The Cemetery Sea

Illustration by Stephen Ravenscraft

There are a thousand ways to die on the Bering Sea, and it seemed like all 1,000 hurtled toward the Alaska Ranger at 2 a.m. that Easter morning.

Massive waves—skyscraper-size and Bible black—smashed the Ranger. Snow squalls blasted the deck. A storm gripped the 203-foot mackerel boat 120 miles off the Alaskan coast. Waves flooded the rudder room, rushing past watertight compartment doors.

“Catastrophic hull failure!” an officer shouted.

The electricity cut off. Suddenly, the engine locked into reverse.

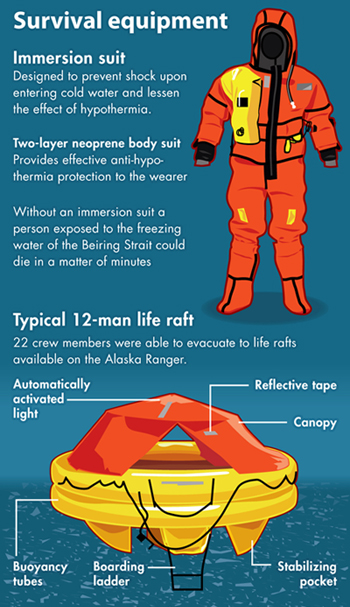

As the crew scrambled into neoprene survival suits, they peered into the wheelhouse where Capt. Peter Jacobsen called maydays into the radio. The fishmaster—a mysterious officer from Japan who directed them toward fertile fishing grounds—sat in the wheelhouse smoking a cigarette, staring straight ahead. His survival suit hung unzipped off his shoulders.

He expects to die, the crew realized.

A U.S. Coast Guard cutter and the Ranger’s sister ship, the Alaska Warrior, were on their way in a matter of minutes. But Jacobsen knew they wouldn’t get there in time for all 47 souls to stay aboard.

“Abandon ship!” Jacobsen ordered.

The life rafts were frozen in icy cocoons. The first raft the crew was able to lower shot far away because the ship was moving backward.

A ghostly blue glow shimmered across the crashing surf: phosphorescent algae. Hoping they could find a raft in this dim light, crewmen leapt into the Bering and frigid water poured through ripped seams and holes in some of their survival suits.

The suit assigned to Byron Carrillo—a short, compact man—seemed several sizes too big for him. The stint on the Ranger was his first time on a boat. He had worked for years at day labor jobs in Los Angeles while his wife worked full time at the city’s airport. He was thrilled to land a full-time job on the Ranger cutting fish—pay that would one day help move his wife and two children to a safe neighborhood.

Ranger engineer James Madruga floated near Carrillo for hours as debris sloshed around them. “I’m so cold,” Carrillo moaned as his leaky suit filled with icy water.

Capt. Jacobsen and first mate David Silveira died guiding rescuers to the wreck. Three other men also died that night.

Interactive graphic by Stephen Ravenscraft

ARBITER OF DISASTER

Jim Beard

Photo by Brian Smale

The Coast Guard rescuers—who were awarded Air Medals for courage against overwhelming odds—did not know that just three months before the March 23, 2008, sinking, a Coast Guard lieutenant inspected the Ranger and declared it unsafe to sail. A civilian inspector employed by the Coast Guard overruled him.

That inspection procedure for commercial fishing vessels is just one oddity of maritime law—a universe where ancient tradition, the $10 billion U.S. fishing industry and international intrigue frequently collide.

The U.S. Department of Labor has ranked commercial fishing as the deadliest job, and the Bering Sea as its most lethal workplace. And to a great extent, maritime law governs both.

More than 400 fishermen have died since 1999, according to an investigation by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Currently, inspections of vessels like the Ranger are done under a voluntary compliance program that critics call de facto self-policing by the industry. A 2006 Coast Guard study estimates 127 fishing vessels will be lost annually until safety regulation becomes more stringent.

A commercial fisherman expects to dodge death and maiming daily, just like he expects to have his morning coffee. Crab pots weigh 700 pounds empty—twice that full. Wind whips heavy nets and pots across decks as sailors desperately try to control them. Below deck, men wield saws and knives over slippery fish while the floor underneath them bucks like a bronco.

