Features

Privatized probation becomes a spiral of added fees and jail time

Tom Barrett’s legal odyssey began with an arrest for stealing a $2 can of beer, which led to a lengthy and costly encounter with a private probation outfit.

His expertise did not lend immunity to certain pitfalls. Barrett grew addicted to a steady supply of opioid painkillers Army doctors gave him for lower-back pain, though eventually the problem turned out to be kidney stones, which were blasted away with shock waves.

But the pill-monkey remained on his back. Barrett, 53, battled it for years, supplementing with alcohol. After a 2007 car crash—sober and no drugs, blood tests would show—in which he suffered multiple skull fractures that left him in a coma, Barrett lost grasp on the fragile normalcy he'd managed to maintain as a husband and father of three now-grown men.

He wound up divorced, homeless and broke, and in April 2012 he was arrested for stealing a $2 can of beer from an Augusta convenience store. Though not sentenced to time behind bars, his inability to pay a $200 fine would lead to him cycling in and out of jail, initially for almost two months, despite the fact that U.S. and state constitutional protections prohibit such punishment.

Someone with means would have walked out of the courtroom free. Barrett entered modern-day debtors' prison.

For stealing the single can of beer, a different kind of monkey attached to Barrett's back—privatized probation, the increasing and increasingly controversial outsourcing of such services for those convicted of misdemeanor offenses. The companies have argued that they provide professionally trained supervision and follow the courts' direction.

The judge put Barrett on 12 months' probation during which Sentinel Offender Services, based in Irvine, California, would supervise him and collect the fine in installments. But after nearly a year, he was still on the hook for payments, owing Sentinel over $1,000 in fees, more than five times greater than the fine itself.

"I was so depressed I'd taken the beer and told myself I gotta make it through the 12 months and take care of it," Barrett says. "But it was like a curveball when they said I had to wear a leg monitor."

Barrett couldn't pay an $80 startup fee Sentinel demanded for an electronic ankle-bracelet monitoring device and, at the company's request, was jailed for nearly two months. An Alcoholics Anonymous sponsor finally paid for it, but Barrett couldn't make the $360 monthly monitoring fee, plus nearly $40 in monthly probation fees, as well as court payments. He subsisted on food stamps and a small cash income from selling his blood plasma. Twice-weekly bleedings brought in nearly $300, but going without food to try to satisfy the debt lowered his blood protein level so much that it was no longer good enough to sell.

Last September, Sentinel was ordered to cease some of its key practices in two Georgia counties. Among other things, Superior Court Judge Daniel Craig ruled in Tennille v. Sentinel Offender Services and similar cases before him that statutory law does not permit the extension of probation beyond two years, a practice known as tolling, and under which some probationers have had arrest warrants over their heads for as long as eight years so the company could get paid. In addition, Craig ruled that the law does not allow the use of electronic monitoring for misdemeanors. Barrett is a plaintiff in one of two batches of Craig's cases from Richmond and Columbia counties, both of which are on appeal and cross-appeals at the Georgia Supreme Court.

Photo of Sharon Dolovich by Jonah Light

OFFENDERS MUST PAY

The issue of private probation has become the hottest flashpoint on a firecracker strand of "offender-funded" justice that has been steadily increasing for a couple of decades, particularly since the economy soured in 2008. Several private lawyers as well as public interest groups such as Human Rights Watch, the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Southern Center for Human Rights, the Brennan Center for Justice and the American Civil Liberties Union are targeting outsourced probation more and more.

The efforts are in addition to ongoing challenges of other kinds of debt piled on those brought into the criminal justice system. They can be charged for almost anything imaginable—such as room and board, medical care, haircuts, jail garb, bedding and now, in Anderson County, Tennessee, even toilet paper and feminine hygiene products.

There are signs of high-level pushback. Ohio's chief justice recently put an end to the widespread practice of jailing people for costs and fines, which are civil matters. In May, Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper signed legislation that forbids such incarceration except in some cases in which nonpayment is willful.

Both initiatives resulted from investigations and reports by state ACLU affiliates. Similar efforts have not yet been availing in some other states, such as Michigan and Washington.

These pay-for-jail and pay-or-be-jailed efforts "are all part of a grab bag of strategies to squeeze more revenue from offenders," says Sharon Dolovich, a professor at UCLA School of Law. "We don't want to pay the costs of our own criminal justice system; we want to externalize it all."

