Should this toy be saved?

Illustration by Bob Schuchman

After a 6-year-old Canadian girl swallowed 19 superstrong, pea-size magnets in March, she told her mother she thought they were candy. The magnets failed to pass through naturally, and a surgeon removed them three days later, finding a perforated small intestine, ulcerations in the stomach and two small holes in the bowel.

The rare-earth magnets with the brand name Buckyballs had been a gift for the woman’s two children, the other a 2-year-old. “I thought nothing of it,” she told a reporter.

The girl’s mother likely had no way of knowing of the problems rare-earth magnets can create, unless she happened upon news accounts of similar incidents or the magnets came packaged with a warning label that she actually read. Or perhaps she just wasn’t careful enough with her children handling small objects.

The latter view tends to dominate in comment sections in blogs about Buckyballs. Their misuse attracts zingers aimed at the parents by invoking, among other things, Darwinism and questionable fitness for raising kids. But the issues for product safety are more subtle and complex.

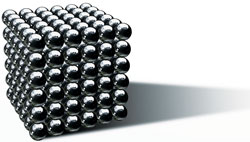

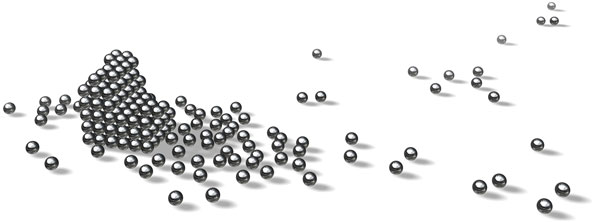

Last July, the Consumer Product Safety Commission filed an administrative complaint seeking to ban the sale of Buckyballs, which were marketed as adult novelties—a sort of work-desk alternative to doodling. They can be stacked, aligned and extended to build forms and shapes that seem to defy gravity. But they sometimes find their way down the gullets of children and then, with strength exponentially greater than typical magnets, they try to join each other.

The company folded several months later, giving up its catchy PR effort (“Save Our Balls” got a lot of sympathetic news coverage) and walking away from an expensive court battle against the agency. The CPSC later sued two more companies, Zen Magnets and Star Networks, which have continued selling the strong-magnet balls. The three cases might be combined.

The products are still being marketed, and tens of millions of Buckyballs remain in consumers’ hands, as well as loose on floors under furniture. The issue brings bright light and sharp focus on an agency that until just a few years ago had receded into the fuzzy, forgotten margins of the federal bureaucracy.

In recent years, the CPSC has enjoyed a resurgence thanks to an unusually strong congressional response to public fears after the “year of the recall” in 2007. Millions of toys, mostly imports from China with well-known names such as Thomas the Tank Engine, were pulled from store shelves because of paint that contained extremely high amounts of lead. The scare came just months after melamine-tainted pet food from China killed and sickened American cats and dogs; and then toothpaste from China was found to contain a poison used in antifreeze.

Corrective legislation in the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008 brought the most sweeping change in product safety law since the agency’s formation. Among other things, it called for third-party testing of durable products for infants, a significant increase in fines against violators and whistleblower protections.

The legislation also included significant increases for staff and funding of the CPSC. The agency had a high of 978 employees in 1980, just before the Reagan administration’s deregulation efforts began, with the CPSC as a prime target; after the Bush administration took further aim at the agency in the early 2000s, the staff had dwindled to 385 by FY 2008. President Bush also made a series of controversial nominations for the commission, criticized as deregulators. Two of them failed—one withdrew, the other was not confirmed as chair.

“It was just a neglected agency,” says Consumer Product Safety Commission Chairwoman Inez Tenenbaum, who was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2009. “I don’t know if it was by design to try to cripple this agency, but it certainly needed a lot of attention and resources.”

And some believe that, by design or not, some companies in regulated industries found less need to pay attention to the CPSC.