Sooner or later, an experienced maritime lawyer is as necessary to the commercial fisherman as foul weather gear. In the bars along the wharfsides, attorney business cards are tacked to the walls with reviews from current or former clients.

Lawyers representing commercial fishermen have a potent weapon that landlocked attorneys lack: the Jones Act. The 1920 law was enacted when supremacy on the seas was key to U.S. prosperity. It allows commercial shipping workers to collect far more in damages than earthbound injured workers get via workmen’s comp.

Here risk meets reward, untamed by tort reform. And the free-spirited lawyers who help enforce the Jones Act are unapologetic about the service that they feel they perform.

“It’s reform by litigation,” says Seattle maritime attorney Jim Beard, a founding partner of Beard, Stacey, Trueb & Jacobsen. He represents the family of a Ranger crewman who died. “Shipowners may like to think of us as pirates who use complaints instead of muskets and swords. But insurance companies don’t like paying big settlements. After a big payout, they can demand fishing vessel owners make their ships safer or lose their insurance. And shipowners don’t want to lose the chance at a million-dollar season.”

The wreck of the Alaska Ranger triggered an international federal investigation and 21 lawsuits against the Ranger’s owner, the Fishing Company of Alaska. Survivors and families of the dead filed for wrongful death, personal injury and loss of enjoyment of life.

The shipowners, of course, fight back. And the owner of the Alaska Ranger, a female fishing mogul by the name of Karena Adler, is no exception.

Adler answered the mounting lawsuits with a bold move. She asked a federal judge to limit her liability to zero under the antique yet still valid “end of the voyage rule,” an 1851 law created for wooden sailing ships—bereft of radar and radios—left to luck’s mercy. Less poetically known as the Liability Limitation Act, the law allows an owner to limit liability to the value of the ship and cargo at voyage’s end should a disaster strike that is beyond the owner’s control. The Ranger ended its voyage at the bottom of the Bering. It had no value. By that standard, the Ranger survivors and the families of the dead would get nothing.

The FCA’s insurance company began offering settlements of $25,000 to survivors who stepped directly into a life raft, $35,000 to those who had to swim to a raft and $75,000 to those who never made it to a raft and were pulled from the sea.

George Knowles

Photo by Brian Smale

But the act only applies if an owner has not been negligent, which was an open question in regard to the Alaska Ranger. And the FCA owned six other profitable ships, as well as fishing rights worth tens of millions—all vulnerable to collection should the company be shown negligent. And this is where lawyers like Beard earn their wharfside reputations and the fishermen’s trust.

Whether he presented his case to a judge or sat at a table with a mediator and the FCA’s counsel, Beard knew that he needed to present a detailed, visceral, almost cinematic picture of each of his client’s final hours on the Ranger.

Beard and other maritime lawyers collected evidence the Ranger was in slipshod condition to convince the court that the owner was negligent. And he began interviewing each client, harvesting harrowing and haunting details.

“Lawyers have to be good storytellers,” Beard says. “You can’t bore a judge, a mediator, the opposing counsel or a jury to sleep and expect to serve your client well.”

DON’T ROCK THE BOAT

Commercial fishing generates plenty of safety paperwork, whether or not anyone reads it. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency observers sail with commercial boats like the Ranger to ensure no quotas or fishing regulations are violated. Observers write safety checklists before a ship sets sail. Federal observer Gwen Rains wrote that the Ranger’s watertight seals seemed battered and corroded. Her last report listed numerous safety violations.

“Things happen at sea that would cause a massive OSHA raid if they happened on soil,” she says. “I wonder … if the Coast Guard or FCA ever read [my] report.”

The answer is easy.

Steve Fury

Photo by Brian Smale

“The Coast Guard normally never sees the federal observers’ reports, and I honestly don’t know whether the shipowner looks at them,” says Capt. Mike Rand, head of the Coast Guard inquiry into the Ranger’s sinking.

