A Father's Mission: Victim's dad demands to know why 4 child murders remain unsolved after 40 years

Barry King. Photographs by Wayne Slezak.

Barry King, an attorney and father of four, went on television on the evening of March 18, 1977, with a message to his 11-year-old son, Timothy, who had been missing for two days. King was hopeful that his son was OK, but he feared the worst: Three children had already been snatched from the streets of his suburban Detroit community and murdered during the last 13 months.

“We’re with you, buddy,” King said as he stood outside the Birmingham, Michigan, police station. “We love you. God bless you. Stay tough.”

King also had a message for the person who may have abducted Tim. “I don’t know if you have a child or want to have children, but please treat Tim as you would your own kid.”

For the past 48 hours, police had been searching block by block for the sixth-grader in and around Birmingham. Tim was last seen at a pharmacy three blocks from home, where he’d gone on his skateboard to buy candy.

Six days after Tim disappeared, the King family was home watching Johnny Carson when a news bulletin appeared: A boy’s body was found in the nearby town of Livonia. A few hours later, the police chief and a priest came to the house bearing the news: It was Tim.

The Oakland County Child Killings, as they became known, left deep scars on the King family, on the families of the other victims and among those who lived through it during the late 1970s. The events forever changed a community where kids once played outdoors freely and without worry. Instead, parents instructed their children to come right home after school, play in their own yards and never talk to strangers.

The murders sparked one of the largest investigations in the U.S. and included a task force of 200 local, county and state police, as well as the FBI. Investigators sifted through some 20,000 leads and interviewed thousands of people. They consulted with psychologists, criminologists—even a hypnotist. King thought the police were doing an extraordinary job, and he was confident that the killer would be brought to justice.

Forty years later, the murders remain unsolved, and King’s view of the investigation eventually changed. He believes that police made many mistakes and squandered opportunities to solve the case. Now 85 years old, King has been on a campaign to find the truth and hold authorities accountable.

In his effort to shed light on the investigation, King has filed freedom of information lawsuits seeking case files. He’s also hounded authorities to explain why some suspects were cleared, particularly a man he believes was the most promising: the now-dead son of a former General Motors executive who had been questioned and released just before Tim’s murder.

“The legal system,” King says, “has failed us.”

TERROR IN OAKLAND COUNTY

Oakland County is about 28 miles northwest of Detroit. It’s a mostly upper-middle class collection of suburbs, including Birmingham, where the King family lived along with other white-collar professionals. Barry King practiced general law at a small firm, doing mostly civil litigation. He lived on Yorkshire Road with his wife, Marion, and children Tim, Mark, Chris and Cathy.

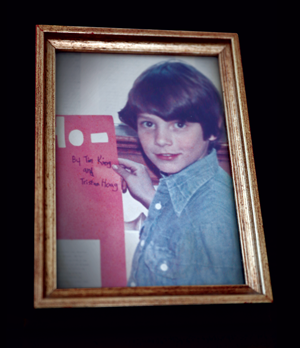

Timothy King was last seen at a store three blocks from his house. He’d gone out to buy candy on his skateboard, which his killer left near his corpse six days later.

Tim was an active kid who loved to play baseball and hockey and zoom around on his skateboard. “His world was the neighborhood, his school, paper route and the parks where he played sports,” King recalls. “He was everybody’s friend.”

The days of carefree play ended in Oakland County on Feb. 15, 1976, when Mark Stebbins, 12, was abducted from the town of Ferndale. His body was found four days later in nearby Southfield. Ten months later, on Dec. 22, Jill Robinson, also 12, was taken from Royal Oak. Her body was found in Troy, about 5 miles from her home, on Dec. 26. On Jan. 2, 1977, Kristine Mihelich, the youngest of the victims at age 10, was taken in Berkley and found dead 19 days later in Franklin.

