The Dream Bar: Some Children Illegally Living in the United States Grow Up to Want to Be Attorneys

Jose Manuel Godinez-Samperio is a valedictorian, Eagle Scout and scholarship winner, he brought the first case seeking bar admission. Photo by Doug Scaletta.

Bar admissions candidate Jose Manuel Godinez-Samperio was almost a textbook example of the perfect bar admissions case. Despite an economically disadvantaged background, Godinez-Samperio went on to become the valedictorian of his high school, a National Honor Society scholar and an Eagle Scout. He later won multiple scholarships to the New College of Florida and Florida State University’s College of Law, where he did pro bono internships at Gulf Coast Legal Services and the FSU Center for the Advancement of Human Rights.

When Godinez-Samperio, 26, applied for admission to the Florida Bar in 2011, he included letters of support from three of his former law professors, as well as the general counsel of the New College. When his application turned into a court case, amicus briefs filed on his behalf came from several past presidents of the American Bar Association, and he was represented by Talbot “Sandy” D’Alemberte, a former ABA president who taught Godinez-Samperio at Florida State.

Why would such a qualified applicant end up in court? Because, unlike any known Florida bar hopeful before him, Godinez-Samperio is not legally in the United States.

When he was 9 years old, his family came to the U.S. from Mexico legally on tourist visas; they stayed after the visas expired. Raised in the United States, Godinez-Samperio has American ambitions, but not the legal status he needs to pursue them. Unsure whether Florida law permits—or even contemplates—bar admission for Godinez-Samperio, the Florida Board of Bar Examiners petitioned the state supreme court in December 2011 for an advisory opinion: “Are undocumented immigrants eligible for admission to the Florida Bar?”

It was an issue of first impression in any state, though two others have since taken it up.

The California Supreme Court is expected to hear oral arguments on the admission of Sergio Garcia, whose family first entered the United States “without inspection” when he was a toddler. And in New York, Cesar Vargas—whose family entered without inspection when he was 5—submitted his application for admission in October. In anticipation of similar challenges, Vargas, 29, added letters of support from prominent legal and political figures. All three men have been open about their immigration status.

More such cases may be coming. According to estimates from the Pew Hispanic Center, “11.2 million unauthorized immigrants were living in the United States” in 2010, up nearly 3 million from a decade earlier.

Though the center doesn’t break down which of these people came to the United States as minors, it estimated last August that 1.7 million would benefit from President Barack Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which offers two-year work visas for young adults who were brought to the U.S. before age 16 and meet certain other requirements.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement offices in immigrant-rich population centers reported being flooded with applicants. Godinez-Samperio and Vargas have both applied to the program; Garcia, born in 1977, is too old to qualify.

The number of young adults without legal immigration status has become large enough that the DREAM Act, which would give citizenship or lawful permanent residency, aka green cards, to many of them, has become a perennial political issue over the past decade (the acronym stands for Development, Relief and Education of Alien Minors). Though the idea has some bipartisan support—Republican U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida drafted a version that did not include a path to citizenship—it taps into the heated political issue of immigration and has never gotten through Congress.

The legislation may be stalled, but it has given its name to the DREAM Bar Association, a loose confederation of would-be attorneys who are likely to benefit if the act is passed. Godinez-Samperio and Vargas both count themselves as members; Godinez-Samperio is a co-founder.

The association has filed amicus briefs in the California and Florida cases, using counsel from the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Godinez-Samperio estimates that the group has a handful of members around the United States, including law students and undergraduates; Vargas says it’s about 20.

Godinez-Samperio says he didn’t know anyone else in his position when he co-founded the DREAM Bar Association a few years ago. These days, its ranks include a few law school graduates and many more college students.

Though he, Garcia and Vargas all happen to be Mexican nationals, Godinez-Samperio emphasizes that the bar association is not limited to Latinos. Indeed, while Latino interest groups filed in support of admission in both cases, the association’s amicus brief supporting Garcia was joined by the Asian Pacific American Legal Center and the Asian Law Alliance.

After an internship with the Kings County DA’s office, Cesar Vargas hopes to become a prosecutor or a judge advocate general in the Marine Corps. Photo by Len Irish.