Three months before the Ranger sank, the Coast Guard gave it a drydock inspection in Japan. Lt. Prudencio Tubalado crawled throughout the hull and found corrosion on the walls. He decided the Ranger was not seaworthy. He gave his notes to the senior inspector, Martin Teachout, a civilian employee of the guard. Teachout declared the Ranger in good shape, though he said several repairs should be made once it sailed back to Alaska.

Capt. Mark Hamilton oversees all of western Alaska’s coastline, rivers and waterways. “I wouldn’t say they disagreed; I would say they saw different things and Mr. Teachout deconflicted their findings,” Hamilton says.

Coast Guard information officer Sarah Francis, an engineer by training, says “quite a bit of work” was done on the Alaska Ranger in Japan. Though there were outstanding fixes needed, none of them made the ship unsafe to sail, she says.

“Crewmen don’t want to complain about safety violations for fear of being blackballed,” says Seattle maritime attorney Steve Fury of Fury Bailey. A Stanford and Harvard Law graduate, he represents Capt. Jacobsen’s widow against the FCA.

Fury’s dad was a logger, “the first guy in Washington state to use a power saw.” His father was killed in Indonesia when a “widowmaker”—the rotten top of a towering tree—broke off and crushed him. Fury understands why men choose dangerous careers.

“A deckhand fishing for king crab and black cod can make a six-figure income,” Fury says. “Workers gutting and cutting fish in the bowels of a boat usually earn an hourly wage, so they aren’t getting a paycheck when the nets come up empty. But they see fishing as a job with a career path.”

Beard puts it another way.

“Fishing is like a slot machine—always just enough payoff to keep a sailor coming back tomorrow,” he says. “It’s like lawyering, except I gamble my house; they gamble their lives.”

WHO’S AT THE HELM?

John Merriam

Photo by Brian Smale

That the hull of the Alaska Ranger was battered came as no surprise to Seattle solo attorney George Knowles, who represents eight Ranger survivors. One of his clients, Ryan Shuck, tells a story that not only offers some explanation for the vessel’s condition but raises serious questions about who, exactly, was running the ship.

Jacobsen, the ship’s heroic skipper, was actually a last-minute replacement for the Ranger’s regular skipper, Steve Slotvig. On a previous trip, Shuck has testified, Slotvig had a screaming fight with the ship’s fishmaster, Satoshi Konno.

So aloof was Konno that most of the crew had no idea he spoke English until he began shouting obscenely articulate insults at Slotvig during their heated exchange. Shuck and other crewmen testified at a joint Coast Guard and National Transportation Safety Board inquiry that Konno had apparently ordered Slotvig to sail the Ranger through pack ice 6 inches thick. Witnesses said the Ranger’s hull screeched and shuddered. Shuck describes the Ranger ricocheting like a pinball between ice chunks.

Slotvig admitted he often let Konno pilot the Ranger.

“Konno was a Japanese citizen and should not be giving orders to the captain,” Knowles explains. “U.S. law demands that American commercial fishing vessels be controlled by an American captain, first mate and engineer.”

Konno apparently went down with the Ranger. His body was never recovered.

Knowles, a Navy man’s son, started his maritime legal career defending insurance companies from “the sort of people I represent now.” It was back in the days when TV stations got news flashes via telex machines. The telex in Knowles’ office would ring wildly and shoot out tape filled with news of mutinies, injuries, shipboard fires and cargo damage off the Washington coast. He ran to the docks, tape in hand, to negotiate settlements.

He even owned a commercial fishing boat, the Grizzly. Crab boat crews earn a daily wage and a portion of the profits from their catch so they hate leaving the crab pots, even to sleep or shower.

“I bought beat-up sofas from Goodwill for the Grizzly’s mud room—where men can sleep with their clothes covered in mud, fish scales, slime, oil, salt and stinky guts,” Knowles says, eyes sparkling at the memory.

Knowles reckons the Ranger cases, once ended, will involve 40 depositions of eyewitnesses alone. “Then you have experts and witnesses like naval architects and engineers, since the exact cause of the hull failure is still a mystery,” Knowles says.

But for federal investigators, an even more nagging question may be who, exactly, owned the Alaska Ranger. At stake is millions in fines and a potentially sticky international situation.