“Industry had grown lax during a period leading up to the 2007 recalls,” says Ann Brown, who chaired the CPSC from 1994 to 2001. “They thought ‘we have a more sympathetic group in there, so we don’t have to be so tough on ourselves.’ ”

Brown had inherited an agency eviscerated by the deregulatory policies of the 1980s, but was considered very effective for using what clout she had—publicity, especially by calling out problems with certain products during regular appearances on NBC’s The Today Show.

“Industry critics said that when I opened the refrigerator door and the light came on, I offered up a sound bite,” quips Brown, who had been vice president of the Consumer Federation of America for 15 years before going to the CPSC. “They were right.”

Illustration by Bob Schuchman

ACTIVIST ORIGINS

The consumer movement largely developed by Ralph Nader in the mid-1960s reached a pinnacle with the creation of the CPSC in 1972. It had been recommended by the National Commission on Product Safety, which Congress created in 1967 to look at the effectiveness of the thin patchwork of consumer safety oversight spread around government. The commission determined that industry self-regulation, existing statutes and product liability litigation did not adequately protect the public.

Thus the Consumer Product Safety Act of 1972 directed the new agency to “protect the public against unreasonable risks of injury.”

Launched with fanfare and the broad mission of policing approximately 15,000 varied products, the CPSC had expectations so great that, in hindsight, some amount of failure was guaranteed. Even more was visited upon it.

The business community had been somewhat bemused by the fast-growing consumer movement and was seen as slow to respond. But it quickly made up for its tardiness.

Some observers point to the so-called Lewis Powell memo as a galvanizing force in building opposition to a consumerism juggernaut, one among several trends Powell saw as threats to business and conservative values. Just months before his nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971, Powell, a conservative Democrat and former ABA president, wrote a detailed blueprint for corporations to respond to Nader’s consumer movement specifically and for conservatives to counter growing liberal initiatives generally.

The Powell memo, which went viral once Internet use became commonplace, was addressed to his client, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Noting “the stampedes by politicians to support almost any legislation related to ‘consumerism,’ ” Powell wrote that “there should be no hesitation to attack the Naders … and others who openly seek destruction of the system.”

There was a sudden swell of business and conservative opposition. The National Association of Manufacturers, which has had a major interest in product safety regulation, moved its headquarters to Washington, D.C., in the early ’70s; the Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs of major corporations, was created in 1972; the American Legislative Exchange Council came into being the following year. A slew of conservative think tanks and other initiatives soon sprang up.

Atmospherics and optics in Washington soon began to change through a mix of the conservative backlash and some missteps by the agency—the latter being both real and perceived in a town where perception is almost everything—in some of the first handful of mandatory standards it developed through rule-making.

The quick change became obvious to David Pittle, one of the original five CPSC commissioners in 1973, when he was nominated for a second term in 1977 and faced a confirmation hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.

This time around, the message from committee members was different. Previously, Pittle had been lectured about the importance of protecting consumers and notifying the public of dangerous products.

“Now they were saying, ‘You can’t overregulate; you’ve got to be careful,’ ” Pittle recalls. “There were concerns about companies surviving. The tone was different.”

Photo of Robert Adler by David Hills.

Then Ronald Reagan became president in 1981 with a mission to shrink government and lighten the regulatory load on business. Reagan’s director of the Office of Management and Budget, David Stockman, almost immediately sought to abolish the CPSC. That attempt was blocked in Congress but required compromise: significant amendments to the CPSA, emphasizing voluntary industry standards over mandatory ones. That shift encumbered the rule-making process (the creation of mandatory product standards) by requiring, among other things, cost-benefit analysis of even rejected alternatives, according to critics such as Pittle and Robert Adler, now a commissioner but formerly a high-level CPSC staffer in the 1970s and ’80s.

Until the 1981 pushback, the agency had been averaging approximately one mandatory standard each year. In the 32 years since, according to Adler, the commission has averaged only one standard every 3½ years. While Stockman didn’t kill the agency, he bled it white.