ELEVATING THE ISSUE

Garcia, the California applicant, was sworn in as an attorney for about two weeks before he received a notice from the state bar that his admission was in error. He had hoped to launch a solo general practice. Instead, he went back to nonlegal work in the Northern California Sierras. His attorney, Jerome Fishkin of Walnut Creek, Calif., says this includes work as a beekeeper.

The state supreme court invited briefing from California Attorney General Kamala Harris and the U.S. Department of Justice when it started Garcia’s case last May. Unlike Godinez-Samperio, Garcia was initially recommended for admission with no reservations, although the California Committee of Bar Examiners did notify the supreme court that Garcia was not a lawful U.S. resident. The court, which is the ultimate authority on bar admissions in California, ordered the committee to show cause for why Garcia should be admitted.

Garcia first came to the United States as an infant, went back to Mexico at age 9 and returned at 17. A twist in Garcia’s case is that his status may be legalized. He is eligible for a green card through his father, who is a lawful permanent resident under the 1986 amnesty law. Garcia has been approved since 1995, but due to the limited number of spots for Mexican nationals, he’s been waiting about half his life for the green card to be available.

Vargas, too, entered without inspection as a boy. He grew up in Brooklyn and attended the City University of New York School of Law. Originally he hoped to become a judge advocate general in the Marine Corps or work as a prosecutor, something he enjoyed when he interned with the Kings County district attorney’s office. Without citizenship, however, both careers may be closed to him. He’s also thinking about starting his own firm.

Vargas, like Godinez-Samperio, is a DREAM Act activist; he has testified before Congress and has even started a lobbying organization, the DRM Capitol Group, to advocate for the law. He says that his activism was inspired by the example of other people in his position, and that he hopes he can help others by example.

“It was definitely a tactical decision to go public because I wanted to put the spotlight on [immigration and the DREAM Act],” Vargas says. “I’m using my story to elevate an issue.”

Jerome Fishkin represents Sergio Garcia, who is eligible for a green card and was sworn in as an attorney before the error was noticed. Photo by Eric Millette.

CHARACTER AND FITNESS

Although no state bar has considered whether to admit a candidate present in the United States illegally, there is precedent on bar admissions for legally present noncitizens. In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in In re Griffiths that the Connecticut Bar Association had violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment when it required citizenship for bar admissions.

Various state high court rulings have echoed that and, in some cases, extended eligibility to lawful permanent residents. However, state bar admissions bodies are free to ask about immigration status, and 22 of them do.

Federal courts have very little authority over the states’ bar admissions (or attorney discipline) decisions: They may stop equal protection violations, but any other regulations must have a relevant connection to the practice of law. A 2004 case in the San Francisco-based 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Gadda v. Ashcroft, found that federal law does not pre-empt the California Supreme Court’s authority to discipline attorneys, even for an attorney who practices only in immigration and federal courts.

In 2005, however, the 5th Circuit at New Orleans upheld a Louisiana rule forbidding aliens with nonimmigrant visas from taking the state bar exam in LeClerc v. Webb.

And in 2006, a federal court in Georgia found that the state’s Office of Bar Admissions did not violate the equal protection clause by requiring immigration status documents from noncitizens. That case, Godoy v. Georgia Office of Bar Admissions, was cited by the Florida Board of Bar Examiners when it asked the state supreme court for an advisory opinion on the admission of Godinez-Samperio. Though Godoy had no precedential force in Florida state courts, it did raise the issue of unlawful presence in the United States: “An applicant’s willingness to maintain an unlawful residence in the United States, like his ongoing participation in other illegal activities, has an undeniable bearing on that applicant’s character and fitness to practice law.”

Though the character issue was raised at the beginning of Godinez-Samperio’s case, he and D’Alemberte emphasize that the board ultimately gave Godinez-Samperio a clean character and fitness evaluation.

“I think the bar wanted to fully investigate Jose’s circumstances to see whether there were any character problems,” says D’Alemberte. “Several months ago, they sent us notice that they had completed character and fitness and there were no [problems]. The only issue was whether there should be a bright line against an illegal immigrant being a member of the bar.”

D’Alemberte adds that “you could convert” immigration status into a character issue, but that strikes him “as a little bit bizarre.”

