Pulse of the Legal Profession

Photos by Patrik Argast.

Web Extras:

Lawyers Who Made the Cover of the ABA Journal

Survey Methodology and More Results

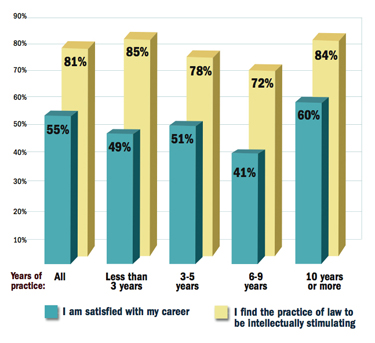

Lawyers agonize about demands on their time. They are concerned about money. And only slightly more than half are satisfied with their careers, according to an exclusive survey of the profession commissioned by the American Bar Association.

But lawyers think the profession is more rewarding than those complaints suggest. Fully 80 percent of the 800 surveyed said they were proud to be attorneys, and 81 percent said they find their practice intellectually stimulating.

The Pulse of the Legal Profession surveyed both association members and nonmembers. The numbers are based on survey responses from 2006. It was the fourth such survey since 2001, and it marked the first time that questions were asked and answered online.

Lawyers expressed their views on a wide variety of issues, including judicial independence, civility among their peers and the quality of law school training. Despite concerns, those surveyed said they expect to remain in the profession; 76 percent reported that they expect to be practicing five years from now.

Here’s a snapshot of the respondents:

TYPE OF PRACTICE

Public sector: 138

Solo: 209

Small firm (2-20 lawyers): 184

Medium-size firm (21-100): 76

Large firm (101+): 97

In-house: 97

YEARS IN PRACTICE

Less than 3 years: 76

3-5 years: 101

6-9 years: 124

10+ years: 499

GENDER

Male: 560

Female: 240

ETHNICITY

White: 654

Nonwhite: 146

Costs Rise, Civility Declines

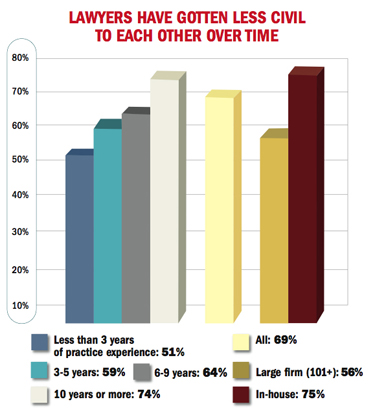

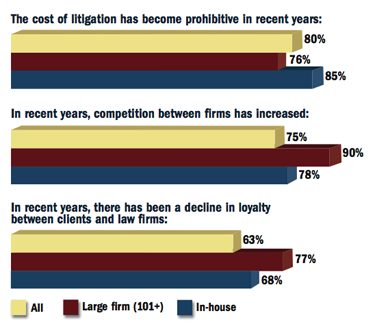

Litigation costs have become prohibitive in recent years, according to the majority of those surveyed, and attorneys have become less civil to one another.

The two concerns may feed off each other.

“Perhaps the conflicts in litigation have gotten uglier because continuing relationships among parties and lawyers have gotten weaker,” says Kenneth G. Dau-Schmidt, a professor at Indiana University School of Law who teaches labor and employment law.

“It may also be that lawyers have gotten less civil in litigation because of more intense competition for clients,” says Dau-Schmidt.

Amiram Elwork, who directs the law-psychology graduate program at Widener University, agrees: “People are so motivated to win at any price that they become very uncivil to each other—and play all kinds of games—which makes the litigation process much more costly.”

Not surprisingly, in-house lawyers are the most sensitive to rising litigation costs. But even among big-firm lawyers, more than three-quarters supported the idea that litigation costs have become prohibitive.

In-house counsel “say they’re tired of dealing with lawyers who are more concerned about billing hours than solving problems, who are taking the adversarial process to the extreme,” says Elwork, the author of Stress Management for Lawyers.

Clients, says Dau-Schmidt, could encourage civility - and probably decrease costs - by committing themselves to certain firms.

“So there’s no need for short-run chest beating,” he says, mentioning that clients could take the idea a step further by selecting lawyers who have good relationships with firms that often represent those who sue the clients’ businesses.

But lawyers may simply reflect a less civil society, says Ed Poll, a law firm consultant in Venice, Calif.

“The legal profession is not in isolation,” he says. “When was the last time you drove a car? We’ve got this thing called road rage now.”

“There are always lawyers who are jerks, and jerks tend to behave like jerks,” says John Heinz, who teaches law and sociology at Northwestern University. “I don’t mean to suggest that none of these concerns are real, but people have been complaining about it for some time.”

