ABA Medal recipient Dale Minami built a career around inclusion and civil rights for Asian Americans

Photo of Dale Minami courtesy of Minami Tamaki

Dale Minami didn’t know what the ABA was for the first nine years of his legal career. Then, in 1981, an invitation came.

The ABA was hosting a national institute of minority lawyers in Washington, D.C., along with several affinity bar associations. Minami was invited to help hash out reforms within the profession to help attorneys of color and their clients. But the subtext—based on Minami’s recollections and contemporary coverage from the ABA Journal—was an apology for past discrimination and an appeal to minority lawyers to join forces with the association.

The event prompted Minami and others to form the first national bar association for Asian Pacific Americans. Though that effort failed, he says, it planted the seed for the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, which was founded in 1988.

“And now we have an organization that was inspired by the ABA, truthfully, in many ways,” says Minami, who practices at Minami Tamaki in San Francisco and has been an ABA member for some 30 years. “They set us on the road to forming an organization. They welcomed us.”

On Aug. 10, Minami received the ABA Medal—the association’s highest honor—because he has spent his career working toward exactly that type of inclusion. It will not be the first ABA award for the attorney, who is also a past recipient of the ABA’s Thurgood Marshall Award and Spirit of Excellence Award.

Though Minami’s law firm calls him senior counsel in personal injury law, he’s better known as one of the lawyers who helped overturn the conviction of Fred Korematsu, the Japanese American man whose name is on a notorious and widely repudiated U.S. Supreme Court case. With far less publicity, he’s also helped blaze trails for Asian Pacific Americans and other people of color.

“He has a powerful passion for social justice that drives him,” says friend and former law partner Mike Lee, a solo in San Francisco. “And he puts his efforts and time into addressing his passion for justice.”

Early years

Minami finished law school at the University of California at Berkeley in 1971, making him just the right age to be influenced by the civil rights and anti-war movements. As Japanese Americans, his family was also interned during World War II, and that affected his thinking.

“My parents didn’t talk about the prisons,” he recalls. “And yet there was an undertone in our family that what was done to Japanese Americans was both racially motivated and unfair.”

That showed in small ways, he says. He recalls, as a child, his mother telling him that brutality against African American civil rights protesters simply wasn’t fair. As he grew up and began encountering racism personally, he started seeing parallels between that civil rights struggle and his own experiences.

That was the zeitgeist, says Minami’s longtime law partner, Don Tamaki.

“There’s a whole generation of people … who got politicized by watching the black civil rights movement,” says Tamaki, who graduated from Berkeley Law in 1976. “We thought about our situation and who we were, and we woke up.”

Minami started applying those lessons right out of law school by co-founding the Asian Law Caucus, a community interest firm dedicated to the rights of low-income Asian Americans. There was nothing like it at the time, but the need was there. An early case challenged the San Francisco Police Department’s practice of fighting Chinatown gangs by arresting young Asian men for standing on street corners.

There was no funding. Tamaki says the Asian Law Caucus was originally run out of a Volkswagen van, where Minami would keep a suit to change into before court. But the enterprise attracted law students like Tamaki, who went to Berkeley Law to do civil rights work. He says Minami was a leader in that crowd, in part because he was one of the few Asian American attorneys doing visible civil rights work.

He was also one of the few Asian American attorneys at all in those days, friends say. And he didn’t fit the stereotype of a quiet, compliant Asian American, says friend and colleague Joan Haratani.

“He was bold, articulate, outspoken, courageous,” says Haratani, a partner at Morgan, Lewis & Bockius in San Francisco. “The guy who gave us permission to be young, successful Asian American lawyers was Dale Minami.”

The Asian Law Caucus lives on as a part of the civil rights group Asian Americans Advancing Justice. But after a few years, Minami felt it was time to hand it over to younger lawyers, so he and some friends started their own firm. Though it was a struggle at first to convince clients that they didn’t work for free, the firm now known as Minami Tamaki has endured for more than 40 years, balancing fee-bearing work with cases focused on civil rights, especially for Asian Americans.

Vindication

By far the most famous of those was the relitigation of the case against Korematsu, who as a young man defied the federal government’s orders to report to an internment camp. The Supreme Court, notoriously, upheld the internment as justified by national security concerns.