“I got a directive from OMB and David Stockman telling me to RIF 300 people and that the budget would go down about 30 percent,” says Pittle, the agency’s acting chair in 1981. “After failing to abolish it, they were trying to cripple it.”

Other agencies involved in safety regulation, such as those for national highway transportation and environmental protection, were hit too. “But nobody else got the big-size cuts we did,” Pittle notes. “And they layered on the due process requirements to slow us down.”

Nancy Nord, now on the commission, remembers it differently. She was a minority staff lawyer at the time for the House Commerce Committee, which played a major role in the 1981 amendments. “The ’81 amendments were focused at fine-tuning the statute and making it work better,” says Nord, who helped write them.

Photo of Nancy Nord by David Hills.

Nord has, though, been critical of the sweeping 2008 legislation that returned bodies, dollars and authority to the withered agency. “They were passed very quickly,” she says of revisions and expansions made in the wake of millions of toys being recalled and the broader scare over Chinese imports. “So perhaps not as much time and thought were given to them as one would like to see when doing major legislation.”

For example, Congress lowered the standards for lead content in products and, in an unusual move, made it retroactive. The change was done over a few years, with the parts-per-million requirements gradually tightening. Some industries that thought they could weather it were crushed by the economy’s extreme downturn—products, such as shirts with lead in the buttons, remained on the shelves when the PPM eventually ratcheted down and could no longer be sold.

Responding to criticism, Congress tweaked the law in 2011 with carve-outs to help some products, such as bicycles with lead alloy in their spokes; the American Library Association also successfully lobbied to keep pre-1976 children’s books on the shelves despite traces of lead in printer’s ink from those days. Consumer advocates concede that some small damage was done by the 2008 law and needed undoing.

But the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act, even with tweaks, was seen as a mandate for the agency to be more aggressive. Congress streamlined the agency’s rule-making process for toys and products for infants and toddlers. The snail’s pace for developing mandatory standards since 1981 suddenly sped up. “In the five years since the CPSIA was enacted, we’ve put out 40 [infant-product] final rules,” says CPSC chairwoman Tenenbaum. “That’s unprecedented, a big change.”

AN ‘AGGRESSIVE SWING’

It was a newly re-energized and more muscular Consumer Product Safety Commission that ramped up the Buckyballs issue with litigation. The agency had gone 11 years without filing a lawsuit demanding recall. In December it filed suit concerning another product, the Nap Nanny, a portable infant recliner marketed by the company Baby Matters. Babies had been able to get out of restraints and into compromising positions—there were five deaths.

As with Buckyballs, the agency first worked with the company in coming up with label warnings. But eventually the CPSC decided, again, that warnings were not sufficient and demanded the recliner’s removal from the market. As the agency was reeled in over the years, most extensively during the Reagan and more recent Bush administrations, product warnings and voluntary standards took hold as major tools for industry and the agency.

“For whatever reason, they’re now on a very aggressive swing,” says Lee Bishop, counsel in the D.C. office of Miles & Stockbridge and a former senior counsel for product safety and regulatory compliance for consumer products at General Electric. “We’ll see if this is a significant change in policy.”

According to the administrative complaint concerning Buckyballs, “Warnings are ineffective because parents and caregivers do not appreciate the hazard.”

A corollary to that—and an answer to those who point fingers at the parents—might be found in a scholarly article commissioner Adler published in 1995: “Blameless children pay the price for their caregivers’ ‘sins.’ ”

After determining that warnings failed as a safety measure for Buckyballs, the commission could have initiated rule-making proceedings, which would apply industrywide for various companies selling the magnets. But some inside the agency said that would take too long for addressing an urgent problem. It could have gone to federal court to prove the product is an “imminent hazard,” but the agency likely balked, in part, because—unlike the Environmental Protection Agency, for example—it has little experience in that venue.

