Law Job Stagnation May Have Started Before the Recession--And It May Be a Sign of Lasting Change

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The legal profession is undergoing a massive structural shift—one that will leave it dramatically transformed in the coming years.

There’s no doubt that the financial crisis beginning late in 2007 was for most lawyers a game-changer, prompting drastic measures as firms laid off thousands of associates, de-equitized partners, and slashed budgets and new hires.

But many hoped—and still do—that the effects of the recession would ebb, and that the profession, which had just witnessed a golden age of prosperity unmatched by any other industry, would re-emerge relatively unscathed.

The golden era is gone, but this is not because the law itself is becoming less relevant. Rather, the sea change reflects an urgent need for better and cheaper legal services that can keep pace with the demands of a rapidly globalizing world. The Great Recession—a catalyst for change—provided an opportunity to re-examine some long-standing assumptions about lawyers and the clients they serve.

Whether BigLaw lawyers, boutique specialists or solo practitioners, U.S. lawyers can expect slower rates of market growth that will only intensify competitive pressures and produce a shakeout of weaker competitors and slimmer profit margins industrywide. Law students will find ever-more-limited opportunity for the big-salary score, but more jobs in legal services outside the big firms. Associates’ paths upward will fade as firms strain to keep profits per partner up by keeping traditional leverage down.

And those who wish to rise above the disruption will have to deal with technology that swallows billable work, a world market that takes the competition international, and a more sophisticated corporate client with vast knowledge available at the click of a mouse.

NO HISTORY

The biggest problem affecting U.S. lawyers is a failure to understand the origins of our own success. For nearly a century, industry after industry underwent dramatic transformation while lawyers continued to ply their artisan trade. Many lawyers prospered under this conservative path because the substance of what they did was too important to an increasingly complex, interconnected economy.

No more. As the balance of power shifts from traditional law firms and toward clients and a raft of tech-savvy legal services vendors, the price of continued prosperity for lawyers is going to be innovation and doing more with less.

Law touches on virtually every aspect of our social, political and economic lives. As the world becomes more interconnected and complex, new legislation, regulation and treaties bind us all together in ways that promote safety, cooperation and prosperity. Not surprisingly, over the last 25 years government data shows legal services constitute a slightly larger proportion of the nation’s GDP—now nearly 2 percent—with no hint of decline.

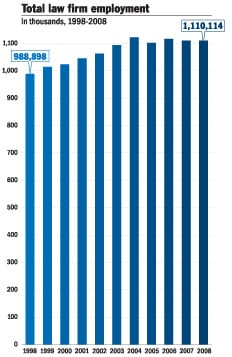

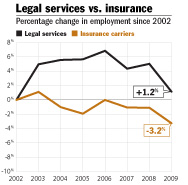

However a very different piece of evidence is the change in total law firm employment, or lack thereof. According to payroll data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau, the multidecade surge in law firm employment hit a plateau in 2004. Between 1998 and 2004, total law firm employment grew by more than 16 percent, or 169,000. Yet between March 2004 and March 2008, several months before the Wall Street meltdown that initiated an unprecedented wave of law firm layoffs, the nation’s law firm sector had already shed nearly 20,000 jobs.

This is a drop in the bucket for an industry that employed more than 1.1 million workers in 2004. But the flattened number of law firm jobs occurred at the same time major law firms in large urban areas were in a bidding war, taking entry-level salaries from $125,000 to $145,000 to $160,000. The public dialogue in the legal press and blogosphere was so fixated on the rising profits per partner at the nation’s top 100 law firms that the broader, systemic patterns went largely unnoticed—at least until the financial fallout descended in the fall of 2008.

By overgeneralizing how well the big firms were doing, we failed to notice a slow but fundamental economic shift affecting the majority of lawyers, who are solo practitioners or in small-to-medium-size law firms.

According to Fred Ury, a former president of the Connecticut Bar Association and a trial lawyer based in Fairfield, Conn., those mainstream lawyers had been feeling the pain for a while.

“The biggest problem,” says Ury, “is that ordinary citizens cannot afford to hire a lawyer. The bread and butter of small firm practices are criminal defense work, wills and trusts, leases, closings and divorces. Yet in Connecticut, 80 to 85 percent of divorces have a self-represented party because most families can’t afford to hire one lawyer, let alone two. Nearly 90 percent of criminal cases are self-represented or by a public defender because families can’t scrape together a retainer.”

Ury, who has practiced in a small firm for nearly 35 years, predicts the problem of unmet legal needs, if not solved by lawyers, “will be solved by technology.”

Source: The American Lawyer.