Two months later, passers-by found Tim’s body, still warm, in a roadside ditch in the town of Livonia, just over the border in Wayne County. He had been sexually abused and suffocated, his wrists and ankles bruised by rope marks. The killer had cleaned Tim’s body and washed his clothes before placing him on the side of the road with his skateboard. The other victims also had been found washed and in clean clothes.

When the King family arrived at the funeral service, they saw undercover police taking surveillance photos of people in the parking lot and walking into the church. Tim was dressed in a blue warmup suit, his coffin covered in a floral rendition of a baseball and bat.

The police task force continued its investigation, headquartered in an abandoned school building. Investigators worked up a psychological profile of the suspect—a white man with above-average intelligence, obsessed with cleanliness, possessing an air of authority and appearing trustworthy to children, and living in or around the community. In one of the most publicized leads of the case, investigators said a witness reported seeing a boy with a skateboard in the pharmacy parking lot talking to a man possibly driving a blue AMC Gremlin with a white stripe. Police drew a composite sketch of a man with shaggy hair and bushy sideburns.

Barry King went back to work a few days after his son’s funeral, doing his best to get on with life. He trusted that police would bring the killer to justice. He never talked about it much after that. “I was always more concerned about tomorrow than yesterday,” King says.

His wife, Marion, however, found it hard to cope, and the children would suffer their own psychological wounds in the months and years to come. No one really talked about it at home, as if the subject were taboo, as if it would hurt too much. “His mother was never the same,” King says of Marion.

In December 1978, after spending its $2 million budget, the police task force disbanded, and the Michigan State Police took over the case. The killings had stopped with Tim, and some theorized that the murderer might have moved away, got arrested for other crimes or possibly died.

During the next 30 years, Cathy became a lawyer, got married, had children and moved to Idaho. Mark became a businessman, eventually moving to Texas, and Chris an editor and tech writer in Michigan. Barry King continued to practice law.

“We just couldn’t talk. My mom was so broken by this,” recalls Cathy, now Catherine King Broad. “I felt I could never bring it up.”

Marion died in 2004—never seeing her son’s killer brought to justice.

A SECRET REVEALED

Throughout the years, police zeroed in on several suspects, some of whom were convicted child molesters and purveyors of child pornography. They even exhumed the body of one suspect, but that lead hit a dead end—like so many others.

But in 2005, Michigan State Police Detective Sgt. Garry Gray announced the department was reviving the task force on a smaller scale, explaining that advanced forensic techniques and the availability of new computer databases would allow them to re-analyze old evidence. Once again, the King family went about their lives, assuming the police were doing their best.

That assumption changed after Chris King and his sister, Broad, got a call in 2006 from a childhood friend, Patrick Coffey, who had explosive news. Coffey had become a polygraph examiner and was living near San Francisco. He said he had just met another polygraph examiner at a conference in Las Vegas who confided that he conducted a polygraph on a man who admitted killing one of the Oakland County children.

The examiner was Lawrence Wasser, who heard Coffey speak at the conference and invited him to speak in Michigan. Coffey mentioned he once lived in Michigan and explained he became a polygrapher, in part, because of Tim’s murder. He asked Wasser whether he had heard about the Oakland County Child Killings.

Coffey says Wasser suddenly appeared shaken and then revealed that he tested a man 30 years ago who was suspected in the killings. Though the suspect confessed to killing one of the children, he was cleared by police. Wasser said the suspect had since died, as did his attorney. He declined to name either one, which Wasser considered a breach of professional ethics. Coffey hoped that Wasser might be willing to share the information with police. He later reached out to Wasser but never heard back.

Barry King spent $12K on a suit to find out why police stopped following a key suspect.

Meanwhile, in December of 2006, members of the police task force announced the arrests of two men on child molestation charges who were being questioned in the murders: Theodore Lamborgine, 65, and Richard Lawson, 60. The pair were accused of sexually molesting children during the 1970s and 1980s. But neither was ever charged in the Oakland County killings.

