What’s the Matter with Kids Today

A group of test subjects ages 10 to 30 is asked to solve a puzzle. It involves rearranging a stack of colored balls on placeholders using as few moves as possible. Each wrong move requires extra moves to undo it.

The test is designed to measure impulse control. Adolescents tend to start moving balls almost immediately, which usually necessitates rearranging later. Adults, however, tend to take more time to consider their first move, which generally allows them to solve the puzzle on their first try.

In another experiment, designed to measure mature decision-making abilities, test subjects are presented with a choice between a small, immediate cash reward and a larger, long-term cash reward. Younger subjects invariably have a lower “tipping point”—the amount of money they are willing to take to get their reward immediately. Older subjects are more willing to wait.

A third experiment is designed to test the effects of peer pressure. Driving a computerized car simulator, subjects choose whether to run a series of traffic lights that are about to turn red, both alone and in the company of friends. Almost invariably, the younger subjects take greater risks when their friends are present; older subjects tend not to change their driving in either case.

This is the kind of research in developmental psychology and neuroscience that is helping to shed new light on differences between adolescent and adult brains. It’s also part of the science that lies at the heart of a series of decisions, including a May ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court in Graham v. Florida, that have changed the direction of juvenile justice.

Paolo Annino

Photo by Mika Fowler

Graham outlawed life-without-parole sentencing in nonhomicide cases for individuals under age 18, and it may be comparable to the Brown v. Board of Education case in juvenile justice, says Paolo Annino, a Florida State University law professor and director of the school’s children’s advocacy clinic.

It will likely lead to the resentencing of the estimated 129 juvenile offenders in this country now serving life sentences without possible parole for crimes in which no one was killed, give other juvenile offenders serving long prison sentences new grounds for seeking lesser sentences, and change our way of thinking about juvenile crime.

“It means we are finally acknowledging outside of the death penalty arena that kids are different from adults and need to be treated differently by the criminal justice system,” Annino says.

In Graham, the court held 5-4 that life without parole for a juvenile offender convicted of a crime not involving murder violates the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment. (Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. agreed only with the majority’s holding that Terrance Jamar Graham’s sentence was unconstitutional, not with its conclusion that all such sentences necessarily are.)

The majority based its decision in part on the scientific research into adolescent brain development first cited by the court five years ago in Roper v. Simmons, when it struck down the death penalty for juvenile offenders on the same grounds.

That evidence showed that adolescents, as a group, are more immature, more irresponsible, more susceptible to negative influences and outside pressures, and more capable of long-term change than are adults, which the court said made them categorically ineligible for the death penalty.

“These differences render suspect any conclusion that a juvenile falls among the worst offenders,” for whom the death penalty is reserved, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote for the 5-4 majority in Roper. “The susceptibility of juveniles to immature and irresponsible behavior means ‘their irresponsible conduct is not as morally reprehensible as that of an adult.’ ”

THE ROPER EFFECT

Roper marked a turning point for the court, which in 1989, in Stanford v. Kentucky, upheld death sentences for two child murderers: one a 16-year-old Missouri boy and the other a 17-year-old Kentucky youth.

It also spawned new Eighth Amendment-based challenges on behalf of three now-grown men doing hard time for crimes committed when they were juveniles. The first came from Christopher Pittman, a 21-year-old South Carolina man serving a 30-year sentence without possible parole for the murder of his grandparents in 2001, when he was 12. The court declined to hear it.

Next came challenges on behalf of Graham and another juvenile offender in Florida serving life sentences without parole for crimes in which no one was killed. Graham, now 23, was 16 when he received probation in the 2003 burglary and attempted robbery of a barbecue restaurant. In 2004, a month shy of his 18th birthday, he was involved in a home invasion robbery and was sentenced to life without parole.

Likewise, Joe Harris Sullivan, now 34, is doing life without parole for the rape of an elderly woman in 1989, when he was 13. At the time the court issued its decision in Graham, it dismissed Sullivan’s appeal as improvidently granted. The state had argued that Sullivan’s petition was procedurally barred because it wasn’t filed within the state’s two-year statute of limitations for appeals in noncapital cases.

Sullivan’s lead lawyer, Bryan Stevenson, executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala., says the Graham decision should give Sullivan and other similarly situated inmates new grounds to challenge their sentences.

Graham created a new categorical rule barring life sentences without parole for juvenile offenders convicted of nonhomicides, Stevenson reasons. And every time the court has created such a rule, it has been held to be retroactive.

