U.S. Lags Behind Other Wealthy Nations in Rule of Law Index

Preliminary versions of the Rule of Law Index already had signaled that its final report would not be encouraging for the U.S. justice system. But the results in the official version of the index released Oct. 14 still paint a surprisingly stark picture of this country’s standing compared with other advanced nations when it comes to incorporating principles of the rule of law.

The report, produced by the World Justice Project—a 3-year-old initiative sponsored by the ABA and a number of other organizations representing various disciplines—indicates that the United States lags behind other highly developed nations on all but one of nine key measures of adherence to the rule of law.

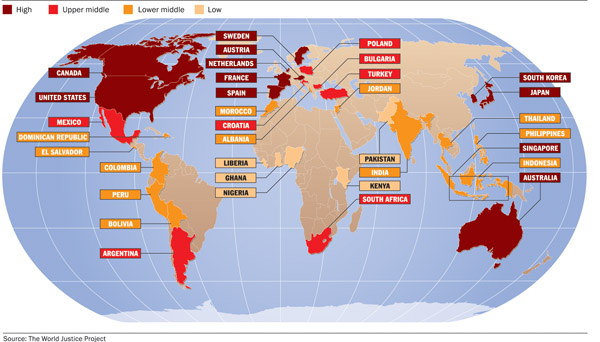

Countries Grouped by Income Level

The findings for each country in the index are based on surveys of some 1,000 residents in its three largest cities, as well as input from experts in the law and other disciplines.

The index was released at briefings in Washington, D.C., where leaders of the World Justice Project described it as an important new tool for measuring the extent to which different nations adhere to the rule of law and identifying areas where they can focus efforts to improve.

“This kind of tool is most important,” said Ellen Gracie Northfleet, a former chief justice of Brazil who serves on the World Justice Project’s board of directors. “We can exchange our intuitive knowledge of what’s wrong and right with measurable data.”

The project is a multidisciplinary effort to strengthen the rule of law around the world. It was founded by William H. Neukom of San Francisco, who served as ABA president in 2007-08. In addition to producing the index, the project sponsors outreach meetings worldwide, provides seed grants for on-the-ground programs and supports new scholarship efforts in the field. The project originally operated with extensive logistical and staff support from the ABA but is now an independent not-for-profit corporation.

WE’RE NOT NO. 1

Every major region of the world is represented in the index. Peer groups of nations are categorized in the study on the basis of income level and region, but not form of government. The United States is part of the 11-nation high-income group and seven-nation Western Europe and North America regional group.

The good news for the United States is that it ranks no lower than 11th among the 35 countries covered by the index on any of nine key principles. However, when compared with its high-income and regional peers, the United States ranks at or near the bottom in nearly all of those categories. The other nations that make up the high-income group are Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Japan, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, Spain and Sweden. The Western European nations and Canada are included in the regional group with the United States.

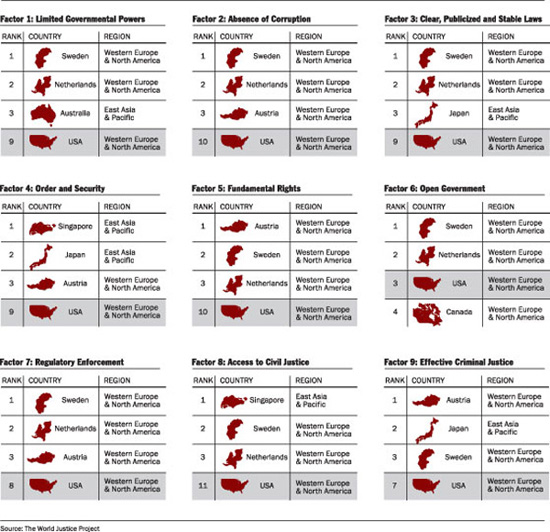

Seven of the 11 nations in the high-income group rank in the top three on at least one of the rule of law factors identified by the World Justice Project. At the top is Sweden, which received eight top-three rankings, followed by the Netherlands (seven), Austria (five), Japan (three), Singapore (two), and Australia and the United States (one each).

Significantly, the United States ranks last within both its income and regional groups on providing access to civil justice, which the index measures primarily on the basis of whether citizens believe they can bring their cases to court and whether representation by lawyers and other legal professionals is available and affordable.

Those rankings are reinforced by the scores that the United States received for access to justice in both civil and criminal cases. Using a formula that identifies specific elements of access to justice, the index produced a score for each country, ranging from a low of 0 to a high of 1. Each country received a score for every one of the nine rule of law factors.

The United States received a score of 0.66 for access to justice—the lowest score for any country in the high-income group. The next lowest score was 0.68, for both France and Japan. The highest access score was 0.83, received by both Singapore and Sweden. The average score for access was 0.76. The United States scored farther below the average among its peer countries for access to justice than for any other rule of law factor. And a few countries in other income groups—including Colombia, Poland, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey—had scores just below the United States.

Those findings from the Rule of Law Index come as one more dose of bad news for a U.S. justice system already being pummeled by the Great Recession. Access to civil justice services already is a growing concern in the United States as recessionary pressures have caused many states to reduce funding for their court systems. In some jurisdictions, courthouses have been closed, or hours cut back and trials limited. Meanwhile, the Legal Services Corp. uses data from the most recent U.S. census to estimate that nearly 57 million Americans—the highest number ever—now qualify for assistance from local legal aid programs. (The LSC supports those programs with funding from Congress.) Other studies estimate that legal aid offices and pro bono efforts by private attorneys meet only about 20 percent of the civil legal needs of poor Americans.

