Nov. 22, 1926: The first Teapot Dome criminal trial begins

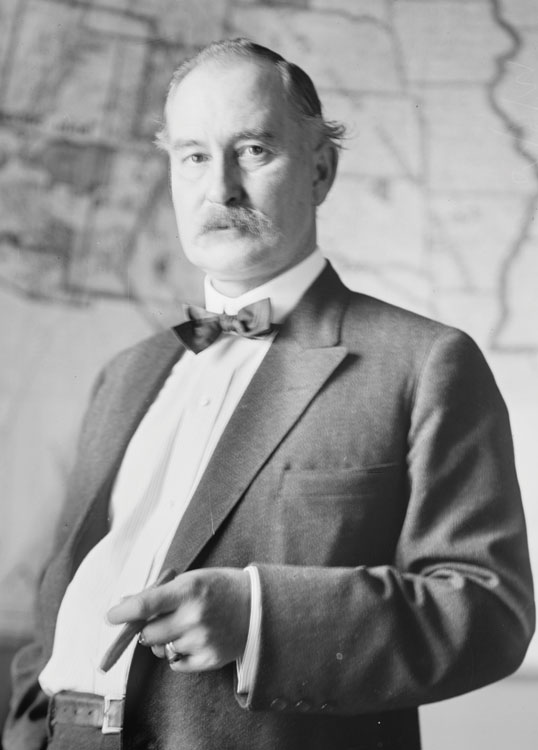

Harry Sinclair, multimillionaire oil mogul (left), and his counsel Martin Littleton attend the Teapot Dome hearing. Photo by Harris & Ewing/Library of Congress.

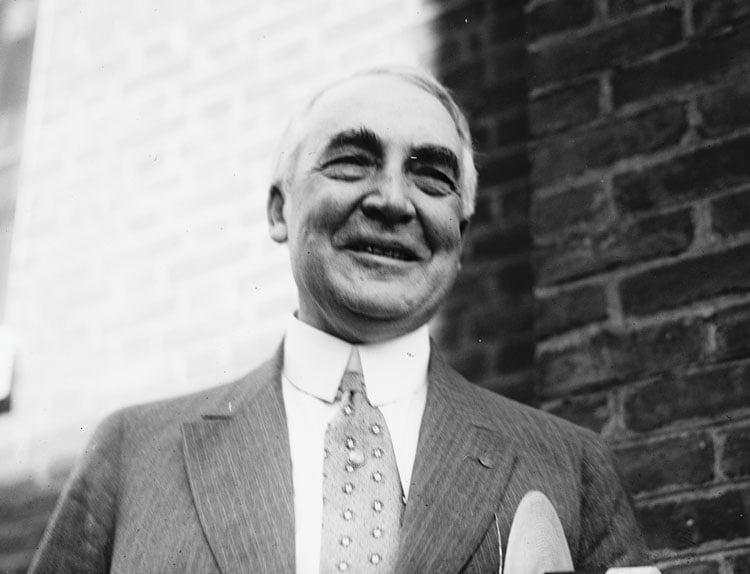

From the moment his name emerged from the infamous “smoke-filled room” at Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel as a possible 1920 Republican presidential candidate, Warren G. Harding was surrounded by rumors of corruption. His manner was pompous, his oratory prosaic; his qualifications, even as a U.S. senator from Ohio, were the subject of ridicule.

After winning 60 percent of the vote, Harding promptly took a vacation. When he finally returned, he salted his cabinet with a few well-known names: Andrew Mellon, Charles Evans Hughes and Herbert Hoover. But there also were cronies, and his secretary of the Interior, Senate drinking buddy Albert B. Fall, was one of them.

In 1920, the Senate had authorized the Department of the Navy to manage three vast-producing oil fields, two in California and one in Wyoming. But even before Harding was inaugurated in March 1921, Fall began lobbying Harding to wrest control over the reserves, and in May, Harding issued an executive order (No. 3474) that allowed just that.

Photo by Bain News Service/Library of Congress.

Almost immediately, Fall offered the two California reserves in Elk Hills and Buena Vista to Edward Doheny, a West Coast petroleum pioneer and an old friend of Fall’s. Under a no-bid, no-royalties arrangement, Doheny’s company, Pan-American Petroleum and Transport Co., agreed to build an oil storage tank, a refinery and a pipeline in exchange for exclusive control of 30,000 acres of government oil reserves. In November 1921, Doheny’s son, Edward Jr., arrived at Fall’s apartment bearing a black bag containing $100,000 in cash.

Meanwhile, Fall was negotiating with oilman Harry F. Sinclair for the Wyoming reserve known as the Teapot Dome. In April 1922, Sinclair’s Mammoth Oil Co. secretly agreed to build a pipeline and stock the Navy’s East Coast storage tanks in exchange for full control of the Wyoming field—another no-bid, no-royalties deal.

Almost immediately, details of the leases were revealed by the Wall Street Journal. In May, even as a Congressional probe was gearing up, Sinclair gave $269,000 in Liberty Bonds and cash to Fall’s son-in-law, M.T. Everhart, who delivered the bundle to Fall.

In hearings before an enraged Congress, oil and gas experts estimated that Fall had given away at least $100 million (about $1.4 billion in 2018) in government-owned oil for little or nothing. Navy officials argued that the arrangements protected the oil from “evaporation.”

Harding died from a heart attack in August 1923, but the whiff of scandal became so pungent that Congress intensified its probe. The first witness, Fall, denied any collusion with the two oil tycoons. But in January 1924, Doheny’s son admitted to Congress that he had delivered $100,000 in cash directly to Fall, and all hell broke loose.

Photo by National Photo Co. Collection/Library of Congress.

With Congress poised to authorize an independent counsel to investigate, President Calvin Coolidge jumped in, appointing two lawyers—Republican Owen Roberts, a Philadelphia lawyer; and Ohio Sen. Atlee Pomerene, a Democrat—to share the post.

Between 1924 and 1930, their Office of Special Counsel forged a record of mixed success. In the civil courts, they managed to return the reserves to the Navy, but criminal convictions proved hard to come by. Investigators were dogged by private detectives; prosecutors by inexplicably generous juries.

On Nov. 22, 1926, Doheny Jr. and Sr. began their trial with Fall on charges of conspiracy to defraud the government. After more than three weeks, a jury acquitted all three.

Fall faced similar fraud charges with Sinclair, but their trial ended in a mistrial when Sinclair was discovered using private detectives to monitor the jurors. Sinclair was subsequently convicted of contempt of court and sentenced to serve six months.

With Fall in precarious health, Sinclair was tried alone. This time, although Everhart testified about the Liberty Bonds delivered to Fall, the result was the same: Sinclair was acquitted.

But Everhart’s testimony returned to haunt Fall when he was retried. Fall was convicted and sentenced in 1929 to a year in prison with a $100,000 fine. When his case was rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court, Fall spent a little more than nine months in the New Mexico state prison.