5 women with extraordinary careers honored by Margaret Brent Awards

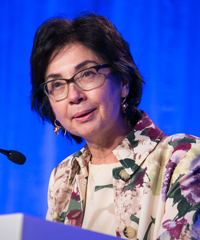

Prof. Emma Coleman Jordan received a Margaret Brent Women Lawyers of Achievement Award. All photos by ©Kathy Anderson.

Corrected: Women who have brought change to the legal profession by cutting paths that might ease the journey for those following can plot and plan all they want, but sometimes their achievements result not only from hard work and smarts but also how they respond to challenge and adversity. That theme came through the widely varied careers of the five winners at the Margaret Brent Women Lawyers of Achievement Awards luncheon on Sunday at the ABA Annual Meeting in Chicago.

The awards, named for the nation’s first female lawyer, Margaret Brent, honors women who have made their ways with distinction in a profession that, all these many years later, still hasn’t fully gotten used to them. But one thing is clear: These women, and others like them, continue moving things ahead and look back only to highlight what has been done and what still needs to be done.

The winners’ individual stories, presented in documentary videos and in person at the 25th annual awards luncheon, “are like the stones of our monuments,” Professor Emma Coleman Jordan, one award recipient, told the audience in a crowded hotel ballroom. Jordan’s speech stood out even among five unusually powerful ones because of her story and her storytelling prowess, jumping from stark descriptions of egregious discrimination to whooping humor that sears into memory the whole lesson.

She told of her parents fleeing the Jim Crow South of Louisiana in 1945 for a greater chance at a good life in Berkley, California, before she was born. They had to ride in the train’s “Jim Crow car,” directly behind the cinder-belching, coal-burning locomotive and packed with African-Americans with steamer trunks and baskets of fried chicken, she said. After a pause, she added, “Sounds like United Airlines, right?”

Jordan said she has given a number of speeches over the years when receiving awards but that now, for this one, it was time to go beyond generalizations about her experience and go on the record. Some of her stories came as punches in the gut, while others sparked laughter from the same spot.

“On April 6, my third wedding anniversary and second year at Howard, my 25-year-old husband died suddenly of a heart attack,” Jordan said. When she returned from his funeral in California, Jordan learned that some of the male students on law review had engineered a speech competition for selecting its editor-in-chief. Traditionally it went to the top graduate, and she’d led the class academically all the way and would graduate No. 1. “I spoke,” she said. “I won this election.”

Jordan’s visceral understanding of inequality formed her signature academic path in developing a legal theory of economic inequality and its effect on race, gender and sexual identity.

While the award winners have long lists of first in this or that endeavor, they don’t consider their achievements to be ends in themselves.

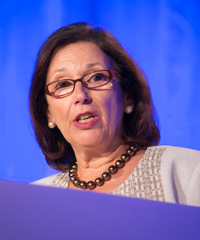

One recipient, Fernande R.V. “Nan” Duffly, went from being a refugee from an anti-Chinese political movement in Indonesia to a justice on Massachusetts’ highest court. She told the gathering that, “despite my personal success, our profession remains stubbornly immune to our individual and collective efforts to diversify it.”

The 2015 Margaret Brent Award winners are profiled below and their extended bios (PDF) have been made available by the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession.

AMBASSADOR MARI CARMEN APONTE

Ambassador Mari Carmen Aponte went to law school to become an advocate working for her community. Hailing from Puerto Rico, she had become a public school teacher in New Jersey, and in 1972 she got a message when minority students took control of the school and demanded greater educational opportunities. Skill in the law might help her better address the long-standing problems those students—and the community—faced.

Aponte went to Temple University School of Law under an affirmative-action program and became the first Latina lawyer in Pennsylvania. Her list of firsts, and accomplishments, grew longer. Eventually, Aponte became the U.S. ambassador to El Salvador through a recess appointment by President Barack Obama in 2010. Subsequently she was confirmed by the Senate in 2012 to continue there.

It was not her first work directly tied to Washington. In 1979, Aponte was named a White House fellow, working as an assistant to the secretary of Housing and Urban Development. She then co-founded a minority-owned firm in that city and in 1984 was elected the first female president of the Hispanic National Bar Association. Next, Aponte was appointed executive director of the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration, representing Puerto Rico’s government in matters concerning federal, state and local governments in the United States.

President Bill Clinton named Aponte a special assistant in the Office of Presidential Personnel, where she worked on appointments of Latinos. Later, Aponte would be one of a group leading the advocacy for Sonja Sotomayor’s appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. They’d become friends as young lawyers on the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund’s board of directors.

Besides navigating her own path to positions rarely, if at all, achieved by Latinas in the past, Aponte has worked every step of the way to help others do the same.

FLORA D. DARPINO

Coming out of law school, Flora D. Darpino made a tactical decision on how to follow her husband, who owed the U.S. Army four years of service as a lawyer in the Judge Advocate General Corps. She knew that as he changed assignments and they moved from place to place, she would have to be admitted to the bar in state after state, sometimes requiring more bar exams. So Darpino joined the Army JAG Corps, too.

She now is the Army’s top lawyer, as the Judge Advocate General, aka TJAG. Darpino was promoted to lieutenant general (three-star) when appointed to the position and is the first woman to head the Army’s legal arm since the job was created in 1775. Among other duties, she is principal legal adviser to the secretary of the Army.

