What lessons can Americans draw in 2016 from the WWII-era internment of Japanese-Americans?

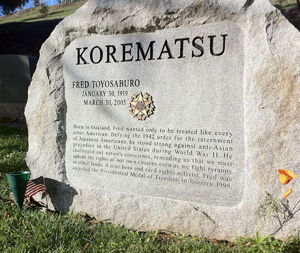

Photo of Fred Korematsu’s gravestone from Wikimedia Commons.

When Dale Minami was in law school, Fred Korematsu was a name on a casebook, a lesson about the power and the limits of the courts.

In the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1944 case Korematsu v. United States, the court ruled that Executive Order 9066, President Franklin Roosevelt’s order to round up and imprison Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast, was constitutional. In so ruling, it upheld Korematsu’s conviction for refusing to leave for one of the camps.

So in the early 1980s, Minami was surprised to get a call from researchers who had turned up papers showing that the federal government had withheld and altered evidence during Korematsu. Among other things, officials had recommended against imprisoning people on the basis of Japanese ancestry alone, saying they were not a threat. The researchers said Korematsu wanted to reopen his case based on this new evidence. He was joined by Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui, who had lost two Supreme Court challenges in 1943 to a curfew for Japanese-Americans.

“I [said], ‘Are those men still alive?’” recalled Minami.

They were still alive, and Minami was among the lawyers who helped them successfully nullify their convictions. That story was a major part of a Thursday afternoon discussion organized by the ABA’s Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice, “Getting It Right Next Time: Collective Judicial Response to Executive Order No. 9066.” Held as part of the ABA Annual Meeting in San Francisco, it was the final in a series of events the section held for its 50th anniversary.

Korematsu and the other men (whose cases were venued in Portland and Seattle, reflecting where they were during the 1940s) had petitioned for writs of coram nobis, a writ that permits the court to reopen a case if it discovers a factual error that could have changed the outcome. Korematsu’s case was assigned to U.S. District Judge Marilyn Hall Patel in San Francisco. Patel, now retired, said her initial reaction was that she didn’t have the power to overturn U.S. Supreme Court cases, as much as she’d like to.

But when she looked at the record, it was clear that the same misrepresentations made to the Supreme Court had been made to the district court. That was enough to give her jurisdiction. She granted the writ, nullifying Korematsu’s conviction. The other two men eventually won their cases as well. However, the Supreme Court’s Korematsu decision remains on the books, despite efforts by Minami and others, and a denouncement by former Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal.

Patel said imprisonment of Italian-Americans and German-Americans on the East Coast was not as widespread, and suggested that a major part of that was because they didn’t look quite so different as Japanese-Americans did.

“That was why I waxed a little eloquent at the end of that decision,” she said. “I felt it was important that we remember that.”

One lawyer who’s unlikely to forget it is Farhana Khera, executive director of Muslim Advocates in Oakland, California. Khera was asked to talk about whether something like the Japanese-American imprisonment could happen again, and her answer was yes. Speaking during a presidential election that has put American Muslims under a spotlight, she made express reference to Republican candidate Donald Trump, who has proposed banning all immigration of Muslims to the United States and having Muslims already here register.

Trump isn’t the only one with such ideas, she said; other politicians have said unkind things about Muslims or proposed limiting their civil rights. And this is trickling down, she said; she’s heard from parents of children as young as 6 who think they could be deported if Trump wins the presidency. From a legal standpoint, cases against people designated “enemy combatants” during the Bush administration have made it unclear whether American citizens can be detained or imprisoned without congressional approval, she said.

Nonetheless, Khera added, there has been good news as well. Muslim Advocates challenged surveillance of Muslims by the New York Police Department in New Jersey federal court and won a strongly worded decision from the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, rebuking the police for suspicionless surveillance and drawing an analogy to the internment of Japanese-Americans.

“It gave us a glimmer of hope,” she said. “There were several amicus briefs filed in that case, and the most moving was filed by Karen Korematsu,” Fred Korematsu’s daughter.

Follow along with our full coverage of the 2016 ABA Annual Meeting.