“It’s an important win not only for kids who have been condemned to die in prison but for all children who need additional protection and recognition in the criminal justice system,” he says.

Justice Kennedy, who also wrote the majority opinion in Graham, said no recent data provided reason to reconsider the Roper decision and its observations about juveniles. If anything, he said, the evidence has become stronger and more conclusive in the five years since. Scientists say research demonstrates what every parent of a teenager probably knows instinctively: That even though adolescents may be capable of thinking like adults, they are mentally and emotionally still children.

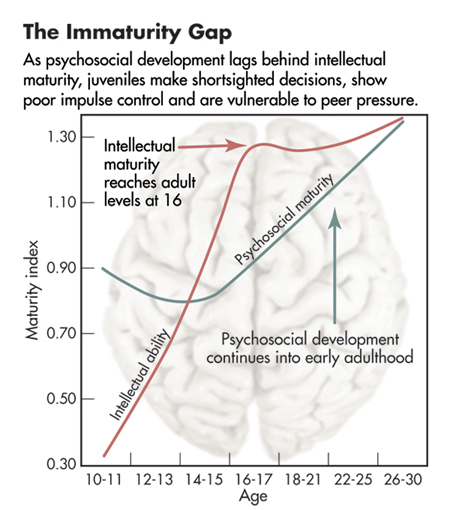

While an individual’s cognitive abilities (thinking, reasoning) reach adult levels around the age of 16, studies show that psychosocial capabilities (impulse control, judgment, future orientation and resistance to peer pressure) continue to develop well into early adulthood.

Which answers the question so many parents have undoubtedly asked their teenage sons and daughters: How could somebody so smart do something so dumb?

Laurence Steinberg

Photo by Alex Griesch

Laurence Steinberg, a Temple University psychology professor who has been studying adolescent brain and behavioral development for 35 years, likens the teenage brain to a car with a powerful gas pedal and weak brakes. While the gas pedal responsible for things like emotional arousal and susceptibility to peer pressure is fully developed, the brakes that permit long-term thinking and resistance to peer pressure need work.

Steinberg says the latest research in developmental psychology confirms and strengthens the conclusion that juveniles as a group differ from adults in the salient ways the court identified in Roper. And emerging research in the field of neuroscience, not even mentioned in Roper, is helping to explain this biologically.

NEURAL TIMEBOMBS

Such research shows, for instance, that adolescents exhibit more neural activity than adults or children in areas of the brain that promote risky and reward-based behavior. It also shows that the brain continues to mature well beyond adolescence in areas responsible for controlling thoughts, actions and emotions.

Steinberg, a leading researcher in the field, says he knows of no serious debate over the merits of the science. While there will always be those who say more research is needed, he says he knows of no studies contradicting all the neurological and behavioral research that shows the brain is still maturing during adolescence, and that the maturation process continues well into adulthood.

Steinberg, it should be noted, was not a disinterested party to the litigation. He served as the lead scientist on an amicus brief filed by the American Psychological Association and others in Roper and Graham. He also believes that juveniles, because of their developmental immaturity, should not be held to the same standards of criminal responsibility as adults. He’s far from alone.

More than a dozen legal, religious, correctional, human rights and child advocacy organizations filed amicus briefs in support of the petitioners, including the ABA, the Prison Fellowship Ministries, Amnesty International and the Juvenile Law Center. So did groups of former juvenile offenders, friends and family of juvenile crime victims, educators and members of the juvenile corrections community.

The American Medical Association and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry also filed an amicus brief in support of neither side. Though they took no formal position on the constitutionality of life-without-parole for juveniles, their brief summarized matter-of-factly the same scientific findings in briefs filed in support of the petitioners.

The ABA, for its part, argued that sentencing a juvenile offender to life without possible parole was irreconcilable with the court’s holding in Roper.

A group of former juvenile offenders who have since become productive, law-abiding adults, including former U.S. Sen. Alan Simpson of Wyoming, argued that it is “fundamentally inhumane” to give up on youthful offenders, as their own brushes with the law had shown. The brief said Simpson helped set fire to an abandoned building, fired a rifle at a road grader, and slugged a cop who tried to arrest him after a bar brawl.

The state, for its part, didn’t dispute the array of medical and social science research cited by the petitioners that juveniles are developmentally different from adults. It said the criminal justice system already takes such factors as age and the severity of the crime into account in many ways. And it said the state needed to retain the authority to mete out adult-style punishments to violent juvenile offenders who commit adult-like crimes.