LEGAL, NOT LAW FIRM

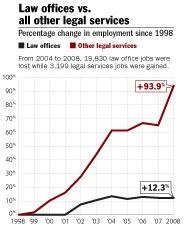

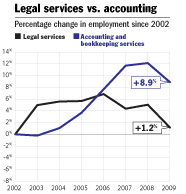

The relative high price of legal services creates opportunities for new entrants. Although law firm employment declined from 2004 to 2008, 3,200 jobs were added in all the other legal services categories, which include U.S. jobs with legal process outsourcers and agencies for contract attorneys. But in 2008 the average law firm employee made an average of $79,500 versus $46,800 for a worker in the other legal services groups—and this doesn’t count the wages of foreign outsource workers.

Novus Law is one of the new breed of legal services vendors that combines sophisticated technologies and work processes with an international workforce that operates 22 hours a day. The company specializes in electronic document review for large-scale litigation and corporate due diligence for large businesses. To ensure delivery of a virtually error-free work product on time and within budget, Novus Law engineered an intricate, metric-driven work process certified by Underwriters Laboratories.

Ray Bayley, president and chief executive officer of Novus Law, also perceives a structural shift.

“I think the legal profession has been defined as 250 law firms and lawyers that are licensed to practice law,” Bayley says, “but I view the entire profession as an industry. Over the last 20 to 30 years, virtually all industries have undergone enormous structural change because of globalization and technology.

“The changes affecting the legal services industry began in the late 1980s. They have been significantly accelerated by the recession, and it’s picking up pace. In five years, the profession will be very different.”

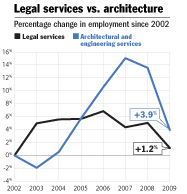

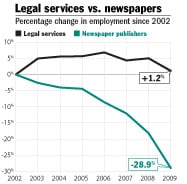

To date, the depth of economic dislocation for U.S. lawyers has been relatively mild, at least when compared to workers in other industries. Manufacturing is the most obvious example, but professions such as advertising, journalism and travel also have been wracked by massive structural changes affecting employment, wages and professional autonomy.

In contrast, total employment in the legal services industry has closely tracked the steady growth rate of government for the past 25 years, with only slight diminution during economic recessions. Yet, from 2006—two years before the financial meltdown—to 2010, employment in legal services began to diverge much more sharply from government.

New economic realities are affecting even the nation’s largest firms. Press releases may still report higher profits, but since 2007, revenue-per-lawyer figures have been trending sideways or down for the majority of the Am Law 100. Like the overall employment numbers for law firms, the stagnation represents a sharp break from historical patterns.

Lower revenue averages indicate slower rates of market growth, intensifying competition, shakeout and slimmer profit margins.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

HOW WE GOT HERE

Over the last century, the traditional associate-partner law firm model has been one of the most enduring features of the U.S. legal profession. However, this remarkable run was made possible by a set of extraordinary economic conditions that no longer prevail.

In the early 1900s as the great industrialists and financiers built their empires, there was a shortage of sophisticated business lawyers. As law firms recruited apprentices on a larger scale to keep pace with business needs, a new question arose: Once the student became the master’s equal, how should the profits be divided?

The most famous solution came at that time from Paul Cravath, who founded the elite New York City law firm of Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Cravath recruited top graduates from leading law schools and developed their skills and acumen through a rotation system that lasted several years. The stated purpose of the Cravath system was to create “a better lawyer faster.”

Dubbed “a law factory,” Cravath’s firm was able to handle prodigious volumes of work and simultaneously train sophisticated business lawyers. As associates ascended into the higher echelon of the firm, the most lucrative reward was partnership. Those who failed to make partner there found the firm’s excellent training opened doors at other New York City firms. Unlike its competitors, the Cravath firm was stable and had the ability to scale its growth to meet the escalating needs of its clients.

Virtually all business law firms in major cities organized themselves along similar principles in the years that followed—growing and prospering from the post-World War II economic boom. Many of these firms emerged as today’s elite brands on either a regional or national level.

But the U.S. legal profession no longer has a shortage of sophisticated business lawyers. Increasingly, clients have become comfortable pitting one firm against another to obtain pricing discounts, and many large corporate clients no longer want to pay the billing rates of junior associates who are learning on the job, excluding first- and second-year associates from working on their matters.

In response, law firms have reduced the number of entry-level lawyers, turning the traditional pyramid structure into a diamond with many senior associates and nonequity partners composing the broad middle. While that makes sense in theory, if the entire industry attempts to shed the training costs of entry-level lawyers, it will eventually produce a shortage of midlevel attorneys and higher labor costs to stave off unwanted attrition. It will also produce a general graying of the corporate bar—a trend evident in much of the Northeast—that will stifle firms’ ability to innovate.

