An estimated 10 percent of death row inmates are veterans, report says

Image from Shutterstock.

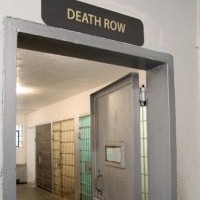

A report by the Death Penalty Information Center estimates there are at least 300 inmates on death row who are military veterans, a number that represents about 10 percent of the capital population.

Many death row veterans suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder or other mental disabilities related to combat, yet in many of their cases, their military service and related illnesses “were barely touched on” at trial, according to an executive summary by the center.

“Defense attorneys failed to investigate this critical area of mitigation; prosecutors dismissed, or even belittled, their claims of mental trauma from the war; judges discounted such evidence on appeal; and governors passed on their opportunity to bestow the country’s mercy,” the executive summary says.

The first person executed in 2015, Andrew Brannan, was a decorated combat veteran who suffered from PTSD after fighting in Vietnam, the Death Penalty Information Center says. He killed a police officer who stopped him for speeding. At his trial, the defense made little mention of Brannan’s military service and a prosecutor mocked his claim of PTSD, saying “everybody’s got a little bit of PTSD,” according to the center’s report (PDF).

The report bases its estimate of veterans on death row on a 2007 study and interviews with capital litigators in states with large numbers of capital inmates.

Though the overwhelming majority of veterans don’t commit violent crimes, veterans who are in prison are more likely to be there for homicide than those who didn’t serve in the military, the report says.

A New Yorker article sees a connection between the death row statistic and “the lost promise of military service.” The story notes that about 7 percent of the population have served in the military, a smaller proportion than the estimated 10 percent of veterans on death row.

“Earlier generations of veterans came home from war to ticker-tape parades, a generous G.I. Bill, and a growing economy that offered them a chance at upward mobility,” says the New Yorker article by Jeffrey Toobin. “Younger veterans returned to PTSD, a relatively stagnant economy, especially in rural and semi-rural areas, and an epidemic of drug abuse. And they came home to a society where widening income inequality suggested the futility of their engagement with the contemporary world.”

Edited at 11:23 a.m. for clarity.