Sept. 3, 1838: Frederick Douglass escapes to freedom

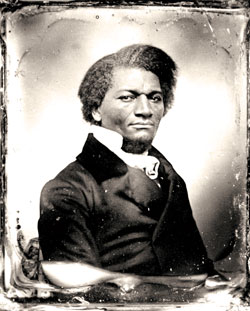

Photo of Frederick Douglass by AP Photo/File

As a train pulled out of Baltimore, a light-skinned black man jumped aboard a rail car designated for African-Americans. Dressed in a red shirt and a dark tarpaulin hat with a loose black scarf around his neck, he bore the swagger of a sailor. His name was Frederick Bailey, but his papers wouldn’t reflect that. They belonged to a real sailor—a free black sailor. He had boarded the train at the last second, and without a ticket, to avoid the close scrutiny he would have received at the ticket desk. Maryland was a slave state, and he preferred a distracted conductor to a ticket clerk who might focus on the discrepancies in his paperwork. Long before he became Frederick Douglass, Frederick Bailey was a slave.

He had attempted escape before. Because of his intelligence, Bailey was deemed both valuable and dangerous. Though it was illegal for him to do so, he’d learned to read and write. In 1836, he’d planned an escape with four others using letters he had forged. When the plot was compromised, Bailey ended up in the Baltimore shipyards as a caulker, hired out by his master on a contract basis. And while working at the shipyards, he learned the language and manner of the sailors around him.

The conductor worked his way around the car, asking the black travelers for their “free papers.” When he came to Bailey, the passenger calmly explained he did not carry them while at sea. “But you have something to show that you are a free man, have you not?” said the conductor. “Yes, sir,” Bailey answered. “I have a paper with the American eagle on it, and that will carry me around the world.” The conductor glanced at the papers and moved on.

The train took Bailey to Havre de Grace, where he caught a ferry across the Susquehanna River, and then a train to Wilmington, Delaware, another slave state. A steamboat took him to Philadelphia, where he caught another train to New York City—and a free life.

“No man now had a right to call me his slave or assert mastery over me,” Douglass wrote years later. “I was in the rough and tumble of an outdoor world, to take my chance with the rest of its busy number.”

This article originally appeared in the September 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “An Escape to Freedom.”