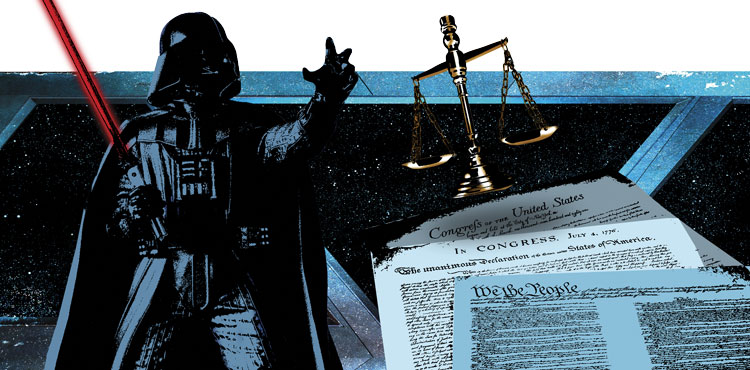

How serendipity, 'Star Wars,' Sunstein and constitutional law intersect

Illustration by Brenan Sharp

U.S. Supreme Court justices tend to be storytellers, weaving complex and persuasive narratives about the meaning of the Constitution. So while working on this article, I considered the creative, inspired and spontaneous discoveries that all writers—including Supreme Court justices—inevitably make and then draw upon.

I took breaks from my writing to watch Neil M. Gorsuch’s confirmation hearings on television. Gorsuch was playing his hand carefully and close to the vest, refusing to give away any clues about how he would rule in pending or possible future cases. He also discounted his own feelings and hedged around personal beliefs regarding matters that might come up before the court. When provoked, he repeated the pragmatist’s mantra that the role of judges is simply to “follow the law and decide cases.”

Gorsuch embraced the label of being an “originalist.” He conveyed a softer version of originalism than his more severe textualist predecessor, Justice Antonin Scalia, had. Gorsuch observed that discovery of the original meaning of the law as enacted—and of the Constitution—is not an “ideological thing,” and that all judges and justices are originalists and literalists of a sort, employing and deferring to original textual meanings, whether of a statute or of the Constitution itself.

The hearings seemed haunted by the ghost of Judge Merrick Garland. But Gorsuch, handsome and personable, did not come across as an ideological extremist. He claimed to be a judge who voted consistently with the majority and had only been reversed one time, “maybe.”

I turned off the TV. Clearly, there was something missing from Gorsuch’s testimony. And some of it had to do with the topic of this Journal article: how Supreme Court justices do not simply uncover the original meaning of constitutional texts. Nor are they merely technicians or craftsmen applying law to the facts. Justice requires great artistry. And there are profound and unacknowledged forces that shape judicial stories, fitting law with desired—but seldom predestined—outcomes. Indeed, the entire narrative arc of our constitutional law saga is full of surprise, mystery and plot reversals worthy of a great novelist.

Gorsuch’s evocations of simple judicial mantras as shorthand for the work of appellate judges was an obvious cover story. He failed to acknowledge the creative, inspired and spontaneous discoveries that all storytellers, especially Supreme Court justices telling stories about the meanings of our Constitution, inevitably make and then draw upon.

Narrative Jurisprudence

Legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin famously compares the evolution of constitutional law with the writing of a chain novel in which a group of writers creates new chapters built upon the choices made in previous chapters by other authors. Dworkin emphasizes the constraints and demands that earlier chapters impose upon subsequent authors. Think here, obviously, of the limitations of precedent and stare decisis.

My version of Dworkin’s analogy these days is with the development of the complex master plots of multiseason, serial TV programs such as The Sopranos and The Wire or, more recently, Breaking Bad, House of Cards or Homeland. In these shows, the narrative arcs of meta-stories are reinvented over multiple seasons by collaborative and ever-shifting casts of writers, directors and actors. Creative possibilities are compounded exponentially by the consciousness of multiple authors working together across time.

Likewise, the narrative arcs of episodic multiseasonal constitutional law sagas are collectively reshaped in ways never originally intended or anticipated. Unfolding storylines must fit or cohere with what has come before.