Like all DREAM Act-eligible young adults, Godinez-Samperio was brought to the United States as a minor; to go back to Mexico when his visa expired would have required him to leave his home and family at the age of 9.

In Garcia’s case, too, character has not been a serious issue. The California Committee of Bar Examiners found no moral character problems before recommending him for admission.

“The investigation he underwent was more thorough and longer and more detailed than I’ve seen in any other investigation in 20 years of doing this work,” says Fishkin, Garcia’s attorney.

Fishkin emphasizes that Garcia has made an effort to stay in compliance with the law. “Moral character gets down to ‘What did you do?’ ” he says. “He pays taxes, he works, he’s registered with ICE. When you look at what he’s done, he has made every effort to obey every law possible in doing this.”

The two amicus briefs submitted in opposition to Garcia’s admission disagree. Both emphasize that Garcia is unable to uphold the law because he is present in the United States illegally. (One of the two authors, lawyer Nicholas Kierniesky of Millville, N.J., declined to comment.)

According to amicus Larry DeSha, a retired California state bar prosecutor, being in violation of the law means Garcia cannot swear to uphold the law, as all California attorneys must do. DeSha doesn’t argue that this indicates a lapse of moral character, but he says Garcia would be in violation as soon as he took the oath—and again as soon as he served penalties for being in violation of it.

“Moral character is not the issue. It’s a different thing from violating the law,” DeSha says. “[The law] says the first offense probably wouldn’t be very heavy, but if you’re illegal you’d be in violation immediately again.”

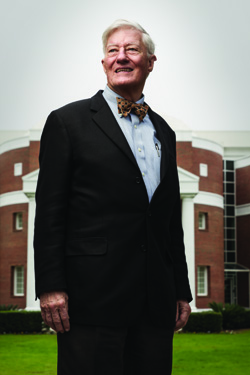

Former ABA president, Sandy D’Alemberte, taught Godinez-Samperio at Florida State and now represents him in his quest for bar admission. Photo by Matthew Coughlin.

DISPUTES OF LAW

DeSha also argues that admitting Garcia would pose a risk to the public because Garcia is not eligible to work in the United States. Such an attorney, he says, would be exposing clients to criminal prosecution just for hiring him.

This is a disputed issue; Fishkin and others in support of admission say it’s perfectly legal for Garcia and others like him to work as independent contractors, even though it’s not legal to employ them as direct employees with tax withholding. Fishkin notes that Garcia is currently working as an independent contractor to stay within the law and shield his employer from criminal charges.

UCLA immigration law professor Hiroshi Motomura agrees that Garcia can legally be self-employed, but says employers can still get in trouble if they disguise an employment relationship with an independent contractor format.

“The law is clear that if you’re an independent contractor, that’s not covered by employer sanctions,” says Motomura, who signed on to an amicus brief supporting Garcia’s admission. “What’s controversial is what constitutes an independent contractor.”

A related question is protection of the public. Even if Garcia is admissible, is it misleading to issue him a law license because he is not fully employable?

The Justice Department brief says no, emphasizing that employability is a function of federal law and completely separate from attorney licensing, a matter exclusively handled by states. The California committee agrees, noting that California issues law licenses to nonimmigrant aliens without regard to their employability—though LeClerc shows that not every state does.

Fishkin notes that because attorney licensing is historically reserved to the states, it would be a major change for Congress to step in. That kind of pre-emption is done expressly, he argues, not impliedly.

Employability was the subject of close questioning in oral arguments in Godinez-Samperio’s case. The Florida justices expressed concern that even though Godinez-Samperio has restrictions on his employability, the public may believe he is fully employable if he is issued a law license.

Some of the justices seemed to believe this could be resolved if Godinez-Samperio is granted a work visa through the deferred action program. The issue may be resolved by a change of status for Garcia and Vargas as well. But for others not fortunate enough to obtain an adjustment of status, nothing but a bright-line ruling may end the debate.

A QUESTION OF BENEFIT

Godinez-Samperio’s case was started and largely briefed before Garcia’s. While that made Florida the first state in the nation to consider the issue, it also left out an issue that may be dispositive in California and other states: whether bar admission is a “public benefit” under the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which makes “unqualified aliens” ineligible for “any state or local public benefit.”