Career Satisfaction

Career satisfaction, it seems, comes with age. This is partially, career consultants say, because lawyers get more responsibilities as their careers advance; but it is also because those who don’t enjoy practicing law usually find something else to do after a few years.

Out of the lawyers with six to nine years of experience, only four in 10 reported career satisfaction. By comparison, six in 10 of those in practice a decade or more said they were satisfied with their careers—a 50 percent higher rate of satisfaction.

“Probably they’ve become partners or senior counsel, and by that time they’ve decided that the law is for them; they’re going to stay and they like it,” says Monica R. Parker, an Atlanta career consultant whose blog is called LeavingTheLaw.com.

Those who stay, she adds, likely have a good sense of what their work involves. Parker, formerly in private practice, says she sees a pattern among lawyers who experience career satisfaction. They usually have realistic expectations of what the work is and what employers expect from them. They also come into the practice with specific goals, Parker says, and select practices that appeal to them intellectually.

Indeed, out of the lawyers with at least 10 years in practice, 84 percent reported that they find the practice of law intellectually stimulating. “It can be trial and error,” Parker says. “There’s nothing wrong with that. Have the ideas about what you want, make mistakes and self-correct.”

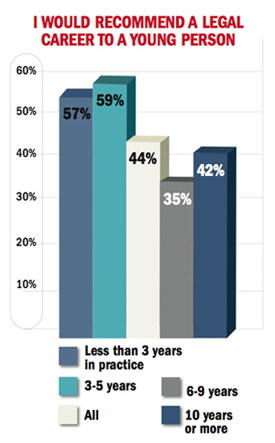

Recommending Law as a Profession

William R. Rakes, a litigator, knew by the age of 14 that he wanted to be a lawyer. His daughter Margaret, a children’s counselor, was leaning toward becoming a clinical psychologist. But he told her to think about studying law.

“I said if you go to law school, you can do lots of different things,” says Rakes, a partner with the Roanoke, Va., firm of Gentry Locke Rakes & Moore. His daughter, now a newly minted lawyer, isn’t convinced she made the right decision, but Rakes does not regret his advice.

Rakes, immediate-past chair of the ABA’s Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, wonders whether the low recommendation rate stems from those who fell into the profession by default—“who just end up in law school as an alternative, without really wanting to be a lawyer,” he says.

William D. Henderson, a professor at Indiana University School of Law, says that theory may be correct, but there is no way to know. Indeed, while only four in 10 said they would recommend a legal career to others, eight in 10 said they felt intellectually stimulated in their work and were proud to be attorneys.

Despite these high numbers, only 55 percent reported being satisfied with their career.

When Nell Jessup Newton entered law school, older lawyers told her that she shouldn’t because it was a terrible profession.

“I said: ‘Compared to what?’ I’d been supporting myself as a secretary,” says Newton, who today is chancellor and dean of the University of California’s Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco. She graduated from the school in 1976.

For many lawyers, Newton says, cynicism comes with experience. And when it comes to recommending law to young people, Pulse numbers reflect that notion. Only 42 percent of lawyers who’d been in practice 10 years or more stated that they would recommend a legal career to a young person. Comparatively, 57 percent of those in practice less than three years said they would make the recommendation.

According to Henderson, whose research focuses on education policy and the economics of the legal profession, some of the dissatisfaction may come from law schools not fully informing students about the profession’s demands.

The numbers back this assertion: Out of those surveyed, 54 percent agreed with the statement that law schools do a poor job of training young lawyers for the practice.

“So many people go to law school when the opportunity arises because [the career] pays a lot of money, it seems to be prestigious and it keeps options open for a long time,” Henderson says. “But the law is a jealous mistress. It’s one speed—fast—and it’s hard to be successful without being in with both feet.”

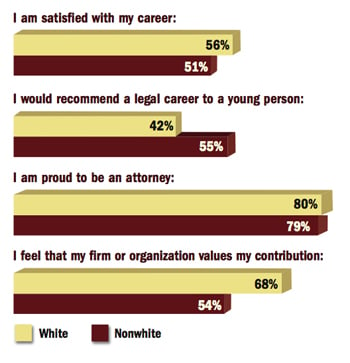

Lawyers who identified themselves as nonwhite were less satisfied with their careers than their white colleagues. Yet nonwhite lawyers were more likely to recommend the profession to younger people.

“On its face the numbers look contradictory, but I can see consistency,” says Jimmie Reyna, 2006-07 president of the Hispanic National Bar Association. Generally, says the Washington, D.C., attorney, lawyers of color see a lot of promise in the profession.

“Without a doubt they feel that they are not achieving their potential in the profession,” says Reyna, a partner at Williams Mullen, where he directs the firm’s international trade and customs practice. “But there’s a lot of room to grow.”