MYSTERY WOMAN

As Beard and Knowles combed their clients’ memories of the fatal night, they also wondered whether they would ever catch a glimpse of the FCA’s mysterious owner. In all their years in Seattle, they had never seen her in person. Sailors know her mainly through the holiday treats she sends each year: Christmas stockings stuffed with chocolate bars and Playboy. Many FCA office staff say they have never laid eyes on their reclusive boss, Karena Adler, nicknamed the “Howard Hughes of fishing.”

At least, she claims to be the FCA’s owner.

Adler, now 56, attended school in Japan, where she married a Japanese tycoon 29 years her senior. When they divorced in 1984, she used the settlement money to build the FCA. The Seattle Times reported Adler swept into an Anchorage auction in 1991 wearing snakeskin boots and a long fur coat. She bought the Ranger and accrued a seven-ship fleet.

North Pacific Fishery Management records show the FCA’s annual catch is worth $30 million. FCA fishing rights, issued by the federal government, are potentially worth an equal amount.

But many feel there is good reason to question whether the FCA is actually owned by Adler—or controlled by commercial fishing interests in Japan.

First, there is the puzzling authority that fishmaster Konno appeared to have over the captain of the Alaska Ranger—evidenced by their argument on one of the vessel’s last voyages.

Moreover, the FCA’s fleet often gets repairs and rehabs in Japan, baffling inspectors who say Japan is typically far more expensive than China or the U.S. for such work.

SOURCE: U.S. Coast Guard. Graphic by Stephen Ravenscraft

The FCA does not have a website. At one time, Anyo Fisheries Co, a Japanese concern, listed FCA as a partner on its website. As late as March, the site held photos of what was FCA’s entire seven-ship fleet—including the Alaska Ranger. But Anyo’s site has been taken down.

The Maritime Administration—a branch of the U.S. Department of Transportation—collects proof of whether a company is American-owned. But that proof, according to Pacific Fishing (PDF) magazine, can consist of nothing more than sworn affidavits from an American who claims to be the vessels’ owner. No further proof is demanded.

The question of ownership is not unimportant. If a Japanese entity actually owned the FCA, then it would be liable for up to $100,000 in fines for each day each FCA vessel fished in U.S. waters. Vessels must be 75 percent owned by U.S. citizens to be allowed to fish within 200 miles of American shores.

No one answered the continually ringing telephone during the numerous times an ABA Journal reporter called the FCA in search of Adler. The company’s Seattle attorney, Lane Powell shareholder John Neeleman, did not respond to requests for an interview. Capt. Hamilton says there is a federal investigation into whether foreign nationals owned or controlled the FCA. If it turns out they did, it may be a different ballgame for Beard and others representing crew members and their families.

PRICING LIFE AND LIMB

Before working for sailors in court, big, tall, bearded Jim Beard worked on an oyster dredge to pay college tuition.

“Sometimes I made more as a deckhand than my mom made as a schoolteacher,” he says.

His office offers a sweeping view of Seattle’s Fishermen’s Terminal: docks, trawlers the size of small towns, cranes hefting mammoth nets, and tiny boats selling silver salmon and lingcod off decks crusted with salt.

His client list reads like a deadly roll call of a lost fleet: Arctic Rose, Galaxy, Vestfjord, Aleutian Enterprise, Pacific Apollo and Pacesetter.

His website ticks off settlements and the fishing profession’s toll: $3.5 million for a brain injury, $1.9 million for fingers and part of a hand lost cleaning a bait chopper. For the sailor, such settlements can buy a dream: a boat of one’s own, retirement or even—as in the case of one sailor—a manicure shop.

Not every injury can be blamed on the shipowner or the sailor. If a no-fault injury sidelines a sailor for a while but does not end his seagoing career, “maintenance” is a remedy. Maintenance pays daily expenses until the sailor can go back to work. Seamen’s unions in the 1950s negotiated a maintenance rate of $8 per day.

“That’s where it stayed for almost 50 years,” says Beard’s colleague, John Merriam, who has a small solo office nearby.

