The G-Man

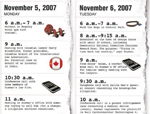

Click here (PDF) for a look

in Susman's daybook.

TO: ALLEN PUSEY, managing editor

FROM: TERRY CARTER, senior writer

SUBJECT: Story pitch on $1,000-an-hour lawyer

You asked me to look into doing a story on Houston litigator Stephen Susman as an example of the new breed of $1,000-an-hour lawyers.

It’s complicated. Seems he’s part of a breed all right. But it’s a breed of one.

Billables account for less than 20 percent of his work. He actually bills a bit more—$1,100. And he prefers making a lot more for himself by taking on some of the risk with other fee arrangements. The selling point is that clients will come out better, too.

On a random week we chose in November (see attached), Susman showed me that he billed 11.5 hours at that $1,100-an-hour rate of his, though he wouldn’t say what matter(s) or which client(s) were involved. But he seemed pretty surprised to discover when he looked a little deeper into his spreadsheets that in 2007, he had billed at hourly rates for a higher percentage of his time than usual.

The Susman Godfrey firm opened an outpost in New York City a little over a year ago. Nearly half the year he and his wife, Ellen, live in the Regency Hotel on tree-lined Park Avenue, just a block and a half from work.

Each morning Susman either works out for an hour or heads to nearby Central Park, where he walks his two Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, a toy breed that belies the nature of this particular owner.

And most mornings he has business breakfasts back at the Regency. (Mobil Travel Guide description: “Home of the original power breakfast, where deals are sealed and fortunes are made.”)

Since planting the Susman Godfrey flag in NYC a year earlier, Susman has been power-breakfasting, power-lunching and powering whatever else to get work from big New York law firms. He tells them he’s not out to steal clients. His firm has some specialties and some special ways of billing for them, and he pushes single-case litigations referred when firms are conflicted and such.

Says Susman: “I tell them we only do litigation for their clients as one-night stands, or like a heart surgeon. We’re not needed again.”

After the morning routine, he hoofs it to the office on Madison Ave. at 60th. The views from the newly built-out offices—the firm recently moved to double its space to 7,500 square feet—are OK, not spectacular. Unless you care that you’re next door to Calvin Klein’s flagship store and across from the upscale Barneys.

The offices themselves are nicely done, though without the effort some firms go to for an exalted aura of greatness. These folks are all about trying high-stakes commercial lawsuits.

Stephen Susman.

Courtesy of Stephen Susman

He’s a first-rate hustler.

Susman and his firm make for an amazing story: him the wild man, the counterintuitive business model, the high-stakes cases. There is no firm like it.

“I’m hustling New York City’s big firms,” says Susman. “And they’re listening.”

He is like a voracious animal, and that is the feeling you get in his presence. He scares people on his own side. The opposition is often terrified.

An associate in the firm’s New York office, Tibor Nagy, says Susman “is a force of nature.” I met some of the associates and partners, world-beaters on their own. They’re gorillas among lawyers. But when Susman walks by, it’s like they’re making way for Kong.

It seems like his id, ego and superego are all always on stage at the same time, such that he can bellow a pretty explicit expletive at a new acquaintance who pokes a little fun at him; somehow it works.

Susman’s evenings make you want to live in this city—with money. The night section of his daybook is to die for: the best of previews and openings for exhibits and shows, the best restaurants, etc.

His plane is parked in New York, though the two pilots are back in Houston till he needs them. He and Ellen were to leave at Thanksgiving for Houston and return to the Regency in March. (They prefer Texas taxes and spend more time there.)

S-G is as profitable as it is aggressive.

His now-90-lawyer firm is a litigation assault weapon, having made much of its reputation in antitrust and, more recently, thanks to the Eastern District of Texas becoming the plaintiffs patent-bar venue of choice, is big into IP litigation.

Revenues and profits per partner are off the charts, reportedly far and away the highest of all U.S. firms. Heavy emphasis on contingency fees and other alternative fee arrangements was a decade or two ahead of that emerging game.

His candlepower matches the physical presence. He left Houston for college at Yale in the early 1960s, then returned to the Lone Star State for law school at the University of Texas, where he is said to have had the highest GPA ever. Legend also holds him as the first clerk that Justice Hugo Black allowed to draft his opinions.

The firm hires almost exclusively former federal court clerks. All six who just came on board were: two of them at the U.S. Supreme Court and three at the circuits.

The business model probably is not replicable. They started in Houston in 1980 with an unheard-of plan: Do commercial litigation but make the money plaintiffs lawyers do in toxic torts, personal injury and medical malpractice. That meant alternative fee arrangements, especially contingency fees.

When $450 an hour was the top charged in a 1987 survey, Susman was getting $600 from the notorious Hunt brothers in Texas.

“At the beginning I wanted to hire lawyers who were personable and could persuade juries, young Joe Jamail types,” he says. In the one-lawyer, one-vote system that continues today, Susman lost. The firm wanted credentials: law review, top of class, federal clerkships. Quality attracts quality, they said.

Susman is flexible, and Bill Carmody proves it.

Susman was able to recall only one exception to the rule—an exception who now occupies the only corner office in the firm’s NY branch.

When Susman set up a shop in Dallas in the mid-’80s to represent the Hunts, a local lawyer named Bill Carmody sent him a letter inviting Susman and his wife to dinner.

“The letter seemed cold,” says Susman, and he didn’t respond. But Carmody kept at it, letter after letter. “I finally told my wife we might as well take the free meal at a good restaurant.”

They arrived early and were at the bar. Carmody, whom they’d never met, came in and clearly was known to the restaurant’s management. He’d done his homework: Susman’s favorite wines, and a version of the “Susman Tuna Tartare” then featured at the famous Tony’s Restaurant in Houston.