Of course, this is certainly not how Supreme Court justices typically understand their own work. But then, honestly, the justices are not paid to be completely candid or self-effacing about their internal creative processes, especially in their public pronouncements.

creative transformation

Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein has adopted the term serendipity in attempting to explain the creative forces—both demands and constraints—at work in literature and in law. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines serendipity as: “the faculty or phenomenon of finding valuable or agreeable things not sought for.”

Sunstein puts it this way: There is an “immense role of serendipity and happenstance in the creative imagination. ... Serendipity imposes serious demands on the search for coherence in both literature and law (and history and life as well).”

In an essay reprinted in the Washington Post, “How Star Wars Explains Constitutional Law,” Sunstein reviews Chris Taylor’s book, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe: The Past, Present, and Future of a Multibillion Dollar Franchise. The book provides a point of departure for Sunstein’s playful meditation on “the force” of serendipity in constitutional law, and it illustrates how storytellers—both moviemakers and Supreme Court justices—often conceal or refuse to acknowledge authorial responsibility for serendipitous creative decisions, with claims that their discoveries were externally predetermined.

For example, akin to Gorsuch’s testimony, Star Wars creator George Lucas makes the originalist claim that the master plot of the narrative arc of the Star Wars saga was predetermined and codified in a book Lucas identifies as The Journal of Whills. But Taylor’s behind-the-scenes reconstruction of the writing of the Star Wars screenplays exposes Lucas’ claim as “wildly inaccurate,” a pretextual cover story, akin to the stories the justices tell to the public and, more important, retrospectively tell to themselves.

Lucas did not originally anticipate that Darth Vader would be Luke Skywalker’s father. (It is an “originalist myth,” Sunstein wrote, that the character’s name is a play on “dark father.”)

Writing the final scene of The Empire Strikes Back, Lucas had Vader say to Luke (aka Lucas?): “Join me, and we can rule the galaxy as father and son.” These words produced an aha moment of creative discovery for Lucas, revealing unexplored narrative possibilities and suggesting new directions in future, yet unwritten episodes of the saga.

What does this have to do with constitutional law? Sunstein argues that similar creative transformations occur in legal storytelling, especially when justices determine constitutional meanings. For example, what was once merely a shard of interpretive dicta in an earlier Supreme Court decision may morph into the holding of another case years later, suggesting a story arc about the meaning of the Constitution serendipitously rediscovered in the reverberations of a different time.

Sunstein’s takeaway “I am your father” moments are just as pivotal in the epic sagas of constitutional law as in Star Wars and allow constitutional texts to cohere with new meanings over time. He identifies Brown v. Board of Education as one iconic “I am your father” decision. In my capital punishment class, we read Furman v. Georgia’s revelatory holding that the Eighth Amendment now proscribes the death penalty as cruel and unusual punishment as another. A mere four years later there is an abrupt “I am not your father after all” reversal in Gregg v. Georgia, after the composition of justices on the court and popular political sentiments had shifted. Sunstein also observes that for many years federal and state governments punished speech determined to be dangerous.

According to Sunstein, the robust protection now afforded to political speech protected as free speech (under the “clear and present danger” test) came about in the “I am your father” decisions of New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) and Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), revisiting the meaning of the First Amendment and rethinking the law that had come before it.

There is also the influence of a contextual history that often bleeds into Supreme Court decisions alongside any originalist designs, as well as the broad meanings conveyed by the literal language of the Constitution. Meaning is never exclusively derived from an archaeological dig into language divorced from the context of the times in which we live. According to Sunstein, it is not accidental that current protections against racial discrimination are a product of the 1950s; expansive protections of religious liberty came out of the 1960s; the ban on sex discrimination in the 1970s; and sharp constraints on affirmative action in the 1990s and 2000s. Nor is it an accident that newfound protection afforded to individual gun owners was rediscovered by originalists in the 21st century.

Sunstein observes: “Nothing here was inevitable and without contingent social forces and judgments ... radically different constitutional settlements would have emerged.”

Coda

I finished reading Sunstein’s essay and Gorsuch was confirmed. If I ever meet Justice Gorsuch, I may suggest that there was more to his cover story than he realized. Or simply say: “May the force be with you!” Perhaps he will have no idea of what I am talking about; but perhaps he will understand after all. n

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of

This article was published in the December 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with the title “May the Force ... How serendipity, Star Wars, Sunstein and constitutional law intersect.”