Chief Justice Roberts slides into the high court’s ideological middle with the retirement of Justice Kennedy

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/Courtesy of Executive Office of the President of the United States/Franz Jantzen; Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States/Wikimedia Commons.

Just two days after Justice Anthony M. Kennedy announced his retirement June 27, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. made his way, as he has done for many years, to the Judicial Conference of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Richmond, Virginia, for which Roberts is circuit justice.

“There’s been some news lately,” Circuit Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III told Roberts in an understated reference to Kennedy’s retirement announcement.

The chief justice smiled and then lauded Kennedy as “an extraordinary man” and “extraordinary jurist” who was “deeply committed to collegiality and civil discourse.” The amiable conversation between Wilkinson and Roberts continued for about 40 minutes, with Wilkinson asking about an academic study of interruptions on the bench, about which books the chief justice planned to read over the summer, and about how well the justices get along with each other.

“Relations among the justices are very collegial,” Roberts said. “We have sharp disagreements on matters that are quite important. … However direct the disagreements may seem, we do know that we are all in it together.”

One matter Wilkinson didn’t ask about, and Roberts did not bring up, was the new role the chief justice will assume when the court returns for a new term Oct. 1—median justice. That’s the court member at its ideological center, as measured by political scientists who study the court.

“Roberts is going to be in a position of great power on the court,” says Lee Epstein, a professor at the Washington University School of Law in St. Louis who specializes in law and political science.

Kennedy has been the median justice since Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s 2006 retirement. And when they served together, they often traded spots at the court’s center.

Although Kennedy did not like the term swing justice, he could not escape being referred to by that appellation by many court observers, based on his position as the justice who often joined the court’s four conservatives but sometimes cast his vote with the liberal bloc on issues such as LGBTQ rights, abortion rights and affirmative action.

Roberts was in the minority in recent decisions in those areas but has been successful in pushing the court to the right on narrowing the scope of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, sharply limiting when K-12 schools may consider race in assigning students to a particular school, and in considering many criminal matters.

“Roberts is not Kennedy,” Epstein says.

Moving to the Right

Epstein was the co-author of a seminal 2005 article in the North Carolina Law Review, “The Median Justice on the United States Supreme Court.” The median justice “is essential to secure a majority” on the court, Epstein and her co-authors, Andrew D. Martin and Kevin M. Quinn, wrote. The article introduced the “Martin-Quinn score,” a method of classifying each justice on an ideological scale that doesn’t rely exclusively on past votes.

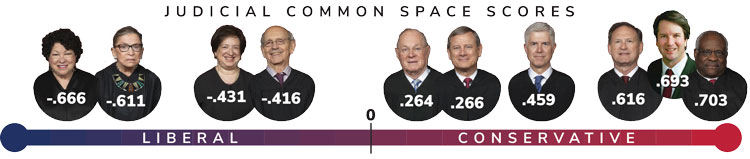

Epstein and Martin joined two other scholars in a 2007 article, “The Judicial Common Space,” discussing another way for classifying judges based on the party of their political patrons. These scores place current court members from left (most liberal) to right (most conservative) in this order: Sonia Sotomayor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Stephen G. Breyer, Roberts, Neil M. Gorsuch, Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Clarence Thomas.

If Brett M. Kavanaugh, President Donald J. Trump’s nominee to succeed Kennedy, is confirmed by the U.S. Senate, he would fall to the right of Alito but just to the left of Thomas on the ideological scale. (All but one of those on Trump’s long list of potential nominees would have aligned to the right of Roberts. Only U.S. Circuit Judge Thomas M. Hardiman, considered a finalist for the past two vacancies, would fall to the left of Roberts.)

Epstein says Kennedy has been the median justice continuously since Roberts became chief justice in 2005.

“There is no other justice who has dominated an entire court era,” she says. “Kennedy dominated the entire Roberts era.”

Of course, the Roberts era continues—now with him at the center.

Epstein says the last time a chief justice was the ideological median on the court was in the 1937 term, with Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes in that position. But it was only for about half the term, when Justice George Sutherland retired and Justice Louis D. Brandeis became the median.

“We really don’t have a good modern-day example of the chief justice being the center of the court,” Epstein says, noting that Chief Justices Warren E. Burger and William H. Rehnquist were well to the right of center.

Roberts leans right on many issues, although his crucial vote with the court’s liberal bloc in 2012 to uphold the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act, in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, has long stuck in the craw of American conservatives.

This article was published in the September 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title "Center Court: The chief justice slides into the high court's ideological middle with the retirement of Justice Kennedy."