“Extending the rationale of Roper, developed in the limited context of the death penalty, to the exceptionally broad and virtually unlimited context of prison incarceration is compelled neither by legal logic nor by societal norms,” the state said in its briefs. Though others filed briefs in support of the state—including the National District Attorneys Association, 19 state attorneys general, 16 members of Congress and a coalition of families of people killed by juvenile offenders—only one took issue with the validity of the scientific evidence put forth by the AMA and others.

That brief, filed by the Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, a public interest law firm based in Claremont, Calif., said evidence cited by those on the other side was far from being established as scientific fact.

Such evidence might be the type of “developing” science that lawmakers might want to consider when making policy choices, said the CCJ, but it is not the type of evidence that a court should ever use to overturn those policy decisions, and it has yet to meet federal admissibility standards. “The argument that the juvenile brain is too insufficiently developed to constitutionally permit imposition of life in prison without the possibility of parole (LWOP) for the most heinous and violent criminal offenses is predicated on advocacy masquerading as science,” the center said.

DEGREES OF DIFFICULTY

The National District Attorneys Association, on the other hand, argued in its brief against the imposition of a categorical ban on life without parole for juveniles. It said such a “one-size-fits-all” approach was not mandated by the Constitution and would also run afoul of the court’s holding that in noncapital cases the Eighth Amendment only prohibits sentences that are “grossly disproportionate” to the underlying crime.

Another brief on the state’s behalf by 19 other state attorneys general said life without parole for certain juvenile offenders is needed by states that must respond to ongoing violent juvenile crime.

“No one wants to believe that young people can commit horrible crimes. But sometimes they do. And no one wants to consider whether they should serve lengthy prison terms. But states must consider it, since they are responsible to their own citizens for protecting them, for deterring crime, for assuaging the victims, and for punishing the guilty,” it said.

A third brief on the state’s behalf by the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Lifers, a group representing the families of people murdered by juvenile offenders, cited what it said is an “overwhelming national consensus” in favor of a life-without-parole sentence for juvenile offenders who show an exceptional disregard for human life.

Graphic by C. McCabe

“Courts, legislatures and American people have strongly approved of these sentences as an effective and lawful device to deter juvenile crime and protect law-abiding citizens,” it said. “A criminal justice system which categorically denies constitutional and proper sentences for juvenile offenders perpetuates no justice at all.”

Still, the scientific evidence on adolescent brain development was central to arguments by both Graham and Sullivan.

Sullivan’s lawyers cited what they described as a “scientific consensus” on adolescent brain development as evidenced in Roper. “Roper understood and explained why such a judgment cannot rationally be passed on children below a certain age,” they wrote. “They are unfinished products, human works-in-progress. They stand at a peculiarly vulnerable moment in their lives. Their potential for growth and change is enormous. Almost all of them will outgrow criminal behavior, and it is practically impossible to detect the few who will not.”

Graham’s lawyers, on the other hand, contended that a life-without-parole sentence for a 16-year-old is unconstitutionally disproportionate to that for adults who have committed the same crimes.

“As the Roper court noted, juveniles are more malleable and capable of reform than adults: It is cruel to simply ‘give up’ on them,” their brief said.

Bryan S. Gowdy of Jacksonville, Fla., Graham’s lead lawyer, notes that of the seven amicus briefs that were filed on behalf of the state, “not a single one of them was signed by a scientist. All of the science is on our side.”

NATIONAL RATIONALE

Besides the scientific research on adolescent brain development, the majority cited what it said was evidence of a national consensus against life without parole for juveniles based on actual sentencing practices in the states that permit it.

In so doing, it relied on a 2009 study by Annino and on its own research. The Annino study found only 109 juvenile offenders serving life-without-parole sentences for nonhomicides nationwide, more than two-thirds of whom—or 77 inmates—are incarcerated in Florida. The majority found on its own another 20 juvenile nonhomicide offenders serving life-without-parole sentences, bringing the total nationwide to 129. How ever, the solicitor general later said six federal inmates should not be included in the total because their sentences were not based “solely on nonhomicide crime.”

That means that only 12 of the 39 jurisdictions nationwide that permit life without parole for juvenile nonhomicide offenders actually impose such sentences, the majority reasoned, and most of them do so only rarely.

The majority also cited the relative severity of a life sentence for a juvenile offender in comparison to an adult offender and questioned the penological purposes of such a sentence. It noted what it said was a global consensus against life sentences for juvenile offenders under any circumstances, citing a 2007 study that showed the U.S. was the only country in the world that imposes life-without-parole sentences on juvenile nonhomicide offenders.