So much so, argues a growing legion of critics, that various state and federal statutes and constitutional safeguards have been ignored as citizens are jailed for what amounts to civil debt—and not just in private probation matters—when it simply concerns money owed the court. Even where statutory and constitutional protections prohibit incarceration of indigents for nonpayment, judges in a system where it has become customary still do so. And they do so without determining—as is usually required by law—whether the nonpayment is willful (meaning the person has the wherewithal) and without providing them legal representation when facing jail.

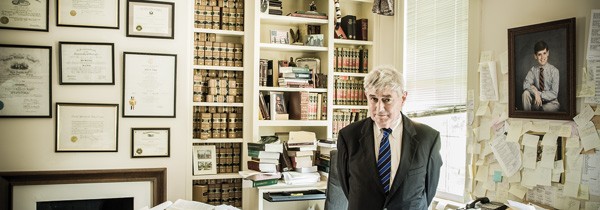

"There's no sliding scale, there's no indigency test—nothing," says John B. "Jack" Long, a 68-year-old lawyer with the Tucker Long firm in Augusta who represents Barrett and 12 others in the two cases Sentinel has appealed, and in which Long cross-appealed a facial challenge to the private probation statute itself.

Long's typical portfolio of bankruptcy and domestic relations cases lent a useful understanding of certain problems facing people hamstrung by financial issues when he was asked, in 2008, to take a private probation case pro bono. He ended up going to war.

Attorney John B. "Jack" Long now represents Tom Barrett. Photo by Stan Kaady.

Georgia is one of more than a dozen states, including Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Tennessee and Utah, that have privatized probation for misdemeanors. The industry's pitch caught on with court systems looking for ways to save money and ensure collection of what they're owed: You pay us nothing; we supervise them and collect revenues for you.

More and more towns and cities are looking to save money—and make money. Thus, even tiny places with courts not-of-record can turn their jurisdictional claim to as little as a mile of major road into significant revenue from traffic tickets. In states that permit private probation, the companies become, in effect, collection agencies for the courts, routinely holding the threat of arrest over the heads of those who can't pay.

"Mayors think it's a great deal because they can get a new fire truck," says G. Daniel Evans, a Birmingham, Alabama, lawyer pressing several lawsuits against the Georgia-based Judicial Correction Services. JCS, along with Sentinel, is a major player in the industry. "They never look down the road where constitutional precepts are being trampled," Evans says.

The ABA Journal reached out to Sentinel, JCS and the Private Probation Association of Georgia for response and comment. All did not respond to interview requests.

For example, Harpersville, Alabama, with a population of 1,620, is a notorious speed trap. In July 2012, Shelby County Circuit Court Judge Hub Harrington ruled in Burdette v. Harpersville that the town's municipal court and JCS were extending probation beyond statutory limits and charging "unconscionable fines and fees," developing what "could reasonably be characterized as the operation of a debtors' prison."

It was, the judge added, a "judicially sanctioned extortion racket."

"The strong wording in his order got something going," says Kevin R. Garrison, an associate in the Birmingham office of Baker, Donelson, Bearman, Caldwell & Berkowitz who has been working pro bono on the Harpersville case with plaintiffs lawyers. "It caught people's attention, which is the best thing that could have happened here in Alabama."

Harrington, now retired, effectively took control of the municipal court, and less than a month later the town dissolved it. The state attorney general's office seized the court's records in an ongoing criminal investigation; fines and outstanding probation-violation warrants for 930 people were dropped, and the class action that was before Harrington is still pending on the issue of damages against the town and JCS, awaiting any possible prosecution.

Photo of G. Daniel Evans by Leigh Ann Photography

WHO RULES?

On paper, the courts wield all authority while directing and supervising the private probation companies. The practical reality of that is under serious challenge through a growing number of investigations by public interest groups, as well as private lawsuits, especially in Alabama and Georgia.

In more fallout from the Harpersville fiasco, the Judicial Inquiry Commission, an arm of the Alabama Supreme Court, issued an advisory opinion in March concerning municipal court judges and private probation. Among other things, it said the court should prevent the companies "from creating the perception" that they have authority over terms and conditions of probation. And judges, not the companies, should determine who is and is not capable of paying.

Those are key points in the argument that private probation companies have direct conflicts of interest because the need to make a profit can override the pursuit of justice.