LuEllen Conti, career services director at Howard University School of Law, places law alongside medicine and education as a path to advancement. “I can’t speak for others, but certainly for black folks those have been the three main ways for upward mobility,” Conti says. “Even though there may be barriers and frustrations with the profession, [the law] is still viewed as one of the trifecta.”

When Phillip F. Shinn, 2006-07 president of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, meets other lawyers of color who have been in the profession 20 years or more, they often discuss the increase in minority attorneys.

“They’re very positive about that and want to encourage the generation behind them to go into the profession,” says Shinn, a litigation partner at San Francisco’s Thornton Taylor Becker & Shinn. Older lawyers, he adds, often witnessed how the law improved race-related issues firsthand. “I think there are some pioneers among our minority colleagues who had greater obstacles than we do,” Shinn says.

Satisfaction in Law and Life

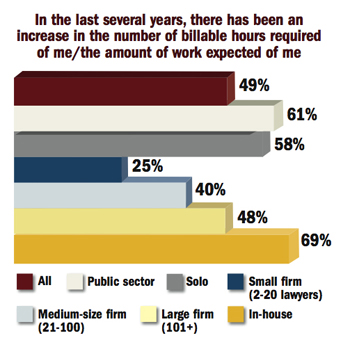

For many lawyers, career satisfaction is elusive. And far and away the least satisfied lawyers were from large firms (firms of 101 lawyers or more).

More often than not, lawyers in midsize or smaller firms said they were satisfied with their careers, as did 53 percent of sole practitioners. Freedom, say many solos, is the reason behind that result. If a sole practitioner charges $200 an hour, he or she only has to bill 25 hours a week to earn more than $117,000 a year.

“I bring home more than 50 percent of what I take in, so I don’t have to work as many hours,” says Ellen Rappaport Tanowitz, a sole practitioner in Newton, Mass., who writes about work-life balance issues. “You can have more free time and not be tied down to having to share profits with a partner.”

There are other considerations expressed by small-firm respondents. Only one in four reported workload increases, and three of every four said their firms valued their contributions. Not even half of big-firm lawyers (48 percent) said the same.

“I made the move because I found that I couldn’t control my destiny as well in a large law firm,” says Victor Medina, a name partner at the Pennington, N.J., firm Medina, Martinez & Castroll. Medina, who blogs about small-firm life, previously practiced corporate law at Bingham McCutchen and Drinker Biddle & Reath.

Work-life balance continues to be a problem for lawyers in private practice regardless of the size of their practice.

That said, no group of lawyers was more satisfied with their professional lives than those in the public sector, where overwhelming numbers said they were satisfied with their careers (68 percent), their work-life balance (62 percent) and the appreciation they feel in the workplace (70 percent).

Bench Strength

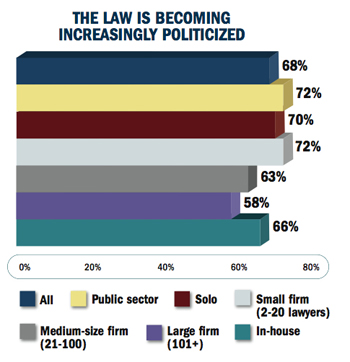

Two of every three lawyers surveyed said they are concerned that the court system they serve is becoming too political. The same number said they are concerned about the independence of the judiciary.

Lawyers from large firms and midsize firms expressed less concern about judicial politicization than others. But both groups expressed a slightly higher degree of alarm when asked about the issue of judicial independence.

Yet the highest degree of concern was registered among public sector lawyers, including local prosecutors, public defenders and lawyers for agencies at all levels of government. These are the lawyers who most often deal with hot-button social and political issues as a matter of everyday concern. And nearly three in four say they are concerned on both counts: That the law has become too political and that judges have lost a degree of independence.

Fueling such sentiments, say some government lawyers, might be the increasingly aggressive tactics of single-interest groups and blanket coverage by a sometimes less circumspect media. “What you’re seeing more often is the demonizing of public officials for the decisions they make, as opposed to a balanced, fair analysis,” says Charles W. Thompson Jr., executive director of the International Municipal Lawyers Association.

A former head of the Montgomery County, Md., law department, he mentions issues such as immigration, abortion and same-sex marriage. “If you’re not the lead person, you’re seeing it with respect to the person in the office who is being demonized—and also catching a feel of what the other person is going through,” Thompson says.

Darcee S. Siegel, chair of the ABA’s Government and Public Sector Lawyers Division, agrees with that theory. She also mentions that government lawyers tend to be in court more often than those in other practice groups, so they would see political interference firsthand.

“It’s increasingly becoming more of a problem,” says Siegel, the assistant city attorney for North Miami Beach, Fla., “and an issue that needs to be dealt with.”