In many respects, the short-term needs of established law firms to generate higher revenue and profits to retain the firms’ biggest rainmakers are at odds with long-term needs to invest in a more sustainable business model tied to the changing demands of clients. The sheer size and geographic dispersion of many firms, along with the limited time horizons of their current partners, make change unlikely. Yet as firms resist change, their clients become more likely to vote with their feet: taking more work in-house, experimenting with smaller-market/lower-cost firms or giving work to legal process outsourcers, all of whom have greater flexibility to innovate.

The 21st century is sure to give rise to a new generation of legal entrepreneurs who create novel ways to adapt to the needs of clients. Successful innovators will grapple with the three interconnected forces that make change inevitable:

1) More sophisticated clients armed with more information and greater market power to rein in costs.

2) A globalized economy, which increases the complexity of legal work while exposing U.S. lawyers to greater competition.

3) Powerful information technology that can automate or replace many of the traditional, billable functions performed by lawyers.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

IN-HOUSE RULES

Perhaps the group most acutely aware of the drumbeat of change—and striking the tom-tom themselves—are corporate general counsel. Regardless of the size of a company’s legal budget, clients want to control their operating costs. And that includes legal services.

Lawyers still possess specialized knowledge only intelligible by studying case law and attending law school. But the overabundance of free, online information has created lawyer-client relationships that are more symmetrical in terms of information. Social networking tools also place the wisdom of crowds at the fingertips of individual consumers. If lawyers are good, clients will find them, but the clients will also find their closest competitors. The tactics needed to win business are thus likely to be more sophisticated and targeted.

In the corporate realm, general counsel are increasingly expected to achieve what other departments and businesses do—get better results at lower costs. No longer viewed as purveyors of the law, in-house lawyers are problem solvers and key business strategists. The multimillion-dollar budgets that flowed unchecked into the coffers of the nation’s largest law firms are now closely guarded and counted.

“There is no question that a serious recession caused a heightened sense of awareness for law firms and consumers,” says Gregory Jordan, who works out of Pittsburgh and New York City as Reed Smith’s global managing partner and chairman of the senior management team and executive committee. “As the recession starts to reverse itself, there will be some movement away from that super-heightened awareness of cost, but this recession gave buyers of legal services enough time to really appreciate that they could get the same quality of service for less than before the recession. The better, faster, cheaper concept is very much here to stay.”

Although most general counsel begin their careers at traditional law firms, they are increasingly influenced by the business practices of their fellow corporate managers. In some cases, this means new procurement practices for legal services, using technology to speed up or automate routine legal tasks, or building in-house expertise that is core to the company’s strategic objectives. When general counsel do turn to outside counsel, they have the ability to pit one law firm against another to achieve competitive rates. And although clients may continue to stay in a long-established relationship with a firm, that doesn’t guarantee they’ll return with new matters or refer colleagues.

General counsel should be careful, however, not to overplay their hands. Although chief legal officers want their outside counsel to have shared risk or “skin in the game,” general counsel who meet their annual budget by pushing for discounted fees are unlikely to get the best long-term results. The key to doing more with less is innovation, often achieved by long-term relationships and shared information. This requires mutual trust and a willingness to share risk over time.

Some Fortune 500 companies have adopted the presumption that all legal work will be done in-house. General Electric’s legal department and others have lawyers in India supervised by in-house lawyers in the U.S. And Cisco Systems built a Web-based knowledge management system that captures email conversations, facilitates secure communication with experts, and documents answers to frequently asked questions—all to boost in-house productivity and cut the law department’s expenses.

On Main Street, while the average baby boomer client doesn’t want to create a will or trust online, 20-year-olds, soon to become the typical legal consumers with families, are so used to conducting their business on the Internet that that’s how they’ll also buy their legal services, says Ury, founder of Ury & Moskow. As Generation Y and Millennials ascend the corporate ladder and amass wealth, will they be just as apt to purchase more sophisticated services online? “Probably not,” Ury says, “but they will come with their own drafts.”

“My clients do that now,” says Ury, adding that clients are more apt to bring a contract or lease for his review rather than request a draft done by his law office.

In the future, Ury predicts, nearly all legal forms and commoditized services will be free of charge. He points to the Connecticut secretary of state’s website, where hundreds of forms are available to download, including divorce petitions and business filings.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

E-LAW

Technology is replacing many of the tasks formerly performed by lawyers. From a social point of view, this is very desirable because it drives down the cost of legal services and satisfies unmet legal needs. From an industry view, however, it can be a gut shot to the bottom line.

Incomes of ordinary middle-class citizens have stagnated while the relative price of legal services has risen. Unmet legal needs are on the rise, opening the door for inexpensive, Web-based legal services providers that essentially offer do-it-yourself kits for many personal or business legal needs.

One such provider, LegalZoom, has had more than 1 million customers in its 10 years online. The Practical Law Co. has created a similar line of form documents and annotations that deal with many of the most sophisticated transnational and compliance issues facing large corporate legal departments. And Cybersettle claims it has resolved more than $1.6 billion worth of cases in the last 10 years.