In fact, the CPSC got spanked in federal court in Maryland last October in another matter, when a judge issued a stinging opinion saying it had violated its own originating statute in operating a new database for online posting of complaints about the safety of particular products. The database was mandated by the 2008 legislation, but it is up to the agency to design the bells and whistles.

Republican appointees wanted to limit posting privileges to consumers and public safety officials—keeping out, for example, plaintiffs lawyers and consumer activists; Democratic appointees, holding sway, made the site wide open.

In perhaps one of the most heavily redacted court opinions in history—no mention of the company, the product, the consumer or the harm—U.S. District Judge Alexander Williams Jr. found that the CPSC failed to ensure that information on the database meets the statutory requirement that it be “materially accurate.”

The agency abused its discretion in publishing a report based on “coincidence” when “the evidence strongly suggests that [redacted] stemmed from other sources,” the judge wrote, adding that the odds of Company Doe’s product being related to the problem are “significantly lower than a coin flip.”

The commission appealed to the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Richmond, Va., but withdrew in December, without comment, just before briefs were due.

Photo of Erika Jones by David Hills.

Taking the administrative law path to sue Buckyballs, the CPSC alleged that the toy constitutes a “substantial product hazard” and should be taken off the market. Then the commission threw a curveball that raised eyebrows even among lawyers specializing in the difference between corporate and individual liability for defective products.

After the limited-liability corporation filed for dissolution in Delaware last December, the CPSC asked to amend its administrative complaint in order to name Craig Zucker, co-founder of Maxfield & Oberton Holdings, which developed Buckyballs, as an individual and as a “responsible corporate officer.”

The lawsuit was brought to determine whether Buckyballs present a “substantial product hazard” that should be removed from the market. But the CPSC then came back to make sure the company’s co-founder is on the hook for any expenses for recalls or refunds.

Zucker had bumptiously fought the agency in the court of public opinion, from TV to the blogosphere. And he challenged it vigorously toward the end as the agency tightened the screws over nearly two years, which had included agreements over labeling, withdrawing product from stores that have significant children’s sections, and agency-company joint informational video campaigns.

“Some might view the agency’s move against him as reprisal,” says Michael Gidding, a Bethesda, Md., lawyer who was at the CPSC at its inception and spent 30 years there, including as counsel in both the compliance office and with the general counsel. He now represents companies entangled in product safety issues.

“What is at issue here is not an attempt to make Mr. Zucker liable for any violation, but rather to impose the burden of conducting a recall upon him,” wrote Erika Jones, a lawyer representing Zucker as a nonparty participant in the lawsuit against his former company. Jones, a partner in the D.C. office of Mayer Brown and a former chief counsel for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, argues that the agency’s bid to amend the complaint wrongly applies two Supreme Court decisions—known as the Dotterweich (1943) and Park (1975) cases—to tag Zucker as a “responsible corporate officer.”

Those cases, typically used in FDA actions involving social welfare issues, concerned an official for a company alleged to have adulterated and repackaged drugs for sale; and the CEO of a grocery store chain with rats infesting its warehouses. More recently, the Supreme Court’s 2003 decision in Meyer v. Holley said there must be clear congressional intent for a statute to impose a duty on “responsible corporate agents,” which Jones says is not in the pertinent section of the CPSA.

That novel try aside, the Buckyballs case highlights the intersection of two seemingly similar but strikingly different areas of the law: product liability and product safety. In tort cases, contributory negligence often can limit or prevent recovery of damages; but Congress crafted the Consumer Product Safety Act in a way that isn’t concerned with fault, so when consumer misuse leads to injury and death the question becomes one of how easily the problem can be fixed—from warning labels to informational campaigns to repairs to product-ending recalls.

Buckyballs rolled through the intersection of those two policies, prompting the question: How far should the government go in protecting us, sometimes even from ourselves? The answer often is in the philosophical-cum-ideological eye of the beholder.