In one of his first actions after becoming the ABA’s new president in August, Stephen N. Zack appointed a Task Force on the Preservation of the Justice System to focus on how the recession is affecting access to justice for Americans. “Overall, the U.S. legal system is among the very finest in the world, and many others look to our legal system when it comes to best practices in their own countries,” says Zack, who is administrative partner at Boies, Schiller & Flexner in Miami. “But the index points to the fact that we have much important work to do, including in the area of making our legal system more accessible to people of all walks of life.”

Meanwhile, efforts to gain recognition for the principle that every person is entitled to representation by a lawyer in civil cases where basic human needs are at stake have sputtered. To date, no state legislature or court has recognized a sweeping right to counsel in civil cases, although 14 states have begun to look at how such a guarantee might be implemented. In August, the ABA House of Delegates, which in 2006 endorsed a right to counsel in vital civil cases, adopted two measures that together provide a road map for creating programs that would make state-funded legal counsel available to qualifying low-income people.

HELPING COUNTRIES HELP THEMSELVES

Because the rule of law index is primarily statistical in nature, it does not analyze the causes of each country’s performance on the rule of law factors. “While the index is helpful to tracking the ‘temperature’ of the rule of law situation in the countries under study,” the report states, “it is not powerful enough to provide a full diagnosis or to dictate concrete priorities for action. No single index can convey a full picture of a country’s situation. Rule of law analysis requires a careful consideration of multiple dimensions—which vary from country to country—and a combination of sources, instruments and methods.”

At the briefing that was held to announce the release of the index, William C. Hubbard, chair of the World Justice Project, said, “Everyone in this room wants progress and a stronger rule of law, but we’re not here with a one-size-fits-all approach to improving the rule of law.” Rather, the purpose of the index is to produce data to help each country identify areas for possible reform, said Hubbard, a partner at Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough in Columbia, S.C., who is immediate-past chair of the ABA House of Delegates.

Other representatives of the World Justice Project said the index is an important addition to rule of law studies because it seeks to measure specific elements that define the rule of law on the basis of how they actually apply to the real lives and experiences of people in various countries. “Ultimately, the rule of law isn’t about numbers; it’s about people,” said Juan Carlos Botero, project director for the index.

Botero and Hubbard said the Rule of Law Index released in October will be followed by expanded versions issued on an annual basis. The index should cover 70 countries in 2011 and 100 countries—covering more than 95 percent of the world’s population—by 2012. Publishing the index on an annual basis also will help countries track progress in efforts to bolster rule of law measures.

The ability to “benchmark” progress is an important feature of the index that will help foster “a new mentality,” said Northfleet. “What gets measured gets improved.”

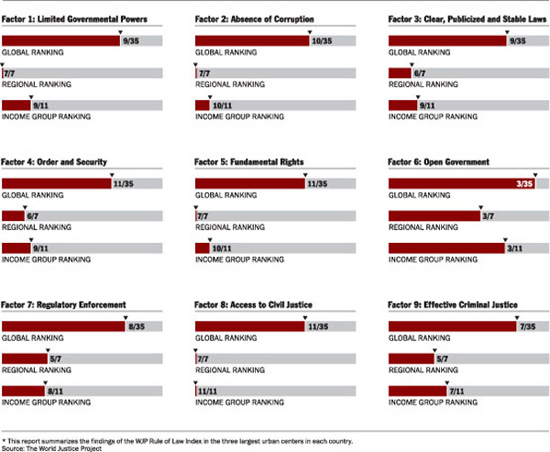

Where the United States Ranks

The U.S. ranks favorably on nine rule of law factors compared to all the nations in the Rule of Law Index, but it still ranks below most of the other nations in its regional and income groups. Lower numbers within each category signify a higher level of adherence to the rule of law.

The Nations at the Top

A small group of nations dominates the top of the rankings for all nine factors in the Rule of Law Index. The United States breaks the top three in only one category.

Sidebar

Formula for Measuring the Rule of Law

The Rule of Law Index seeks to measure a nation’s adherence to rule of law principles by focusing on nine key factors:

Limited governmental powers. What constitutional and institutional boundaries exist for governmental powers, and to what extent are government officials and agents held accountable under the law? Are there other checks on governmental powers, such as a free and independent press?

Absence of corruption. Do government officials—including police, the military and the judiciary—largely refrain from such things as bribery, improper influence from public or private interests, and misappropriation of public resources?

Clear, publicized and stable laws. Are laws written and disseminated in a way that helps the public understand them?

Order and security. How secure are people and property, particularly in the context of crime, terrorism and political violence? To what extent is the use of violence an acceptable means to redress personal grievances?

Fundamental rights. Does the government recognize core human rights by recognizing equal protection under the law; freedom of thought, religion and expression; freedom of association; the right of privacy; and rights of the accused? Are there prohibitions against forced and child labor, as well as limits on retroactive application of criminal laws?

Open government. Is the lawmaking process open to the public, and does it provide opportunities for diverse viewpoints to be heard?

Regulatory enforcement. Are administrative proceedings open to the public, and are regulations enforced with an absence of improper influence by public officials or private interests? To what extent does the government take private property without adequate compensation?

Access to civil justice. Are citizens able to resolve their personal grievances without resorting to violence or self-help? Are citizens aware of the remedies available to them, and is affordable legal advice available to them? Are there excessive fees and procedural barriers to courts and other dispute resolution mechanisms?

Effective criminal justice. Is there a system in place capable of investigating and adjudicating criminal cases effectively and impartially, and are rights protected?

Source: The World Justice Project