“The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit enforced the $8 a day rate. I successfully argued to the Washington Supreme Court that it should not follow the federal 9th Circuit.”

He got his client a few hundred dollars for a damaged ankle. Merriam won a few dollars as a contingency fee.

Merriam represents the family of the Ranger’s chief engineer, who died after abandoning ship. Fury and Beard admire him as an attorney who tilts at windmills and sometimes wins. But they wonder how he survives as a solo. Fury has two other attorneys at his firm as well as a paralegal. Beard has an entire team of lawyers.

“Solo maritime work is extremely hard,” confides Merriam, who has a slight limp from a motorcycle accident. “I almost lost my house one year.”

Before Beard confronts a multimillion-dollar fishery in court, his team marshals batteries of expert witnesses. Suppose a fishing company argues against pain and suffering compensation for a drowned man’s family on the grounds that some medical studies show that asphyxiation causes euphoria. Beard is prepared with a medical expert who can describe the trauma of drowning and how, psychologically, time seems to slow down, prolonging the terror.

The strange math of crunching pain and fear into a dollar amount involves art as well as evidence. Beard wrote a letter to the mediator in the Alaska Ranger case, relating one client’s memory of the ship sinking. He tried to get the mediator and the FCA attorney sitting in an office to imagine snow scouring their skin, gales roaring and cold waves lashing their knees as the Ranger deck slants violently into the Bering Sea. The crewmen were slammed into the rail. Capt. Pete told them to abandon ship, but they could not spot a raft near the ship.

The normal human impulse is to cling to a sinking ship rather than leap into the vast, dark and roiling ocean. Beard’s client knew some of his friends would die that night—he might die, too. He gathered a few of them close and led them in a prayer. Then he leapt from the deck into the raging waves.

Sometimes it is hard for maritime lawyers to explode the stereotype jurors and even judges may have of fishing crews. People figure these guys take risky jobs to hide from busted marriages or arrest warrants. There are problems with drugs and drinking, problems with women, the stereotype goes. Maybe there’s a problem with everyday life and finding anyone to care about them.

Something near Beard’s office defeats that stereotype.

HONORING THE DEAD

The Seattle Fishermen’s Memorial is a stone column topped by a bronze fisherman and encircled by low walls. Wood-framed photos of young men who died at sea are propped against the walls. The Katmai—a 93-foot American cod boat—sank only a few days earlier, killing seven, but someone had already fastened a photo of the Katmai to one wall.

A wreath of creamy white roses with a purple ribbon emblazoned “Galaxy” adorns the column. Four men died after an explosion and fire on the Galaxy. The captain fought his way into the burning wheelhouse to trigger an automated mayday. He suffered severe burns on 10 percent of his body.

Pink and coral rosebuds encircle the column base, a tribute to the Arctic Rose (all 15 crewmen and captain dead). Nearby sits a stone tablet engraved:

If tears could build a stairwell and memories a lane

I’d walk right up to Heaven and bring you home again.

The tablet is signed in Magic Marker: Mom, Dad, Sis.

One could imagine similar sentiments being left by the widow and two children of Byron Carrillo, who was on the Ranger only a few days before he died. Carrillo was thrilled to get steady work.

Petty Officer Alfred Musgrave testified before the Marine Safety Board that he had rescued three Ranger survivors who were wrapped in wool blankets in his helicopter. Then he spotted Carrillo precariously flopped across the rescue basket the copter was hoisting from the sea. (See rescue footage from the Coast Guard, Popular Mechanics and the Seattle Times.

“He would be in the basket, and then a wave would wash over and he’d be back out,” Musgrave recalled, adding that Carrillo’s swollen survival suit prevented him from getting a secure position in the basket. “He looked terrified.”

Carrillo slipped. Musgrave was able to grab his legs for just a few seconds before Carrillo plummeted 40 feet back into the ocean. The copter was dangerously low on fuel and had to leave. The strobe light on Carrillo’s survival suit cast a warm glow on him through the murk and snow. At the hearing, the daring Coast Guard rescuers became tearful as they described Carrillo, floating face down in the Bering Sea, where he died alone.