RISK CALCULUS

Created as an independent agency, the CPSC is structurally bipartisan: Four of its five commissioners are balanced by political party appointment, but the fifth commissioner belongs to the political party holding the executive branch. This provides a political majority, should that matter in a science-based agency. The political makeup intended some accountability and has put the key term in the originating statute’s charge, protecting the public from “unreasonable risk,” through a lot of stretching and crunching over the years.

The Buckyballs flap continues the tradition.

The CPSC staff, extrapolating from data obtained from 100 hospitals under contract around the country, estimates that there were 1,700 emergency room visits for ingestion of high-powered magnets between 2009 and 2011, and reports continue to come in. The products are still being sold by several other companies as well.

But, again, tens of millions of the balls went into the marketplace. The lawsuit lists several instances in which Buckyballs were ingested, including one involving a 9-year-old who used them to mimic tongue and lip piercings; the agency can produce others in administrative hearings. The agency says that since 2009 it has learned of more than two dozen “ingestion incidents, with at least one dozen involving Buckyballs. Surgery was required in many incidents.”

“The denominator matters,” says Gidding, the former CPSC compliance lawyer.

“If you have a product involved in incidents with one out of every 100 products, yeah, look at it, but if 5 million are sold over 10 or 12 years and you have five incidents, what does that tell you of foreseeability? Those become philosophical questions.”

The answer, as far as Buckyballs are concerned: “Some may say, ‘Why would the government bother with something labeled for adults,’ but many consumers aren’t aware that the CPSC also looks at foreseeable misuse and abuse. We found that after a recall announcement—for stronger labeling—and an education campaign, working jointly with the company for nearly two years, it did not slow down the number of incidents of ingestion, and the severity of those leading to surgery was increasing,” says CPSC spokesman Scott Wolfson.

Wolfson speaks for the CPSC chairwoman, Tenenbaum, who—along with fellow Democratic appointee Adler on the commission—voted to sue.

But, again, commissioner Nord sees it differently. She joined the CPSC as a Republican appointee in 2005 and was acting chair from July 2006 through May ’09. Nord voted against suing, but says she is open to possible rule-making concerning the magnets in general.

(In December Nord voted in favor of suing over the Nap Nanny, but issued a statement saying she did so because the legal theory concerning the “reasonably foreseeable misuse” of a product “deserves a thorough vetting by an administrative law judge. This concept remains nebulous and incompletely defined even as the agency has dealt with it over the years.”)

But with the Buckyballs suit, she tells the ABA Journal, “I can’t remember when this agency has sought to ban a product being safely used by the group it’s intended for because it is being unsafely misused by a group of users it was never intended for. I think that’s a pretty startling concept.”

In the not so distant future, there likely will be an entirely new agency, as far as the cadre of commissioners is concerned. President Obama has the opportunity to create and keep a Democratic majority on the commission that would run beyond his second term.

One question will be whether the number stays at five. During the Reagan administration, Congress began appropriating only enough money to fund the offices of three commissioners. It remained that way until 2008, when Congress pulled the agency up from the depths.

Commissioners are appointed to seven-year terms from the end date of their predecessor’s appointment and can get one-year extensions. No more than three can be of the same political party.

COMMISSION (IN)FLUX

The current commissioners either have terms expiring or are serving extensions of earlier ones.

Confirmations typically are done in bipartisan pairs. For example, in January Obama nominated Detroit trial lawyer Marietta Robinson, but she won’t go on until he nominates a Republican for the other vacancy. Then soon there would be a need for paired nominations to replace Nord and Tenenbaum.

The agency, which is best known for keeping its eye out for hazardous children’s products, has been accused of overreaching and underregulation by opposing forces over the years. Again, that often comes down to the beholder’s philosophy. As for the CPSC’s recent aggressiveness, how that plays out surely depends on the expected influx of new commissioners.

• For further developments, read “Dangerous desk toy Buckyballs voluntarily recalled by retailers”