One of the lead detectives investigating Lamborgine and Lawson was Cory Williams from the police department in Livonia, the town where Tim’s body was found. Williams had met Barry and Chris King along with other members of the Michigan State Police task force to discuss the arrests, and the Kings took a liking to him.

Broad felt it was time to do something with the information she got from Coffey about Wasser’s polygraph claim. But she feared the task force would ignore her tip. She had become cynical after reading stories and blogs about people who claimed that many of their tips to police were dismissed. Broad also reviewed old news articles and concluded that the investigation had been mired in problems.

“Up to that point, I drank the Kool-Aid that the police did their best,” she says.

Broad decided to call Detective Williams, who had left the state task force after some disagreements, and tell him about Wasser. Broad asked Williams not to share her tip with state police. So instead, Williams contacted the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office, which had jurisdiction where Tim’s body was found.

The prosecutor’s office issued an investigative subpoena compelling Wasser to identify the person he polygraphed. Wasser subsequently helped police by hinting which file folder among several splayed on a desk contained the right name. By doing this, Wasser could preserve his reputation and ethical standing by not technically giving up the name.

His name was Christopher Busch.

The name wasn’t familiar to Broad, but genealogical research led to a death certificate for a Christopher Busch who lived in nearby Bloomfield Township. He had committed suicide in 1978 at age 27.

The Kings learned that Busch was a convicted pedophile, though he never served time in prison. His father was the late Harold Lee Busch, an executive financial director for General Motors. And it turned out that police had questioned Busch three weeks before Tim was abducted. He’d been polygraphed and cleared.

Wasser later denied ever talking to Coffey about polygraphing a suspect in the case, calling his story “bogus” and suggesting that Coffey sought recognition and wanted to write a book. Coffey responded by filing a libel suit, which he later dropped after Wasser agreed to withdraw his allegations. Wasser did not respond to ABA Journal requests by phone and email to discuss the case.

The Kings believed Busch should have been a strong suspect, but the police would not reveal much more about what evidence they collected or the progress of the investigation into Busch.

The Kings did learn that Busch had been arrested in Flint, along with a man named Gregory Greene, in 1977 on charges of molesting and photographing boys. The men were also questioned about the death of Mark Stebbins and passed polygraph exams, according to police accounts. The Traverse City Record-Eagle published stories linking Busch to a child pornography operation on North Fox Island, where a group of men were accused of using a religious mission as a front for their activities.

The Kings filed a freedom of information request with the Bloomfield Township Police Department for the Busch autopsy report. The department said the file had been destroyed. Yet a local reporter later got the file, which deepened the King family’s distrust of the police. The report listed the cause of death as a self-inflicted gunshot wound from a rifle. While investigating, police found a drawing pinned to Busch’s bedroom wall of a screaming boy wearing a hooded jacket, and it resembled Mark. They also found rope on a closet floor stained dark red.

Broad and Chris King were upset to learn the police had never told them about Busch. “At this point they were just keeping us in the dark,” Chris says. Broad finally decided to tell her dad about the call from Coffey and the Busch lead. The family requested to meet with the Michigan State Police to learn more about the investigation. Meetings were set up and then canceled. Finally, in October 2009, King—along with son Chris and Erica McAvoy, the sister of Kristine Mihelich—met with the task force, but King says no one answered their questions and they left frustrated.

SUING FOR INFORMATION

King learned from the former Birmingham police chief that in 2010 the task force had stopped following the Busch lead. King tried to get someone at the Michigan State Police or the Oakland County Prosecutor’s Office to explain why, but no one would. He enlisted the help of family friend Lisa Milton to file a lawsuit in 2010 against the state police for investigative files.

“When he started asking questions was when they started being resistant,” Milton says.

King won the suit, and police turned over 3,411 pages of evidence, which King says cost nearly $12,000 in fees and copying costs. He pored through the files, which confirmed much of what he already knew about Busch and, in his mind, underscored that he should remain a prime suspect. “There was nothing exonerating Busch,” King says. “That’s what I was looking for—something to indicate that he wasn’t involved. I haven’t seen anything that excludes him.”

