The Anti-Terror Attorney: Andrew Hall's Life Is a Story of Survival Against Tyranny

Photo by Helen Ashford/Getty Images

One could say that for Andrew C. Hall, life has always been a battle against terror. Hall, founder of Hall, Lamb and Hall in Miami, is credited as the first attorney to win a case in the United States against a country labeled a state sponsor of terrorism.

Though he specializes in the trial of complex commercial cases, Hall has successfully sued Iraq, Libya and the Republic of Sudan—and brought in roughly $60 million, he says—for acts of terror that injured or cost American lives over the past two decades.

But then he’s dealt with terror from before he even was born. He almost didn’t make it past the first few hours of life.

Born in a coal cellar in Poland in the midst of the Warsaw Uprising during World War II, Hall weighed in at a couple of pounds. He probably wouldn’t have survived without an emergency blood transfusion from his mother.

Andrew Hall is now taking on Cuba’s Castros. Photo by Tom Salyer.

The very circumstance of his birth plays into the cases Hall chooses and the manner in which he pursues them. He uses whatever avenue is available to achieve his goal in making terrorists actually pay for the carnage they wreak. It often takes years and much maneuvering in both the courts and Congress before he sees results.

Hall says the longest fight was 11½ years on the Iraq case. “On the Libya case it was five years, and seven years for the USS Cole. Clearly these matters require constant perseverance,” he says.

“Other than the complexities involved,” Hall says, “terrorism litigation matters are not so dissimilar from the other areas of my practice. In fact, there is a synergy between these cases and other litigation matters in which I am involved, namely securities and complex commercial litigation. And while the cases are quite time-intensive, they have their own time schedule, allowing us to shift resources as necessary—which is what we do with all cases.”

James Cooper-Hill, a solo practitioner from Rockport, Texas, who has teamed up with Hall on numerous anti-terror cases, calls Hall “very simply speaking, the best trial attorney I’ve ever seen.”

Before taking on terrorist states, Hall made his bones helping defend John Ehrlichman, counsel to President Richard M. Nixon and a key figure in the Watergate scandal. Today, Hall is one of perhaps 10 lawyers in the country who sue foreign governments that terrorize American citizens, Cooper-Hill says.

Texas attorney James Cooper-Hill.

HANKERING TO HELP

In 1992, the Texan asked Hall to help sue the Iraqi government after its soldiers had kidnapped and tortured his client Chad Hall (no relation to Andrew), a civilian working to clear land mines on the Kuwaiti side of the border.

Hall agreed to assist Cooper-Hill simply because he felt it was the right thing to do. “Jim said there’s got to be something we can do for the guy,” who had been threatened with execution and even had weapons dry-fired near his head.

But the issue of sovereign immunity made it difficult to successfully sue Iraq. So where the courts were stymied, Hall pressed Congress, lobbying for legislation that allowed the case to proceed.

It may take a decade in some instances, but in the end, the terrorist states do pay up, Cooper-Hill says. “The first check I received was for $22.5 million,” he says. “We have not failed to collect in every case that we’ve handled, and Andy’s been right there, our principal arguer in the courtroom.”

Over the years, Hall has collected millions more for victims of torture. Just last year he recovered $13 million from the Republic of Sudan by tapping into its frozen assets on behalf of family members of the USS Cole bombing victims.

It takes a special kind of attorney to patiently let a case play out in court over long time periods, especially when all the cases are taken on a 100 percent contingency basis. Cooper-Hill says that “Andy is very persistent and very professional.”

In the beginning, before Hall’s team began reaping awards, says Cooper-Hill, his colleagues doubted the merit of such cases.

“Most lawyers wouldn’t have touched it,” he says. “All of them, when I first got into this, said, ‘You’ll never get paid. You’re wasting your time.’ They were mistaken. And part of it was Andy Hall’s tenaciousness.”

For Hall, “it was like quicksand. Once I stepped into it, I couldn’t walk away. There was just too much at stake.”

Hall is currently taking on Cuba’s Castro brothers. In February he filed an amended complaint in Villoldo v. Castro to force the Cuban government to arbitrate a wrongful death case brought by the surviving sons of a Havana man who committed suicide after his trucking company was nationalized. Gustavo Villoldo and his two sons, Alfredo and Gustavo, were systematically terrorized by the Cuban government, the case asserts.

Taking over the case from another firm, Hall’s approach is to go for a comparatively quick kill through international arbitration.

Andrew Hall as a small boy (left), with his mother, Maria, and brother, Allan. Photo courtesy of Andrew C. Hall.

LEARNING TO SURVIVE

Hall attributes his tenacity to the hardships he encountered as a Jew born in Poland during the Holocaust: “It kind of shaped my value structure, that value structure that translates into trying cases and doing what I do. … I was born in Warsaw in September of 1944. So that is a defining statement in and of itself.” He grew up with the stories of what his father, mother and older brother, Allan, had to do to survive.

