Uniform Bar Exam Is Picking Up Steam

The possibility of creating a single bar exam that could be taken by recent law graduates in all the states has intrigued members of the bar admissions community for decades. But now it appears that the framework for a viable uniform bar exam is in place. Moreover, a combination of factors—from a tough legal job market to the increasing globalization of the profession—has helped the idea gain support.

“The time finally seems right because we’re talking about moving lawyers across lines in ways we didn’t 20 years ago,” says Erica Moeser, who is president of the National Conference of Bar Examiners in Madison, Wis. “These are tough economic times for new graduates to be emerging from law school, and making the wrong guess on where that first job is can have tremendous consequences.”

That’s a dilemma someone like Brett E. Gallagher can appreciate. A resident of Chicago, she graduated from Northeastern University School of Law in Boston. “I had to make a decision about bar exams even before I graduated because the deadlines to apply differ from state to state,” she says. “That didn’t give me time to really evaluate my situation, but I figured my odds were better in the employment market if I took the bar in both Illinois and Massachusetts.”

Over a 72-hour period in July, Gallagher took the six-hour essay exam on Illinois law, then took the six-hour multistate exam the next day. After finishing, she went straight to the airport to catch an evening flight to Boston so she could take the Massachusetts essay exam the next day.

“It was a fun three days with a flight in between,” says Gallagher, who was notified recently that she passed the bar in both states.

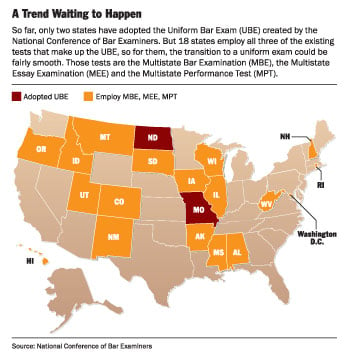

Earlier this year, Missouri and North Dakota became the first two states to adopt the uniform bar exam, which was developed by the national conference with input from the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar and others in the field. Both states will offer the UBE starting in February 2011.

“Some view it as a significant change, but we didn’t see it as significant,” says Kellie R. Early, who was executive director of the Missouri Board of Law Examiners earlier this year when the state supreme court adopted the uniform bar exam and who now serves as director of administration at the NCBE. “Somebody has to jump in the pool first. We saw it as the right thing to do—and the right direction for the profession to move.”

A CRITICAL YEAR

Adding to the momentum, the Conference of Chief Justices endorsed the concept of a uniform bar exam in a resolution adopted during its annual meeting in late July. Less than two weeks later, a similar resolution was adopted by the council of the legal education section during the ABA Annual Meeting in San Francisco. Both resolutions urge bar admission authorities “in each state and territory to consider participating in the development and implementation of a uniform bar examination.”

So far, the resolution expresses the position only of the section, says Jerome C. Hafter, who was chair when the council took its action during the summer. But the section expects to submit the measure for consideration in 2011 by the ABA’s policymaking House of Delegates, says Hafter, a partner at Phelps Dunbar in Jackson, Miss.

Meanwhile, several states are closing in on decisions to adopt the UBE, Moeser says. “Next year will be critical in determining if the engine kicks over and starts running,” she says. “The idea is less radical the more you live with it.”

The UBE is drawing more interest at a time of some uncertainty over the future of legal education and licensing. The legal education section, for instance, is likely to consider changes in its accreditation standards for law schools that emphasize “output” measures of practical legal training that students can apply in actual practice settings.

At the same time, bar admissions issues are part of the agenda for the ABA Commission on Ethics 20/20, which is charged with studying legal ethics issues relating to advances in technology and increasing globalization.

“There are so many issues on the table that there is some confusion about what’s going on in admissions,” says Gerald W. VandeWalle, chief justice of the North Dakota Supreme Court and a member of the Ethics 20/20 Commission. “The uniform bar exam is just part of that.”

Many states already have at least some pieces of the uniform bar exam in place.

As conceived by the National Conference of Bar Examiners, the UBE is made up of three separate tests that would be administered over a two-day period: the multistate bar exam, which already is used by the District of Columbia and 48 states; the multistate essay exam, which is used by 23 states and the district; and the multistate performance test, in use in 31 states and D.C. Eighteen of those jurisdictions already use all three of those tests.

Under a uniform bar exam, states would continue to play a prominent role in determining who will be admitted to practice by setting requirements to take the bar exam, setting the scores necessary to pass, conducting character and fitness reviews of candidates, and deciding whether to continue to require candidates to be tested on local law.

Those testing options range from adding a segment to the UBE that focuses specifically on the law of the jurisdiction, to the equivalent of a mandatory continuing legal education program for newly admitted lawyers, or to what some call the “driver’s license” approach, in which candidates may continue taking a short test on the basics of local law until they pass.

“A lot of prerogatives will still reside in the states,” Moeser says. But others say concerns about whether states might lose control over bar exams and admissions is a key reason why there may be some reluctance to jump on the UBE bandwagon.

WHITHER THE STATE?

When the North Dakota Supreme Court adopted the UBE, it decided to go without any element that tests candidates on state law, says Chief Justice VandeWalle, a past co-chair of the Bar Admissions Committee in the ABA’s legal education section. Still, he says, “I had a pang of ‘Oh, boy, there goes the last stamp of North Dakota on the bar exam.’ There is local pride, local culture.”

Missouri also had to decide what to do about testing on local law, Early says. The supreme court wanted to retain an element that would test candidates on state law, and the board of law examiners determined that some form of the CLE approach would be most appropriate. The board created a short on line test that allows candidates to refer to CLE materials specially produced to help them identify distinctive elements of Missouri law.

“The point is to make the candidates look at the materials,” says Early. “We felt that was all that was necessary, given the law in Missouri.” Meanwhile, she says, “we felt the instruments in the UBE adequately test whether a candidate has minimum skills to practice law.”

Hafter says the overall quality of the UBE as a testing mechanism should be a primary factor for states considering whether to adopt it.

The advantage of taking one bar exam “isn’t new to the modern period,” Hafter says. “All of those arguments have been outstanding for some time, although they have been highlighted recently during the recession.” But, he says, “the UBE is a better bar exam than any state can prepare on its own. That’s really the core reason for having it.”