Recognizing that many of the courts have part-time judges using staff employed by the municipality and meeting only once or twice a month, the Judicial Inquiry Commission wrote that it still remains the judge's responsibility "to enforce the constitutional rights" of those who appear in court. It also expressed concern that municipal judges be aware "that blank orders are never signed by the judge to be filled in by staff; that execution of such orders not be delegated to staff by use of signature stamps."

In other words, the advisory opinion recognized that private probation companies sometimes were exercising authority belonging solely to the court.

In Georgia, a state performance audit report issued in April found that "courts provided limited oversight of provider with contracts that often lack the detail needed to guide provider actions." In addition, some of the private probation companies' "reporting and payment policies were likely to increase probationer noncompliance."

FOLLOWING THE MONEY

In a way, the Georgia statute authorizing private probation was itself the result of a crime.

The most persuasive lobbyist for legislation in 2000 that opened the door to private probation was a prominent public official with pertinent expertise, Bobby Whitworth, chairman of the Georgia Pardons and Parole Board and a former director of the state's prison system. It would turn out Whitworth had profited from his efforts: He was convicted of public corruption for taking $75,000 as a state official to lobby for the legislation, and the money came from the owner of a company called Detention Management Services.

The DMS co-owner who gave him the money, Lanson Newsome, was not charged because it is not illegal to make that payment—just to receive it. Whitworth served six months in prison with 4 years suspended, which he would serve on probation.

The 2000 legislation shifted responsibility for misdemeanor probation to the localities, giving them the option of creating their own probation departments or (as already allowed but little used because the state had been providing services) outsourcing it. Most were eager to avoid significant new budget items and thus were open to the deals offered by private probation companies. Now 85 percent of the state's courts contract out for the services.

DMS was sold for $8.2 million two months after the law went into effect. The buyer was Sentinel Offender Services, whose largest corporate footprint now is in Georgia.

This year, once again, money swirled around the Georgia General Assembly in the form of lobbyists for the private probation industry. They were drawn by a legislative proposal that might cap various fees and have probation companies give notice before getting arrest warrants for nonpayment, and require them to disclose how many probationers they supervise, and the amounts of various fees, charges and other financial information.

But, as sometimes happens with heavily lobbied issues, the proposal morphed into its exact opposite. The bill was crafted in such a way that it would overturn Craig's ruling against extending probation periods and requiring electronic monitoring, and augmented with what critics would consider additional gifts to the industry.

According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, a Sentinel official said in a deposition last summer that the company paid $500,000 to an Atlanta lobbying firm, and that it had gotten new lobbyists for the legislative battle this year. There was also a glimpse of the company's income provided in a document in Sentinel's lawsuit against its risk insurer: The company reported that nationwide in its various enterprises, for the single month of June 2012, it had gross revenue of $5.5 million and net revenue of $1.8 million.

Apparently so much money passed through that an accountant named Steven Hagstrom, Sentinel's controller for 10 years, thought he could get away with embezzling $3.3 million. He was indicted in April and quickly entered a plea bargain with federal prosecutors in Santa Ana, California, requiring him to speak with them about other matters.

Also in April, the Georgia General Assembly passed HB 837, which would allow electronic monitoring for misdemeanors; permit tolling probation periods so probation fees can be paid in their entirety; and establish privacy protections for the companies' financial information.

Sentinel has taken a lot of hits of late: In August 2013, Orange County canceled its contract for electronic monitoring and home detention equipment (a major business for Sentinel), saying the company was guilty of gross negligence in failing to track some probationers. Los Angeles County cited similar problems in an audit in February.

But April was an especially cruel month for Sentinel. Four days after Hagstrom's indictment, Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal vetoed HB 837, citing the lack of transparency if the companies are exempt from the Georgia Open Records Act. Now these issues reside at the Georgia Supreme Court.

COURT CHAOS?

Given the ongoing reverberations, Craig's gavel might as well have been a sledgehammer last September when he ordered Sentinel to cease what he believes to be illegal activities. Some other judges complained that it would create chaos, saying so in a friend-of-the-court brief to him and later when testifying before committees considering legislation that would have undone Craig's ruling.

