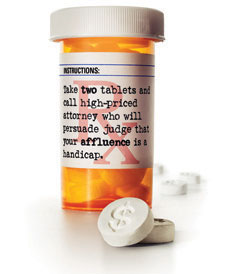

The privileged few walk away from trouble so easily, there's even a term for it

Illustration by Stephen Webster

“(______) has its rewards.”

How would you fill in the blank? Would you say virtue? Or patience? Or hard work?

How very “99 percent” of you.

These days, with the ever-widening gap between the 1 percent and the rest of us, that blank should more realistically be filled with the word affluence.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with affluence per se. Hard work should have its rewards. But when that affluence can serve as grounds for shedding all blame for one’s actions, it becomes time to examine where we’re headed as a society.

It’s probably safe to say that the average citizen is fed up with the rich and powerful misbehaving with little or no consequence. The Wall Street bigwigs who facilitated the 2008 worldwide financial meltdown went largely unscathed, and some say they’re up to their old tricks again. Teen heartthrob Justin Bieber continues to be charged with criminal conduct that would all but guarantee incarceration for a commoner, and it’s anyone’s guess as to why Lindsay Lohan still walks among us.

So what it seems to boil down to is that they’re either too big to fail or too rich to jail.

The latter appears to be true for a Fort Worth, Texas, teen who, while driving drunk a few blocks from his home, caused the deaths of four people last year. Ethan Couch, now 17, reportedly lived unsupervised in his own mansion—given to him after his parents’ divorce—before the deadly accident. His lavish lifestyle was said to consist of plenty of partying, including alcohol and drugs.

In juvenile court in December, Couch was sentenced to 10 years’ probation and rehab. His defense included testimony from Dr. G. Dick Miller, a psychologist who testified that, because of Couch’s privileged life and the poor parenting he received, he had been coddled and indulged and felt no sense of responsibility.

Miller used the term affluenza, coined by psychotherapist Jessie H. O’Neill in a 1997 book. It describes a nonmedical condition whereby the “afflicted” person feels immune from the consequences of his/her actions because of a privileged upbringing.

That term made the rounds again in April when it came to light that an heir to the DuPont chemical fortune had been convicted in 2009 of the sexual abuse of his 3-year-old daughter, but spared prison time. Greenville, Delaware, resident Robert H. Richards IV, who lives off a trust fund, had a high-powered defense team that argued that a wealthy man convicted of child molestation would not fare well in prison.

The judge reluctantly accepted the plea deal, saying that unlike most defendants in such cases, Richards had substantial family resources, so his eight-year sentence was suspended to probation and treatment. To further insulate Richards from any hint of trauma, he’s been allowed to remain at his 5,800-square-foot mansion.

These are but two examples of justice as it exists for the well-heeled. People of lesser means, knowing they would not likely be afforded the same consideration, might want to fill in a blank of their own: “In our justice system, (______) talks.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Richly Rewarded: The privileged few walk away from trouble so easily, there’s even a term for it.”