“A state is not required to guarantee eventual freedom to a juvenile offender convicted of a nonhomicide crime,” Kennedy wrote for the majority, which included Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer and Sonia Soto mayor. “What the state must do, how- ever, is give defendants like Graham some meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.”

However, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a stinging dissent in which he was joined by Justice Antonin Scalia and in part by Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. Thomas accused the majority of substituting its judgment for that of lawmakers, judges and juries, the District of Columbia and 37 states.

Thomas also assailed the majority for what he said was its faulty logic, pointing out its apparent willingness to accept a life-without-parole sentence for a juvenile offender who kills but not for one who commits an especially heinous or grotesque crime in which nobody dies. He was referring to the case of Milagro Cunningham, a 17-year-old Florida youth serving life without parole for the beating and rape of an 8-year-old girl he left for dead under a pile of rocks, whose case Roberts had also mentioned in his argument against the adoption of a categorical rule barring such a sentence.

Thomas also took issue with the evidence on adolescent brain and behavioral development cited by the majority, saying that even if such generalizations from social science are relevant to constitutional rule-making, the majority had misstated the data on which it relies, which differentiates between adolescents for whom antisocial behavior is a fleeting symptom and those for whom it is a lifelong pattern.

Gowdy, Graham’s lead lawyer, says he couldn’t be more pleased with the decision, which he says not only creates a categorical rule barring life sentences without parole for juvenile offenders but also requires states to provide all juvenile offenders with some type of meaningful opportunity for redemption.

ABA President Carolyn B. Lamm applauded the ruling, which she says gives correctional authorities and the courts the opportunity to help juvenile offenders who can be reformed, while keeping those who can’t behind bars where they can do no more harm. But she notes that the decision does not address the issue of life without parole for juvenile offenders convicted of homicides, which the ABA also opposes.

Hopefully, she says, lawmakers in states that still provide for such sentences will be persuaded by the ruling—as well as by recent legislation in states like Texas, which last year did away with life-without-parole sentences for juvenile offenders—to abolish the practice altogether.

Marsha Levick, deputy director and chief counsel of the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia, which also filed an amicus brief on behalf of Graham and Sullivan, says Kennedy’s opinion—in its acknowledgment of the research suggesting that teenagers are less blameworthy than adults and have a greater capacity for change—goes even further than anyone might have anticipated.

“When Roper came down, it wasn’t exactly clear if the court had moved beyond the view that death is different under Eighth Amendment jurisprudence to the view that kids are different,” she says. “With this decision, it is now clear that it has.”

REJIGGERING THE SYSTEM

After the ruling, Florida Attorney General Bill McCollum issued a prepared statement noting that the decision doesn’t prohibit “stern” sentences for juveniles who commit violent crimes. He also said he fully expected that Graham would be resentenced to a “very long” term in prison.

But McCollum acknowledged that the ruling will have a significant impact on the state’s juvenile justice and corrections systems.

“I will work closely with the legislature to identify and implement solutions that can better protect Florida’s citizens, families and guests,” he said.

Because Roper was a death penalty case and the court has repeatedly emphasized that “death is different,” as it did again in Roper, the decision has had little practical effect on noncapital cases.

But when Roper is cited, it is usually cited by the defense in support of the proposition that juvenile offenders—due to their inherently diminished culpability—should not be subject to the same criminal sanctions as adults.

A lot of people, including Sullivan’s and Graham’s lawyers, found it ironic that California, which apparently has no qualms about locking up juvenile offenders for nonhomicide offenses for life (it currently has four), cited Roper in its appeal of a district court ruling that struck down a state law banning the sale or rental of violent video games to children long before the Graham decision came down. The court granted cert in Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association for next term.

In its petition, the state cites Roper’s recognition of the “constitutionally significant, fundamental differences” between adults and minors—in particular, its findings that juveniles “lack maturity” and are “more vulnerable or susceptible to negative influences and outside pressures”—as part of its justification for trying to keep violent video games out of the hands of children.

A federal judge in San Jose, Calif., found the law unconstitutional in 2005 on the grounds that it violated the First Amendment rights of the video game industry. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at San Francisco affirmed the decision last year.

State officials refused to comment on the pending appeal. But they referred a reporter to the brief they filed in the 9th Circuit, which doesn’t even mention Roper. It does, however, cite what it says is a “large and continuously developing” body of social science suggesting that children who play violent video games can become aggressive, engage in antisocial behavior and perform poorly in school.