The files also contained information that matching white hairs, likely from a dog, were found on the clothing of all four victims. In addition, DNA evidence was retrieved from a human hair found on Kristine’s body. The sample was poor and would only allow police to make what’s known as a mitochondrial DNA match, meaning that the DNA profile could be matched not just to one person but also to that person’s mother, all her children, her siblings, her mother or other maternal relatives. Police said the profile matched a suspect named James Gunnels, who had an arrest record for property crimes but was never charged in the murders. A local television station, WDIV, reported that Gunnels, who was 16 at the time of the murders, had been molested by Busch and may have been involved in a plot to lure children to him.

King, disturbed that investigators had never shared this information, demanded a meeting with Oakland County Prosecutor Jessica Cooper, who took office in 2009. He also filed more FOIA requests to no avail. He argued that the Michigan Constitution entitled him to the files as a victim, and that he had the right to confer with the prosecutor. “All I’ve asked from anyone is the reason they stopped treating Busch as a suspect,” King says. “If they have a good reason for doing these things, tell me.”

Cooper says she’s been put in the difficult position of having to deny the many requests of a grieving father. In an interview with the Journal, Cooper says that she did, in fact, meet with King, and that the chief assistant prosecutor, Paul Walton, also met with King at his home to discuss the case. “It’s very frustrating for him,” Cooper says. “I feel great compassion for someone who has lost a child. But I don’t have unlimited time and resources. Nobody is going to rest, and I don’t know if there will ever be an answer.”

The relentless push by the Kings, along with stories in newspapers and on television, prompted Cooper to post a report on the Oakland County prosecutor’s webpage to separate fact from myth about the case. Cooper’s office points out that in the 40 years since the murders, dozens of police chiefs have led thousands of officers on the case and that four different prosecutors have served in office. They waded through conspiracy theories, false leads and dead ends. Information was not digitized as it is today, so it was difficult to exchange or cross-reference.

“The right hand didn’t know what the left hand was doing,” Cooper says. “DNA evidence was unheard of then.”

Cooper says investigators have since scanned and digitized thousands of pages of documents, and have combed through them all again. “We are still pursuing new leads and still doing what we can.” But her office still cannot share information with the Kings or anyone else because, she explains, it’s an ongoing investigation and contains attorney work product. “He wants a declaration that I can’t give him,” Cooper says.

The Michigan State Police won’t say much either. Lt. Michael Shaw says, simply, that the case remains under investigation.

“It’s the same thing year after year,” says McAvoy, Kristine’s sister. “The state police and task force are so uncertain.”

In the fall of 2012, former suspect Gunnels contacted Barry King and requested a meeting in Kalamazoo to clear the air about his suspected involvement in the murders. King and his son Chris visited Gunnels in October at the home of his Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor. Gunnels told the Kings he had been molested by Busch, but knew nothing of the killings and could not link him to them.

There were other suspects in later years, but none panned out. In his continuing effort to draw attention to the case, King produced a DVD in 2013 in which he and his family recount the story and discuss the investigation. The proceeds benefit a fund set up in Tim’s name to help abused children and support youth activities.

PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT

King’s efforts on behalf of his son, as well as his criticisms of the police and prosecutor, are much like those of another grieving—and very famous—father: John Walsh, the victims’ advocate and television personality whose 6-year-old son, Adam, was murdered in 1981.

Adam went missing from a mall in Hollywood, Florida. His severed head was found two weeks later, but the rest of his body was never found. The investigation yielded no arrests for more than 25 years as Walsh became an advocate for missing and exploited children and host of America’s Most Wanted.

In 2008, police announced a break: They had concluded that a drifter and convicted serial killer named Ottis Toole murdered Adam. Toole, an associate of the serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, had confessed to killing Adam, but he recanted before dying in prison in 1996. Detectives believed Toole was the killer based on an accumulation of evidence over the years.

