that obscures the more important issue.

Whether the trial takes place in a courthouse or on a military base, the real venue is the court of world public opinion. Location matters much less than whether defendants are given—as Moussaoui surely was—a full measure of due process, which is the hallmark of true justice.

Public trials in which defendants have substantial rights, and in which prosecutors must clear high hurdles to win convictions, contribute to America’s greatness. We have maintained those procedures and survived for centuries, even in the face of enemies far fiercer than al-Qaida.

But for America to deliver on the lofty promises of the rule of law, ordinary lawyers have to do extraordinary things in the toughest of cases. It takes a judge like Brinkema, who is strong enough to keep the proceedings on track but not so controlling as to entirely shut the defendant out of the process. It takes a prosecution team that will let the facts speak for themselves, rather than screaming for retribution. And it takes defense lawyers who are willing to do battle for a client who tells them to go to hell.

It was after midnight on April 16, 2002, when defense counsel Frank Dunham, 59, started writing a letter (PDF) to Moussaoui. He’d been working on the case at his kitchen table since his wife cleared away the dishes hours earlier. And he was fed up.

“You … accuse me of dropping information on you in an innocuous manner when I think you will disagree with it. Nothing could be further from the truth. The truth is that you disagree with almost everything,” he wrote.

A former assistant U.S. attorney in Alexandria—where he was a colleague of Brinkema’s when she was a prosecutor—Dunham got the case of a lifetime when he was least prepared. In December 2001, when Moussaoui was indicted, Dunham had just been tapped to set up the Office of the Federal Public Defender for the Eastern District of Virginia. He didn’t even have office space or staff in Alexandria when the case began, and he was forced to work out of temporary quarters in the courthouse.

Every Saturday morning, he routinely stopped by the Alexandria Detention Center five blocks from the courthouse, where federal marshals rented space to house Moussaoui. Sometimes lawyer and client talked about the case, but often they talked about their backgrounds and current events.

Rotund and generally rumpled, Dunham brought an appealing everyman quality to a case burdened by the weight of history. When a reporter who was mentioned in one of Moussaoui’s handwritten pleadings called Dunham to ask if he should be concerned for his safety, Dunham replied, “Get in line. You’re probably 50th on the list of people he wants to get. I’m in front of you, and if he gets all the way to you we’re in bigger trouble than we think.”

Dunham brought passion to his work. When he read in a newspaper that Yaser Hamdi, an American citizen who was picked up on the battlefield in Afghanistan, was being held as an enemy combatant in a naval brig in Virginia, he talked his way into serving as Hamdi’s lawyer.

Dunham sought a hearing to determine whether Hamdi was indeed an enemy combatant. He personally argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court, where he bluntly told the justices they should “step up to the plate” and declare Hamdi’s detention unlawful.

He won, and the government returned Hamdi to freedom in Saudi Arabia rather than give him a hearing.

BRINGING IN THE HEAVYWEIGHTS

In the Moussaoui case, Dunham brought on Gerald Zerkin, 53, from the public defender’s Richmond office. Zerkin had battled the prosecution’s death penalty specialist, Assistant U.S. Attorney David Novak, in three previous capital cases, winning life sentences in each. Edward MacMahon, 42, a dapper lawyer from the hunt country of Middleburg, Va., was appointed by the court to assist. Ironically, when President George W. Bush took office, MacMahon had been on the short list as a potential U.S. attorney in the Eastern District. Also appointed by the court was Alexandria solo practitioner Alan Yamamoto, 57, whose parents had been sent to a Japanese internment camp during World War II. The way Muslim-Americans were treated after 9/11 made him think “history has not taught anybody anything,” he told a reporter.

Writing from his kitchen table, Dunham addressed disagreements small and large. Moussaoui wanted the first row of the spectator gallery to be empty to build sympathy for him. But “the empty row—instead of showing the absence of family—could suggest that the marshals are so concerned about your dangerousness that they have kept the row closest to you empty,” Dunham wrote. (During the trial, the row was empty for just that reason.)

