Native Hawaiians wage an ongoing battle to organize into a sovereign nation

Shutterstock

Native Hawaiians have been considered Americans for more than 100 years. But they haven’t forgotten the original sin that created their state.

That sin—the forcible ouster of the Hawaiian monarchy—has some Native Hawaiians waging a legal battle to this day to regain some measure of independence.

Under the monarchy, American and European businesspeople had prospered. But they wanted control in this land of paradise. So in 1887, they assembled a militia and forced King David Kalākaua at gunpoint to sign the Kingdom of Hawaii Constitution, nicknamed the “Bayonet Constitution,” which reduced his power and increased the power of wealthy, white landowners.

See images of Hawaii’s path from monarchy

When the king’s sister, Queen Lili‘uokalani, inherited the throne a few years later, she was determined to reverse this imbalance of power by writing a new constitution. But backers of the Bayonet Constitution got word of the plan. On Jan. 16, 1893, they gathered their militia across from her palace. The U.S. minister to Hawaii, John L. Stevens, ordered about 160 armed American troops to come ashore—ostensibly to protect American property, but most of the troops set up camp near the palace.

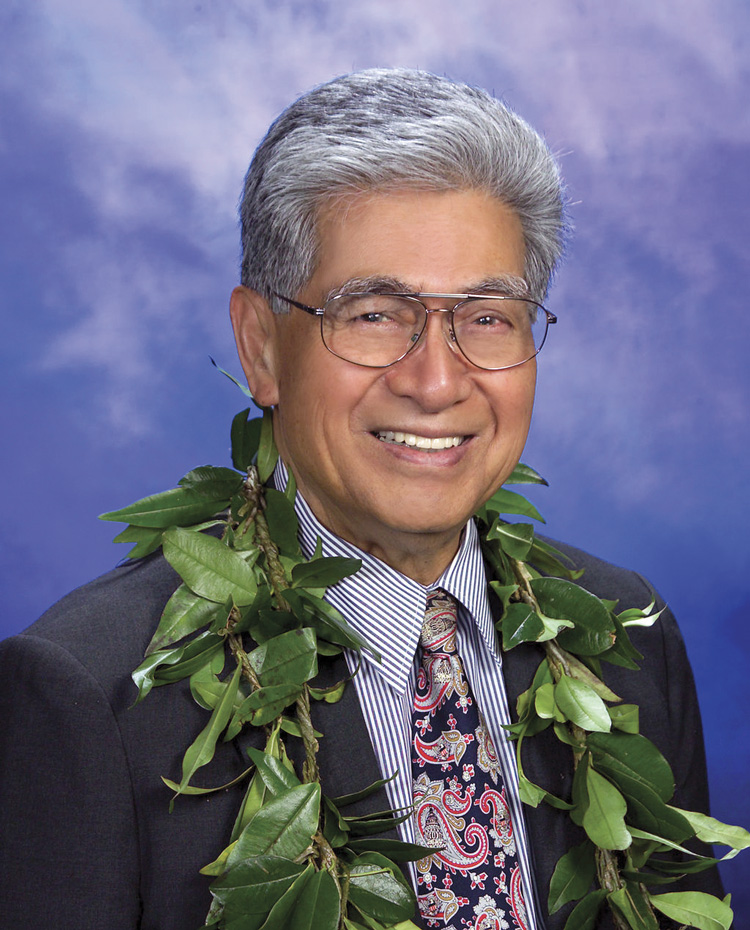

Former Hawaii Sen. Daniel Akaka, a Democrat, introduced yearly bills to achieve sovereignty. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

At dusk the next day, fearing a war, the queen gave up her throne. “Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces—and perhaps the loss of life—I do, under this protest and impelled by said forces, yield my authority,” Lili‘uokalani wrote.

Despite good relations between the United States and the kingdom, American leadership never intervened actively to reverse the overthrow. The United States annexed Hawaii in 1898—without the consent of its people or its former queen—and declared it a state in 1959.

But Native Hawaiians haven’t forgotten that they were once independent. They’ve been trying to regain that independence for decades—especially since the 1970s, when there was a renaissance of interest in Hawaiian culture. The state’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs was established in 1978 to support sovereignty; former Hawaii Sen. Daniel Akaka, a Democrat, introduced yearly bills to achieve it; and islanders have tried several times to organize a vote on whether to form a Native Hawaiian government.

But those votes have been challenged repeatedly—and in 2000, one of those challenges resulted in a U.S. Supreme Court precedent that has stymied self-governance efforts since then. Rice v. Cayetano held that under the 15th Amendment, which expressly says states may not deny any citizen the right to vote based on race or color, a Hawaii state agency may not hold elections only for Native Hawaiians.

Photo of Queen Lili’uokalani courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

That means current efforts are in danger. A 2016 constitutional convention, called an ‘aha in the Hawaiian language, produced a proposed constitution for a Native Hawaiian government, whose form and relationship to the United States is not yet settled. But the ‘aha also got organizers sued for violating Rice. That forced them to rely on private funding to ratify the constitution. As of December 2016 (the most recent data provided), organizers had only a little more than an eighth of the money they need. Opponents of the effort are watching closely for anything they think is illegal.

“We are actively involved in making sure that we’re ready to go if this rears its head again,” says Robert Popper, director of Judicial Watch’s Election Integrity Project. “There is going to be a serious ... problem no matter how they structure this, and we are dedicated to making that argument.”

This article appeared in the November 2017 issue of the