Originally named Andrei Czeslaw Horowitz, he was born on Sept. 16, 1944—the same day it appeared as if the Soviets would rally behind the Polish freedom fighters who sought to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. Although they came within a few hundred yards of the Polish resistance that day, the Soviets simply looked on as the German army continued a killing spree that ultimately totaled some 200,000 civilians during the 63-day insurrection. Then the Germans systematically, block by block, leveled more than a third of the city in retribution.

As the Germans advanced on various parts of Poland, the family would hopscotch across the country —from Krakow to Lviv (in what is now Ukraine) to Warsaw and back to Krakow after the Germans leveled Warsaw in the months after his birth.

The family initially moved to Warsaw in February 1942. His father, Edmund Horowitz, spoke High German, as southern Poland was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. That ability (along with fake identity papers) allowed him to assume a new identity in Warsaw. He took the name Edmund Horskey while hiding in plain sight.

“He then posed, from that point on until the end of the war, as an Aryan,” Hall says. “My mother, who couldn’t pose that way, couldn’t get away with that—she was his Jewish mistress. My older brother became their illegitimate child.”

Almost as if he had nothing to fear, Horskey kept the family in close proximity to the enemy.

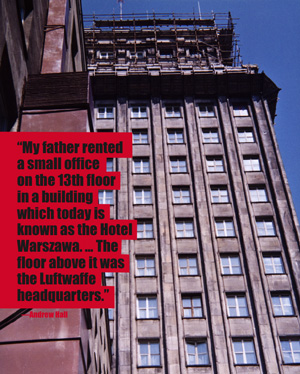

The Hotel Warszawa as it stands today, once headquarters of the German Luftwaffe. Photo courtesy of Andrew C. Hall.

“My father rented a small office on the 13th floor in a building which today is known as the Hotel Warszawa,” he says. “It still exists. Ninety-five percent of the old city was destroyed in the bombings, but that building made it. It was then an office building. The floor above it was the Luftwaffe headquarters.”

During the workweek his father would go off to his job as an accountant for a department store. Before leaving, he would lock his wife, Maria, and their eldest son inside a closet in the office.

“They would sit in the dark and they would crochet shopping bags all day long that they would sell on the black market,” Hall says. “And that was Monday through Friday. They couldn’t talk. They couldn’t make noise. They couldn’t go to the bathroom. They had to use a chamber pot.

“To give you an idea of how difficult circumstances were, on his birthday in 1944, they celebrated by making a cake out of used coffee grounds.”

In the summer of 1944, the Polish people orchestrated the revolt known as the Warsaw Uprising. The Polish Resistance sought to liberate the city from the retreating Germans. But when no help came from either the Allies or the Russians, the Germans struck back with a vengeance. Adolf Hitler ordered every inhabitant killed.

In the midst of the uprising it became too dangerous to live in the office building. The family moved to a bunkerlike coal cellar in another building. That’s where Hall was born.

Hall’s parents, Edmund and Maria Horowitz, on their wedding day. Photo courtesy of Andrew C. Hall.

MARIA’S STORY

Hall’s mother, who has since died, described the circumstances of her son’s birth during a videotaped interview she gave as a survivor of the Holocaust.

“I was there in the cellar with no help, no doctors, no water,” Maria said matter-of-factly. “I gave birth to my youngest. And this is a miracle that he is alive. First was cold. Then was no help. There was nobody to tie the umbilical cord. Later was a nurse. She says she knows something, but she knows very little. But God was with me. I’m alive. My child is alive.”

He wasn’t even 2 pounds, his mother said, adding that she was so malnourished that she couldn’t nurse him. His parents improvised with sugar water and the milk from a goat someone had found. They warmed the concoction in a tin can, but the baby kept regurgitating it.

For the next 36 hours they were uncertain whether he would live. Every 10 minutes or so she would try to spoon-feed him in the hopes that some food would stay down. He survived the critical first days only to develop pneumonia.

A doctor who no longer had an office suggested a blood transfusion from mother to child. He had no means of testing the blood types, and if they were incompatible, the child would die.

“Without testing the blood, they took a big ampoule from me and they injected the child,” she continued in a monotone. “If it’s OK, if he will be able to survive, so he’ll live. If not, nothing to lose because he was dying anyway. And it helped, twice broke the pneumonia this way.”

Hall and mother Maria, later revisiting Poland. Photo courtesy of Andrew C. Hall.

GOING UNDERGROUND

Just two weeks after Hall’s birth, the family had to flee Warsaw ahead of more German troops. They planned their escape through the sewers, the same network of underground canals used by the Polish resistance. On the precarious journey they needed to slip past the Germans, who had orders to shoot on sight any Pole. Hall’s parents debated what to do with a newborn whose cries could jeopardize their lives.