The Justice Department made a media splash when its opinion argued against admission solely on those grounds. It put the federal government in opposition to California attorney general Harris and the state Committee of Bar Examiners, among others.

The issue turns on whether a law license is a public benefit as the law defines it. The law says a state or local public benefit includes “any … professional license … provided by an agency of a state or local government or by appropriated funds of a state or local government.” Most parties agree that the California Supreme Court, which issues law licenses in California, is not an agency of the state but a co-equal branch of government. DeSha argues that federal definitions make the court an agency. (See “Is a Law License a Public Benefit?” at left.)

Underlying the admissions issues is the larger national debate on immigration. Many of the same arguments made in the political sphere cropped up in the Garcia and Godinez-Samperio cases, especially in amicus briefs.

Amici curiae supporting admission of Godinez-Samperio and Garcia frequently cite the 1982 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Plyler v. Doe, which said the 14th Amendment requires states to provide a public education to children brought into the country illegally.

The majority reasoned that such children bear no responsibility for their circumstances, and that failing to educate them would create an “underclass” with little education and high unemployment, likely creating social problems.

The same reasoning applies to bar admissions, argued the Mexican American Bar Association of Los Angeles County. In support of Garcia’s admission, the organization’s brief said denying professional licenses would create the same kind of subclass, creating hardship for applicants and foreclosing their chances of contributing to society.

Indeed, the association said, if the state pays to educate DREAM Act-eligible children but does not permit them to pursue careers as adults, “we would be denying our state and this country the returns on their investment.” (See the sidebar, “Should Public Policy Favor Inclusion When It Comes to Bar Admissions?”)

State supreme court cases move slowly, but 3Ls graduate every spring. According to Vargas, the DREAM Bar Association has students in all three years of law school, as well as recent graduates—and some are gearing up to apply for bar admission. Those cases may not be in California, Florida or New York—Vargas predicts that Maryland and Arizona may be next—but the decisions in the first three states may help the others come to their own conclusions.

“They’re waiting only because they are still students,” he says. “Next year, you’ll see a much larger group of people applying.”

Godinez-Samperio didn’t expect to create the nation’s first case when he applied for bar admission; he just wanted to become an immigration and human rights lawyer.

“Certainly I knew that I was going to have a lot of problems, but I always think to myself: I need to take one step at a time,” he says.

“First I need to worry about getting into law school, then worry about how to pay for it, then worry about the next semester.”

“I didn’t think I should worry about [bar admission] until the time came, and that’s how I took it.”

Sidebar

Is a Law License a Public Benefit?

The U.S. Department of Justice departs from others in the case of Sergio Garcia on the issue of whether a law license is “provided by appropriated funds” of California’s state government. The Justice Department argues that it is because the state supreme court receives appropriated funds, but the Committee of Bar Examiners notes that applicant license fees are the sole source of funding for licensing. “While the final act of issuing the order of admission is done by this court,” the committee’s brief says, the license itself is not provided by appropriated funds.

Garcia’s brief agrees, but also argues that if the appropriated-funds rule does apply, the law nonetheless does not apply in California because 8 U.S.C. § 1621 permits states to pass their own laws expressly allowing “public benefits” for “an alien who is not lawfully present.”

And California Business and Professions Code § 6060.6 is such a law, it argues, because it permits bar applicants to submit tax identification numbers if they are not eligible for Social Security numbers.

In Florida’s oral arguments, supreme court Justice Charles Canady appeared very interested in whether Section 1621 applied, questioning at length the applicant’s attorney, Talbot “Sandy” D’Alemberte, a former ABA president. Canady noted that the Florida Supreme Court uses appropriated funds—and because the Florida Board of Bar Examiners is an agency of the court, that may bring it under the auspices of Section 1621.

But because the issue wasn’t briefed, the court never had an opportunity to examine detailed arguments for or against applying Section 1621. Thus, the section’s applicability in Florida may get its best examination in the high court’s ruling. And because it’s a federal question, the precedents set in Florida and California could have a strong influence on any questions that arise about the admission of Cesar Vargas in New York.

Lorelei Laird is a freelance writer in Los Angeles.