Walsh, writing in his 1997 book Tears of Rage, asserted that the case was completely botched. While Walsh had been opposed to police releasing investigative files to the public, he said the files revealed that the investigation had been “a disaster” from the beginning. Among his criticisms was poor coordination among police agencies and inexperience in handling homicide cases. “Everything seemed so chaotic and disorganized,” Walsh wrote.

Also in Florida, the parents of Tiffany Sessions, 20, who disappeared from the campus of the University of Florida at Gainesville in 1989, worked for decades to keep the investigation alive. Patrick Sessions, a Miami real estate developer, used his own money and connections to keep the case in the media. His ex-wife, Hilary, who also was deeply involved, helped create a missing person’s act in Tiffany’s name and became a nationally recognized victims’ advocate.

In February 2014, there was a break in the Tiffany Sessions case. The Alachua County sheriff announced that investigators identified a convicted rapist and murderer as the all but certain killer of Tiffany, whose remains were never found. He was Paul Eugene Rowles, a serial killer who had left diary entries that contained notes about his killings and what seemed like a reference to the abduction and murder of Tiffany. Rowles, however, had died a year earlier.

Kevin Allen, the cold case detective from the sheriff’s office who led the investigation, says the family’s unrelenting commitment to solving the case made a big difference. “In most cold case investigations, if the family doesn’t push, there is very little done at the investigative level,” he says.

Hilary and Patrick Sessions knew the value of using the media to keep the story, and the investigation, from slipping into obscurity. “Anything you can do to create a hook to get the media to come out and law enforcement to come out is valuable,” Hilary Sessions says. And though her daughter’s remains have yet to be found, she has found some comfort and relief in knowing that police have identified the killer, even though he’s dead.

A FATHER’S BLOG

Barry King still lives in the same home on Yorkshire Road with his second wife, Janice, who had been a friend of Marion’s. Photos of Tim are displayed in the living room, along with a painting of the boy in a hockey uniform.

King writes a blog to bring yet more attention to the case. His posts include photos and documents he obtained through his lawsuit, along with correspondence with police and the prosecutor’s office. “I’ve enjoyed it because in a way, it’s given me an opportunity to vent,” King says.

“Here’s a guy who’s 85 and he’s going to keep plowing ahead in hopes that this might help someone remember something,” King’s son Chris says. “He’s a man on a mission and he’s going to keep at it.”

Despite the family’s campaign to keep the case in the public eye, it’s been a difficult journey. “There’s no upside. It has re-traumatized us,” Chris King says. “It’s such an open wound within the community. If there can just be some kind of closure in the case, that would be helpful.”

Broad says police owe the families an explanation. “They should reveal what went wrong with the investigation and say this is why we couldn’t put together the case,” she says. “At some point they have to stop hiding behind the active investigation. Tell the public what went wrong. Innocence is damaged in Oakland County forever. I think they owe it to those four kids to come clean and explain why they have no answers.”

Detective Williams believes Barry King’s work has been extraordinary. “I’m proud of Barry, as a father, how far he’s carried the torch for his son and never gave up,” Williams says.

Perhaps the most poignant reminder of Tim is a gift he gave his dad, a piece of wood on which Tim painted “Happy birthday, dear Dad. Best wishes, Tim.” Tim told his dad that the piece of wood was the best he could do because he had no money.

“I told my family,” King explains, “that when I go to the crematorium, I want this to go in with me because I want to take Tim with me.”

Correction

Due to an editing error, print and initial online versions of the caption for the photo of Timothy King in “A Father's Mission,” February, should have stated that his killer left the boy’s skateboard near his corpse six days later.The Journal regrets the error.

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: "A Father’s Mission: 40 years after 4 children were abducted and murdered in suburban Detroit, a victim’s father is demanding authorities explain why the cases remain unsolved."