Moussaoui hated that Zerkin, who is Jewish, was handling the death penalty phase of the case, and he claimed Dunham was trying to hide that fact from him. “You say it is ‘regretful and disturbing that you have been keeping silent about Zerkin preparation,’ ” Dunham recounted. “I say it is regretful and disturbing that something I thought has been clear for many months has apparently slipped your mind so completely.”

“I never assume that because you do not express disagreement on one day that this means you will agree, because your pattern is to flip-flop on everything,” Dunham wrote.

Five days later, Moussaoui was in court asking to go pro se. “They appointed, imposed the dream team. Greed, fame and vanity is their motivation. Their game is deception. Their slogan is no scruple,” he said.

After a competency review by a psychiatrist, Brinkema granted his request. What followed, until Brinkema revoked his pro se status 17 months later, was a daily stream of motions from Moussaoui. Of the hundreds he filed, most were frivolous—and almost all contained what Brinkema called “contemptuous language that would never be tolerated from an attorney.”

He called Brinkema the “death judge” and a “bitch” who would “burn in hell.” Dunham was labeled a “fat megalo[maniac],” Yamamoto was a “fake kamikaze” and a “geisha,” and Zerkin was a “Jew bastard.”

Moussaoui later described those filings as “part of my propaganda, OK, I make no apology, OK. I was cursing you because you were trying to kill me.”

UNCOVERING THE KEY

Despite the name-calling, the defense counsel soldiered on—though Dunham had to drop out before the trial because of brain cancer. It took his life last year. So that Moussaoui couldn’t gloat over the misfortune of his lead lawyer, Dunham’s illness was never mentioned in court.

Dunham & Co. fought hard for access to what turned out to be the key piece of evidence in the case—and their battle proved that Moussaoui had the same rights as any other defendant.

The defense convinced (PDF) the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Richmond—widely regarded as the most conservative appellate bench in the nation—to compel the government to disclose summaries of statements by al-Qaida members who had been detained by U.S. forces overseas after 9/11 (though counsel lost their bid to directly question those individuals). That included statements by Khalid Sheik Mohammed, the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks.

Mohammed told interrogators that Moussaoui was meant for a second wave of airplane attacks that were to have taken place at a later date. Moussaoui knew nothing of the 9/11 planning or who was involved in that operation, Mohammed said.

Mohammed’s account (PDF) differed in details from Moussaoui’s claims at his plea hearing, but it provided support on the most crucial point—Moussaoui could not have helped investigators uncover the 9/11 plot because he didn’t know about it. So the lies he told the FBI in Minnesota—that he was learning to fly to become a private pilot—didn’t cause anyone’s death on 9/11, the defense theory went.

But Moussaoui couldn’t leave well enough alone. Over the objections of his lawyers—they failed repeatedly to get him declared incompetent—he insisted on testifying at his trial. The purpose of the two-month trial was to determine whether he caused someone’s death on 9/11 and, if so, whether he should be sentenced to life in prison or death.

When he took the stand on March 27, 2006, he told yet another story about why he was taking flying lessons. Gone was any mention of the plot to spring Abdel Rahman from prison. In its place was his claim that he was to crash a fifth plane into the White House, and that shoe bomber Richard Reid was to be among his crew.

He gave prosecutors a gift by claiming—as he had not at his plea hearing—that the operation was to have taken place on 9/11, and that he knew two planes were to hit the World Trade Center in the same operation.

“You lied to [Minnesota FBI] Agent Samit, is that correct?” Zerkin asked him.

“That’s correct,” Moussaoui replied.

“And why did you lie to him?” Zerkin asked.

“Because I wanted my mission to go ahead,” Moussaoui said.

That was the government’s case, in a nutshell. The jury found Moussaoui eligible for the death penalty—that, were it not for his lies, the government would have been able to stop the hijackers from taking over at least one of the four planes on 9/11. Now that he was eligible, the jurors had to determine whether he should be put to death. But not before hearing three more weeks of testimony, including dozens of heart-wrenching stories of loss from family members of 9/11 victims.