“And my husband wanted to take the older child and we shall leave the little one,” Maria said. “He was very sickly. He was very small. He was tiny and we didn’t even expect him to live for another day or so. And the Germans were coming and we wanted to go escape this way.

“But I looked at my little boy—as little as he was, as sickly as he was—I said, ‘My God, he is alive, how can I do that? You go with my older son and I’ll stay with him. And whatever will be with him will be with me. But I won’t do it.’

“And this stopped my husband. He didn’t want to part with me, that we were all together trying to survive.”

They ended up in Krakow, where Horskey became the minister of insurance until the communist takeover in 1946. The communists promptly arrested him for treason. Fearing the next step was to make the family “disappear,” Hall’s parents decided to smuggle their sons out of Poland and into Germany, where they would join a group going to Palestine.

But the baby again fell ill and ended up in a hospital in Munich. His brother resorted to writing to his mother’s cousin in Palestine to come get them.

Meanwhile, the communists had convicted Horskey and sentenced him to death. The Poles thought he had died in prison, but he faked his death and—with help from the British, who exchanged a dead body for him alive—his father was smuggled out, Hall says. His parents then began a yearlong search before they could find their children; like Horskey, the children changed their names as they traveled.

The search ended in Munich, where out of pure happenstance the cousin from Palestine ran into Hall’s parents while they were at a café contemplating where next to look.

Hall was told that he initially didn’t recognize his father when they were reunited. His father recounted the episode in his self-published book about the war years, Was I A Spy?: “As soon as Andrew saw his parents, not recognizing his father, he asked him in Polish, ‘Mister, give me a drink of milk.’ ”

The book both begins and ends with the family fleeing Europe for the United States after the war. Immigration documents provided by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society indicate that “Admund Horski,” who listed his occupation as a “government official,” his wife and two young sons arrived in New York City on Jan. 12, 1947. They flew in from London under the aegis of the Polish Embassy, according to the documents. Once in the States, the family changed names again, this time to Hall.

Hall’s early struggle simply to survive imbued him with a fighting spirit that lives on in his practice of law.

When he began suing foreign countries for their terrorist acts against American citizens, he initially ran into resistance with the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976, which protects nations from being hauled into court in most circumstances.

Hall sought to carve out an exception. He lobbied the U.S. Congress and succeeded in getting the law changed in 1996 to allow civil lawsuits against seven designated state sponsors of terrorism—Cuba, Iran, Iraq, Libya, North Korea, Sudan and Syria. And Hall later helped lobby so that payment for his client would be included in the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act, which President George W. Bush signed into law in November 2002. That act allowed the plaintiff to collect on the judgment through U.S. Treasury funds that would later be taken from frozen assets of the individual defendant terror states.

Such was the case with Sudan and the bombing of the USS Cole. On Oct. 12, 2000, two smiling terrorists in a motorboat blew a 160-square-foot hole in the hull of the U.S. Navy destroyer as it refueled at the port in Aden, Yemen. The blast killed 17 American sailors and injured 39.

Hall was part of a team that successfully sued Sudan on behalf of those who died in the bombing. He helped win a judgment of some $8 million for surviving family members in 2007, increased to around $13 million with prejudgment interest. Frozen Sudanese assets were released to satisfy the award.

In the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, 17 American sailors were killed and 39 wounded. Last year, Hall helped win a $13 million judgement from Sudan for the families of the victims in what he calls his toughest case. Now he is helping the walking wounded from the bombing. Photo by Lyle G. Becker/AFP/Getty Images and AP Photo.

TACKLING NEW CHALLENGES

Today, Hall is helping the walking wounded from the Cole bombing. They are sailors like Rick Harrison, who declined to be evacuated from the ship despite sustaining permanent injury to his knees, lower back and eardrums. As the ship’s fire marshal, Harrison remained at his post helping to extinguish the fire after the explosion.

“While he remained on board, Mr. Harrison inhaled toxic smoke in a room where wiring was burning and later developed a lung condition as a result,” reads a complaint filed last October in federal court in Washington, D.C.

Harrison, who has undergone numerous surgeries, has post-traumatic stress disorder and is deemed unemployable by the Department of Veterans Affairs. He is one of nine sailors and one spouse seeking reparations from the Sudanese government, which allegedly helped al-Qaida launch the attack.

Hall says, “The [original] Cole case was the toughest in terms of piecing all of the intelligence together. But each one brings its own set of challenges, in large part due to the constant changing of the law in this area.”

Yet Hall finds neither the changes nor the challenges to be hurdles that might discourage him from further cases.

“This is exciting work,” he says. “I have no intention of slowing down.”

Last updated Aug. 24 to correct the spelling of Adolf Hitler’s name.

Siobhan Morrissey is a lawyer and freelance writer in Miami.