A month later, the Georgia Supreme Court granted Sentinel's emergency petition to set aside Craig's restrictions on Sentinel pending completion of the appeals and cross-appeals. Long says he hopes the court will deal not just with issues concerning tolling and electronic monitoring but also with the allegation that the statute permitting private probation is facially unconstitutional for reasons of equal protection, due process and excessive fines.He had tried that challenge in 2010, when Long had his first private probation case against Sentinel, filed in 2008, at the high court. In that matter, Sentinel Services v. Harrelson, the Georgia Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling granting a habeas corpus petition. Lisa Harrelson had pleaded guilty to drunk driving—Long says she was under the influence of antihistamines—and a Georgia Superior Court judge found there was no record that she had waived certain rights, including representation by an attorney.

The supreme court upheld the habeas corpus relief, including a requirement that Sentinel repay $500 to Harrelson. On the constitutional questions, Long argued the high court has inherent power to consider them, but the court said it would not because the lower court didn't address them.

But in the cases at the court now, Craig did, so the justices can. Though he savaged certain of Sentinel's practices, the judge stopped short of declaring the statute authorizing private probation unconstitutional. It is "very limited, clear and unambiguous," he wrote, though noting problems with some of the practices carried out by the private companies and the courts. He wrote, for example, that extending probation periods beyond statutory limits by tolling "offends fundamental tenets of due process."

It is for the Georgia Supreme Court to sort out the clashes among statutes, real-world practices and trial court supervision of private probation companies. Can it find a delicate balance of constitutional rights and for-profit provision of criminal justice?

Sidebar

Ohio Chief Justice Maureen O'Connor

Ohio Bans Debtors' Prison Practices

On April 3, 2013, Ohio Chief Justice Maureen O'Connor received a hand-delivered letter and a 23-page research report that were as persuasive as they were alarming: For a long time the state had been running old-fashioned, unconstitutional debtors' prisons, the letter from the Ohio ACLU explained.It would be released publicly the following day.

The day she got it, O'Connor, a former lieutenant governor, dispatched a response via email attachment, asking state ACLU representatives to join her and other stakeholders, such as the Ohio public defender, in a meeting on the matter. It was held at the court two weeks later.

The state ACLU report is heavy on data and analysis based on many days spent in Ohio courtrooms and clerks' offices. Along with big-number statistics from selected counties, it explains the plights of several individuals, with portrait photos, and is titled The Outskirts of Hope: How Ohio's Debtors' Prisons Are Ruining Lives and Costing Communities (PDF).

Though the practice violates both federal and Ohio law, many courts were routinely jailing people for what amounts to civil debts, even if resulting from criminal convictions, often low-level ones—costs, fees and fines owed the judiciary—without determining whether they could pay or bothering to provide legal counsel. Among several examples, the report cited Huron County as "the epicenter of debtors' prison practices in Ohio" for having put 259 people behind bars during a six-month period in 2012 for nonpayment—roughly 22 percent of all people jailed.

"You'd be horrified if Kroger's [supermarket] arrested one of your neighbors for owing $27," says Tim Young, director of the Office of the Ohio Public Defender, who attended the chief justice's meeting. "The only difference here is that the money is owed to the court or county."

With swiftness almost unknown to any big-state, sprawling judiciary, the chief justice set in motion corrective measures that virtually ended the practice within the year. Besides the extensive provision of new training programs, every trial judge received a "bench card" explaining do's and don'ts, with user-friendly encapsulations and graphics. The bench card (PDF) lists the underlying cases and statutes for handling costs and fines. Included are limitations on the widespread use of contempt charges, with which people had been jailed without a determination of ability to pay, which is prohibited by statute.

"We quickly decided what we needed to do to make sure our judges had a handle on this issue," O'Connor says, noting that not all complaints about the practices were valid and not all judges engaged in them, then adding: "The bench card is a good reference, laminated, and will last forever."

O'Connor went one step further on the bench card (to the surprise of those at the ACLU), adding that unpaid fines or costs cannot be a condition of probation, "nor grounds for an extension or violation of probation."

"That was very progressive and very important," says Mike Brickner, an Ohio ACLU lawyer who worked on the report. Though Ohio does not have the more controversial private probation that some states do, court probation offices were sometimes used as collection agencies.

Brickner says the abuses have largely been stamped out and the criminal justice system has adjusted accordingly.

Related Documents:

• Ohio ACLU report: The Outskirts of Hope: How Ohio's Debtors' Prisons Are Ruining Lives and Costing Communities (PDF)

• Bench card (PDF) given to trial judges