GETTING TO THE POINT

Against that backdrop, which a juror later described as “like attending one funeral after another for days on end,” Moussaoui again took the stand. The cross-examination by lead prosecutor Rob Spencer embodied the clash of civilizations that Moussaoui had worked years to achieve.

Unlike the vengeance-is-mine attitude of so many prosecutors, Spencer, 44, exuded rectitude and decency. He established a rhythm with Moussaoui, asking short questions and getting to-the-point answers. Eschewing histrionics, he kept his voice modulated—denying Moussaoui the chance to play David to Spencer’s Goliath. Moussaoui followed his cue with a matter-of-fact tone that made his answers all the more chilling.

“You told the jury that you have no regret for your part in any of this?” Spencer asked.

“I just wish it will happen on the 12th, the 13th, the 14th, the 15th, the 16th, the 17th, and I can go on and on,” Moussaoui said.

“No remorse?”

“There is no remorse for justice.”

“You also enjoyed … the testimony about the attack on the Pentagon?” Spencer asked.

“Definitely.”

“You smiled at times during that testimony, didn’t you?”

“That’s for sure,” Moussaoui said, a small smile playing at his lips. “I would have even laughed if I didn’t know that I would be kicked out of the court.”

“Right. You enjoyed seeing the Pentagon on fire.”

“My pleasure,” Moussaoui said. Spencer was leading Moussaoui exactly where Spencer—and Moussaoui himself—wanted to go.

“And you remember hearing Lt. Col. John Thurman describe he had to crawl out with his face against the floor to save his life?”

“He was pathetic.”

“You enjoyed that, didn’t you?”

“I was regretful he didn’t die.”

“Well, here is somebody who did die,” Spencer said, as a paralegal flashed a victim’s picture on the courtroom’s screens. “Do you remember that gentleman?”

“I remember his wife, the blond-haired girl,” Moussaoui said.

“That’s Vince Tolbert, who worked for the United States Navy, right? He was killed on 9/11 in the Pentagon.”

“Yes, the one that said to her children that some bad people have killed her husband. And she forgot to tell to her children that her husband was working classified, something about targeting.”

“And it made you particularly happy that he was killed that day, correct?”

“Make my day,” Moussaoui replied.

“Do you remember the testimony of Lt. McKeown?”

“The woman like was talking about: Where are my boy, where are my boy?”

“Right,” Spencer said, “sobbing in that very chair because the people under her command were killed. Do you remember that?”

“I think it was disgusting for a military person to pretend that they should not be killed as an act of war. She is military. She should expect that people who are at war with her will try to kill her. I will never, I will never cry because an American bombed my camp.”

“And you were happy that her two men were killed that day?”

“Make my day.”

“All right,” Spencer said. “You were happy that every single person who came in here sad, telling about the effect that you and your brothers [had], you were happy about all that, weren’t you? No regret, no remorse—right, Mr. Moussaoui?”

“No regret, no remorse.”

“Like it to all happen again, right?”

“Every day, until we get here to you.”

Even though Moussaoui “mocks and taunts family members whose loved ones died,” his “role in 9/11 was actually minor,” an anonymous juror told the Washington Post after the verdict came down. After 41 hours of deliberation, that juror was the only one (PDF) to vote against the death penalty on the lead count of conspiracy to commit acts of terrorism transcending national boundaries, thus saving Moussaoui’s life.

At Moussaoui’s sentencing hearing, the last word belonged to Brinkema. “Mr. Moussaoui, you came here to be a martyr and to die in a great big bang of glory, but to paraphrase the poet T.S. Eliot, instead you will die with a whimper. The rest of your life you will spend in prison. You will never again get a chance to speak, and that is an appropriate and fair ending.”

Sidebar

PDF transcripts of the hearing in which Zacarias Moussaoui attempted to plead guilty, the hearing in which he did, and the trial session in which he testified.

Video of Moussaoui being transported to prison after conviction