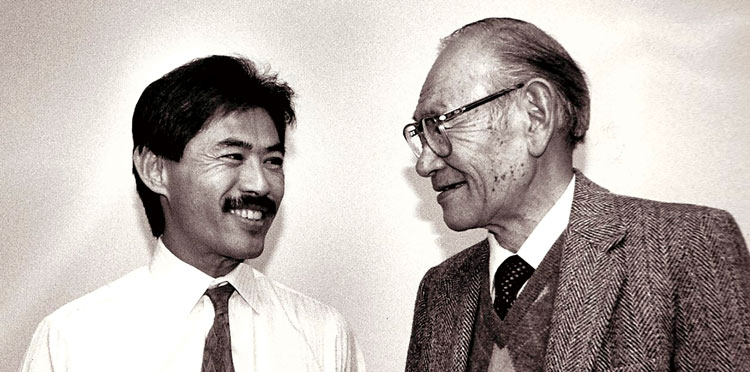

Dale Minami (left) was one of the lawyers who helped overturn the conviction of Fred Korematsu, the Japanese American whose case challenging World War II internment was heard by the Supreme Court. Photo courtesy of Minami Tamaki

Almost 40 years later, law and history professor Peter Irons unearthed documents showing that federal agencies had actually concluded that most Japanese Americans were loyal citizens. However, the paper trail said, the Justice Department deliberately suppressed that evidence in Korematsu’s case, as well as in earlier cases against Minoru Yasui and Gordon Hirabayashi. The situation called for a lawyer.

Minami says he got the job because he was one of the few Japanese Americans doing impact litigation on the West Coast. But of course it was also personal for him and for many on the litigation team he assembled.

“Most of the lawyers in the group were Japanese Americans, and they had parents who were incarcerated, including my own,” he says. This gave the group a mission “to vindicate not just our parents but the entire Japanese community.”

That passion and pressure carried the team through a year of secret work on the case. Both the age of the case and the wealth of documentation posed challenges. In the end, a Northern California district court granted a writ clearing Korematsu, and the other two men won partial victories from district courts in Oregon and western Washington. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco ultimately cleared Hirabayashi, but Yasui’s appeal was mooted by his 1986 death.

The relitigated Korematsu v. United States was a victory for the Japanese American community, although the precedent was never formally overturned. In 2018’s Trump v. Hawaii, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. said the Korematsu decision was “gravely wrong” and “has been overruled in the court of history”—but Minami says he feels that this is not sufficient, especially because it came from a majority opinion that gave great deference to executive power.

Creating community

But the courtroom isn’t the only place to support the community. Minami has also been a leader in legal circles, starting with helping to form the Asian American Bar Association of the Greater Bay Area. He’s also been involved at the beginnings of many state and national bars for Asian Americans, and Haratani says he’s mentored numerous younger attorneys like her.

Inspired in part by racism he experienced as a young lawyer, Minami has worked for years on diversifying the bench. He has served on the judicial screening committee for former California Sen. Barbara Boxer, as well as the California State Bar’s Commission on Judicial Nominees Evaluation.

“It starts to change the whole culture of the bench,” Minami says.

Because of that, friends say aspiring judges seek Minami’s advice.

“If you talk to any Asian American judge in the state of California, I bet you nine out of 10 would know Dale, would have spoken to Dale, would have gotten some advice from Dale,” says Judge Edward Chen of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, who worked with Minami on Korematsu.

Friends say Minami does that work in part through charisma.

“He can certainly persuade people, he can inspire people,” says Tamaki. “And he’s very clear about his sense of right and wrong.”

That sense continues to guide Minami today. In response to current events, he’s helped start a campaign called Stop Repeating History, which draws parallels with the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Japanese internment and the “travel ban” at issue in Trump v. Hawaii.

“I believe that the rhetoric of this country is just wonderful, but the actions of the country speak otherwise,” he says. “Part of my mission, and part of my passion, is to have that rhetoric match up to its actions as much as we can.”

Members Who Inspire is an ABA Journal series profiling exceptional ABA members. If you know members who do unique and important work, you can nominate them for this series by emailing [email protected].

This article first appeared in the September-October 2019 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline “Righting Injustices: ABA Medal recipient Dale Minami has built a career around inclusion and civil rights for Asian Americans.”