Darpino had to navigate rough terrain on her first assignment in 1987. Her boss greeted her thusly: “I told them I didn’t want a woman, but they sent you anyway.” He eventually declared her his best young lawyer.

She was deployed twice in Iraq, first in 2002, early in the war, as senior lawyer for the 4th Infantry Division (Mechanized), as a kind of general counsel and district attorney. After being promoted to full colonel, Darpino returned to Iraq in 2010-2011 in the role of senior lawyer for all U.S. forces there as combat operations were winding down.

Darpino worked many roles as an Army lawyer—in courtrooms, administration and leadership positions. She was commander of the Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and school, the only ABA-accredited military law school with an LLM program. She was the JAG Corps’ chief recruiter and directed recruiting goals and policies; applications increased during her tenure.

Not that Darpino didn’t get a taste of the Army’s most basic mission. In 1995 she asked to be assigned to the legendary combat paratrooper outfit, the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault.) As a woman—a short one—she was not required to take the airborne air assault course, which is physically rigorous. But she insisted on earning her assault wings the old-fashioned way, and she did.

JUSTICE FERNANDE R.V. “NAN” DUFFLY

As a college student, Justice Fernande R.V. “Nan” Duffly worked in a legal assistant program and realized that lawyers can have a significant social impact. She had been born in Indonesia to a Chinese mother and Dutch father, and the family had to flee upheaval there when she was an infant, later ending up in the United States. Duffly had a keen sense of fairness and equality, and when she entered Harvard Law School in 1975, Duffly complained to an assistant dean about lack of women and people of color. And she offered a solution. Duffly got funding for a group she helped form that could go to various colleges to encourage women and minorities to apply to Harvard Law, and also a group of telephone mentors to help them once accepted.

Her efforts proved to be a lifelong theme. Her first job was at Warner and Stackpole, now K&L Gates, which was known for accepting female lawyers and emphasizing pro bono work. She became the first female litigation partner. She went on to be an associate justice on the Massachusetts Probate and Family Court Department in 1992, then in 2000 was appointed to be an associate justice on the Massachusetts Appeals Court. Duffly was appointed as the first Asian-American associate justice on the Supreme Judicial Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 2011.

She helped spearhead a change in the way law firms report certain statistics—they were taking credit for having female partners, but excluding many of them when reporting profits per partner. The concern was that women and minorities might be underrepresented in full-equity partnerships. As a result, NALP overhauled its data collection; and now most firms make that distinction.

As president of the National Association of Women Judges in 2007-08, Duffly worked with elected officials and policymakers to increase the number of women on the state and federal benches. She still works for opportunities and change for women who have come after her.

MARY ANN HYNES

It was a tough time for women entering the legal profession when Mary Ann Hynes graduated from law school in 1967. She took what sometimes could be an even tougher route: working inside big corporations. She went to work in 1971 as a legal editor at CCH, an information services company for tax, accounting, legal and business professionals. By 1979 she was the company’s general counsel, the first female general counsel of a Fortune 500 company. When it was acquired by Wolters Kluwer, she was named top legal officer and general counsel.

Hynes would be the first female officer at several multinational companies in her career. In 2013 she was named senior vice president and counsel to the chairman of Ingredion, formerly Corn Products International. She now is a senior counsel with Dentons U.S.

As chair of the membership committee of the Chicago Network, an invitation-only group of professional women, she led efforts to recruit other female general counsel. InsideCounsel magazine created the Mary Ann Hynes Pioneer Award for female general counsel who went from simply being the first in their positions to bringing change to open doors for others.

PROFESSOR EMMA COLEMAN JORDAN

Emma Coleman Jordan’s studies focused on banking, finance and the Uniform Commercial Code when few women did so, and she has expanded it to areas where no one had gone before. For example, Jordan is credited as the founding scholar of the legal theory of economic justice. Her textbook, Economic Justice: Race, Gender, Identity and Economics, entered its second edition in 2011. Jordan cut a new path in academia with her focus going beyond employment discrimination, aiming at inequality in general in matters of race, gender and sexual identity.

After graduating first in her class from the Howard University School of Law in 1973, Jordan became a Stanford Law School teaching fellow, then taught at the University of Santa Clara Law School before moving on to the University of California at Davis, where she gained tenure. In 1981 she was a White House fellow, as an assistant to the attorney general.

She has been tenured at the Georgetown University Law Center since 1987, where she began working on an interdisciplinary approach to economic inequality. She created the Georgetown Future Law Professors Fellowship as well as the Northeast Corridor Collective of Black Women Law Professors; both groups offer advice and support for young academics.

In 1991, Jordan was on a team of lawyers representing professor Anita Hill during the Clarence Thomas Supreme Court confirmation hearings. At the time, she was the first African-American president of the Association of American Law Schools. That work on the Thomas hearings helped provide the nation with a primer on sexual harassment. Later, Jordan and Hill collaborated in editing a book of essays, Gender and Power in America: The Legacy of the Hill-Thomas Hearings.

• See what people are saying about the events on social media, and follow along with our full coverage of the 2015 ABA Annual Meeting.

Updated Aug. 3 to include correct photographs of Emma Coleman Jordan.