Using technology to tap into the mass consumer or business market, however, requires more than a great idea. Also necessary are access to capital and the ability to collaborate with professionals in other disciplines, such as system engineering, knowledge management, marketing, finance and project management. Few lawyers have the time, financial wherewithal or risk tolerance to play in this league.

For most lawyers, survival will depend upon their ability to harness technology to deliver greater value to clients at a cost that declines—yes, declines—over time. The biggest challenge for law firms will be transitioning away from internal firm metrics that reward billable hours and discourage or prohibit the crucial trial-and-error experimentation needed to create, refine and market more innovative work processes that do more with less.

At a minimum, law firms need to return to the concept of sharing risk among the equity shareholders and retaining earnings to finance new technologies, training, and research and development.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

GLOBALIZATION

Moving forward, globalization represents both the greatest challenge and greatest opportunity for lawyers.

As the world becomes more interconnected, business relationships rarely will stop at national borders. Basic family law issues will inevitably bump up against immigration law. Sales of goods and services over the Internet raise complex issues of international tax. Exploiting and protecting the value of any domestic innovation requires a strong grasp of international intellectual property law. A client who opens an office or facility in a foreign country faces a dizzying array of legal issues that must be quickly and efficiently analyzed before a business decision can be made.

The flip side of this business opportunity, however, is that few clients have the ability or willingness to pay for this service under the traditional law firm model. It is either too slow, too expensive or too unpredictable. Globalization exposes clients to an international workforce that is often hungrier and completely unwedded to past practices.

As the global economy matures, the push for increased regulation will also boost demand for sophisticated business lawyers. This has a twofold effect: Prominent U.S. firms, specifically among the 250 largest firms, are expanding global operations—a costly venture that will be unobtainable for some. And U.S. lawyers, particularly young associates and freshly minted law school graduates, face fierce competition for work from overseas counterparts.

“The goal of clients in big cases is to play it safe,” says William Reynolds, a professor at the University of Maryland School of Law. “And playing it safe is to hire the best lawyers—and those aren’t in India.”

But what if, in the coming years, they are?

U.S. lawyers underestimate the threats of foreign competition to the provision of domestic legal services. The realm of “all other legal services providers,” which grew from less than $1 billion in total revenues in 1997 to nearly $3 billion in 2008, will continue to attract sophisticated business capitalists eager to obtain a greater portion of U.S. corporations’ legal budgets.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Lower-level “commodity” legal work is already being sent to developing markets like China, India and the Philippines because wages are lower and the multiplying workforce is eager. Staff positions doing document review and slogging through discovery are highly coveted by a booming, educated middle class in a culture where law firm jobs often go to those at the top of the caste system. And quality, consistency, security and efficiency concerns have been quelled by legal services providers such as Pangea3 (acquired by Thomson Reuters), which is building facilities across the U.S. modeled after its India operations, and Chicago-based Mindcrest, which has facilities in India.

In fact, quality control is an easy concern to eliminate when working on large-scale projects for corporations because of the rigorous methodology and processes employed, which law firms often overlook, according to Ganesh Natarajan, Mindcrest’s co-founder, president and CEO.

As a result, these facilities become the perfect laboratories for developing more sophisticated legal work processes. Akin to the Japanese car manufacturers who started with cheap economy cars in the 1970s and eventually created the brands that challenged Cadillac and Lincoln, foreign legal workers are destined to become a formidable economic force.

For those firms at the apex of the profession, the pressures of change may not be felt as heavily as by their midlevel counterparts, causing some law firm leaders to doubt the magnitude of the tremors affecting the industry.

“I’ve seen various waves of purported reform crash on our shores,” says Peter Kalis, chairman and global managing partner of K&L Gates. “I see no paradigm shift in the business of law. What I see are evolutionary adaptations to changing market conditions.”

Even so, Kalis says his firm’s aggressive global expansion in recent years is the result of client demands for cross-border expertise—and firms that can’t meet those demands could fail.

“In a world where even modest-size clients compete in global markets, they are going to need law firms positioned to address that,” says Kalis, who works out of the firm’s New York City and Pittsburgh offices. “There will be a lot of casualties among firms not on the right side of history, and they will be the last to know until talent and clients start to migrate to other firms.”

Whether the changes affecting the legal profession are indeed a reflection of market cycles or a complete paradigm shift will become evident in coming years. But for those betting substantive change has not happened, they are betting their practices against the future.

William D. Henderson is director of the Center on the Global Legal Profession, and professor of law and Nolan Faculty Fellow at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law. He received his JD from the University of Chicago in 2001. Rachel M. Zahorsky, a lawyer, is a legal affairs writer for the ABA Journal. She can be reached at [email protected].