At that initial dinner Carmody, knowing where Susman went to college, asked if he’d be attending the Harvard-Yale game. Susman didn’t have tickets; Carmody could get them from a friend, former Dallas Cowboys running back Calvin Hill, himself a Yalie.

“I asked Bill whether he went to Harvard or Yale,” Susman says.

Neither. He’s from the Merchant Marine Academy.

“I like hustlers,” says Susman. “His law office in Dallas was the swankest I’d ever seen.”

So Carmody must have been quite successful already?

“No,” says Susman. “He was spending far beyond his success at that time.”

Susman wanted Carmody. But the firm blackballed him. Didn’t have the credentials.

Some years later, a couple of other prominent Susman Godfrey litigators worked a case with Carmody. They were convinced he’d make the grade, and Susman finally got his wish.

Carmody is now the No. 5 rainmaker this year in a firm that’s been averaging revenues of about $2 million per lawyer (including associates). In 2004, no partner took home less than a million bucks. In some years, associates have doubled their salaries with bonuses.

Carmody is near the top of the chart most dear to Susman: contingency work. This year his portfolio is 64 percent contingency, 32 percent fixed fee and 4 hourly. Partners get 40 percent to 60 percent of the premium from cases they bring in. Now it’s harder for Carmody to outspend his success.

Susman calls Carmody the firm’s concierge. “He can get reservations at the hottest places in New York, that day,” Susman says, ticking off the names of several prime locations.

Susman can throw a party.

The guest list from November’s first-anniversary party for the New York office had plenty of Who’s Whos. It was, says a guest from Cahill, the most amazing and impossible mix of defense and plaintiffs bar imaginable in NYC at one 250-person fete.

“Only Susman could pull this off,” the guest says.

It was catered to the max. By the Veuve Clicquot champagne stood bottles of Lone Star beer—an unexceptional brew, but a great label for the occasion.

There was Stanley Arkin of Arkin Kaplan, Bernie Nussbaum from Wachtell; and chatting for a long time by a table set with caviar and Russian vodka in Susman’s glass-front private office were Mel Weiss and Ted Wells.

(People noticed. Weiss has been indicted by the feds; and a former partner, Bill Lerach, had recently pleaded guilty. A prominent client of Wells, Scooter Libby, got off not long ago without serving a day in prison—albeit via commutation from the White House.)

The Houston firm has branched out over the years: Dallas, Los Angeles, Seattle and now New York. In each instance it has done so for what others would consider the wrong reason.

Law firms typically open new offices to follow clients or chase business. “We’ve done it when we’ve either wanted to get or keep a good lawyer,” says Susman.

Why now New York? The Big Apple was ripe for his hustle. And Susman wanted to be near his three grandchildren. Now 66, he wants to go another 10 or 15 years, if not more. The sheer élan in his approach to this new venture seems to have reversed the aging process.

Susman Godfrey looks for and holds on to entrepreneurial lawyers. The formal partnership track is four years, but no one stays that long without making partner. Everyone knows within two years or less whether mojo matches book smarts. Candid and pointed reviews at six-month intervals ensure it.

Each Wednesday all the firm’s lawyers, even if on the road, meet via conference call to consider three or four pitches to take on work. On Mondays, memos of 10 pages or fewer are circulated for each. About 20 percent are shot down. One that lost out this week was great on the law, precedent and other necessaries except for one thing: unclear on the money.

If all that doesn’t convince you …

He teaches environmental law on the side at the University of Houston. He has been working with the Inuits, who are losing their Arctic lands and lifestyles to global warming. He did pro bono work last year that stopped development of coal-burning power plants in Texas. He’s waiting for a federal circuit opinion that either will open or shut the door as to these being political or legal matters.

Though he is collecting piles of pelts and heaps of money in patent litigation—among major cases, he is countersuing IBM right now—Susman thinks business might slow down. On the day I was there, he had lunch with the CEO of Christie’s auction house, his classmate from Yale ’62. Susman says as the economy gets worse, people who commit to buying high-priced art back out—and need to be sued. He does that sort of thing.

Guests at the anniversary party included Peter Hewett, a director for a medical device manufacturing company that hired Susman for a patent battle in Texas. Hewett pushed aside his New York patent lawyers who worked up the case—he sees two of them across the room—and got Susman because he wanted a Texas lawyer litigating.

First there was mediation with William Sessions, former federal judge and former FBI director … and also a Texan. Susman was there with his client, Hewett. On the other side was a group of New York lawyers. They spoke first to “Judge Sessions.”

When they finished, Susman was brief: “Bill, we are out of here in 60 f—ing seconds if these guys can’t assure us that they can make decisions right now on behalf of their client.”

Liberal use of the f-word might be a verbal tick, or it might just speak to Susman’s directness in all matters.

Did I tell you this? Robert Rivera, who joined the firm in 1990 and recently made the move to New York, got the Houston office tour from Susman when he was hired.

A big, irregularly cut piece of cardboard was stuck to the wall in Susman’s office, and the new hire asked if it was a memento from Susman’s famous Corrugated Container antitrust case, in which he got one of the biggest dollar verdicts in history.

The quick explanation: “No, f—face, it’s a Rauschenberg.”

Some years later, Rivera had a chance to tell that story to the artist, Robert Rauschenberg, a Port Arthur, Texas, native. It prompted Rauschenberg himself to playfully jab at Rivera, saying Susman’s estimation had been pretty much on the mark.

But then Susman has made quite a mark as a litigator who doesn’t just eat what he kills—he consumes live prey in a most unconventional practice. He bills at $1,100 an hour but tries to avoid it so he can make a lot more.

Like I said, it’s complicated.

Correction

A firm represented by Stephen Susman, Sky Technologies, was incorrectly identified. The firm is based in Boston.The Journal regrets the error.