Chemerinsky: Justice Gorsuch fulfills expectations from the right and the left

Erwin Chemerinsky. Photo by Jim Block.

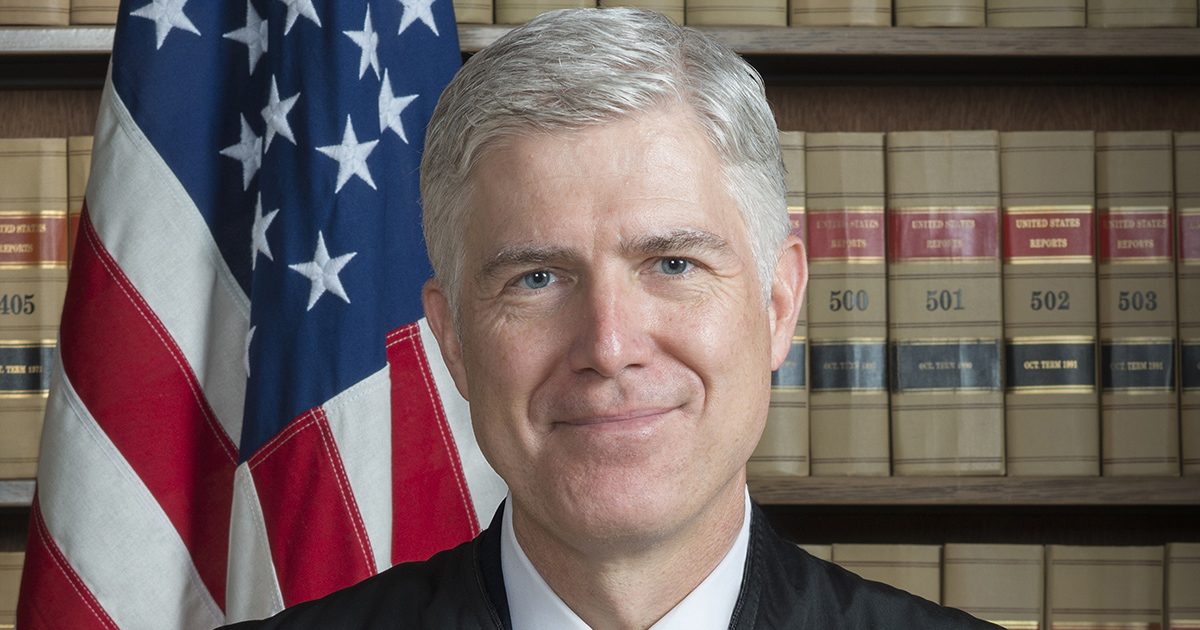

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil M. Gorsuch was sworn in April 10, 2017, so now he has been on the court for slightly over two terms. Overall, he is as conservative as those on the right had hoped, and those on the left had feared.

As expected, he has espoused a judicial philosophy like that of the justice he replaced, Antonin Scalia, stressing originalism in constitutional interpretation and plain meaning in statutory cases.

Gorsuch has consistently been with the conservatives in what are generally regarded as the most important 5-4 cases since he came on the court. This past term, for example, in Rucho v. Common Cause, he was with the other conservative justices in holding that challenges to partisan gerrymandering are nonjusticiable political questions.

He also was in dissent with Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Brett M. Kavanaugh in Department of Commerce v. New York, which held that the Trump administration failed to offer an adequate justification for wanting to put a question about citizenship on census forms.

A year ago, in his first full term on the court, Gorsuch was with the other conservative justices in upholding President Donald Trump’s travel ban (Trump v. Hawaii) and in overruling long-standing precedent that allowed states to require nonunion members pay the share of the dues that supports the collective bargaining activities of the union (Janus v. American Federation).

A particularly revealing opinion about Gorsuch’s judicial conservatism came in his first months on the court when he dissented from a ruling that protected gays and lesbians. Arkansas law prevented both partners in a same-sex marriage from having their names listed on a child’s birth certificate. The court, in Pavan v. Smith, in a per curium opinion, declared this unconstitutional. Gorsuch’s dissent, which was joined by Thomas and Alito, was clear that he disagreed with prior rulings that had protected a right of gays and lesbians to marry.

It is clear that in some areas, Gorsuch wants to go further to the right than his conservative colleagues. But there are also instances where he will join the liberal justices. Gorsuch is 51 years old. He likely will be on the court for decades to come. But his initial terms give an indication of his jurisprudence, which is overwhelmingly conservative.

The cases about religion

In all of the religion cases decided in his time on the court, Gorsuch has been among the most conservative justices. In American Legion v. American Humanist Association, in June 2019, Gorsuch was with the majority in rejecting a challenge to a 40-foot cross on public property. Gorsuch, though, took the position that no one has standing to challenge religious symbols on government property. Under his view, any religious symbol displayed anywhere is permissible because no one is sufficiently injured to have standing to challenge it.

In Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018), Gorsuch and Thomas concurred in the judgment and said that it would violate freedom of speech as impermissible compelled speech to force a baker to design and bake a cake for a same-sex couple.

If ever this attracted support of the court’s majority, it would create an exception to virtually all civil rights law as all require the provision of services. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia Inc. v. Comer, during Gorsuch’s first term, he again joined with Thomas concurring in the judgment and urged the court to go much further in requiring the government to provide aid to religious institutions when it does so for secular private ones.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.’s majority opinion distinguished Locke v. Davey, which upheld a state refusing to allow its scholarship program to be used to support an individual’s study for the ministry. But Gorsuch and Thomas urged reconsideration of the case and made clear that they would overrule it.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil M. Gorsuch.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil M. Gorsuch.

The administrative state

As a judge on the Denver-based 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Gorsuch criticized the doctrine of Chevron deference, the principle of judicial deference to administrative agencies when they interpret the statutes they operate under. Many predict that he will be a leader on the court in urging greater judicial oversight over the administrative state. His opinions so far suggest that indeed he will try to push the court in this direction.

In Gundy v. United States (2019), the court rejected the argument that the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act is an unconstitutional excessive delegation of power by Congress to the executive branch of government. SORNA makes it a federal crime for a convicted sex offender to cross state lines if he or she has not registered as required by the law.

The statute left many matters to be resolved by the attorney general. Justice Elena Kagan, writing for the plurality, upheld the statute and deemed it an “easy” case for constitutionality. Gorsuch wrote a strong dissent, joined by Roberts and Thomas, and accused the majority of “working from an understanding of the Constitution at war with its text and history … and reimagin[ing] the terms of the statute before us.” He urged the court to revive enforcing the nondelegation doctrine, something the court has not used to strike down a federal law since 1935.

In Kisor v. Wilkie (2019), the court considered whether to overrule earlier cases, such as Auer v. Robbins (1997), which held that federal courts should defer to federal agencies when they interpret their own regulations. The court, in what was effectively a 5-4 decision, did not overrule Auer deference. Gorsuch wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment, but made clear that he would overrule this doctrine of administrative law.

He wrote: “It should have been easy for the court to say goodbye to Auer v. Robbins. In disputes involving the relationship between the government and the people, Auer requires judges to accept an executive agency’s interpretation of its own regulations even when that interpretation doesn’t represent the best and fairest reading. This rule creates a ‘systematic judicial bias in favor of the federal government, the most powerful of parties, and against everyone else.’ A legion of academics, lower court judges, and members of this court—even Auer’s author—has called on us to abandon Auer. Yet today a bare majority flinches, and Auer lives on.”

Following Scalia and Joining with Liberals

Yet it also must be noted that in the October 2018 term, in four 5-4 decisions, Gorsuch voted with the liberal Justices—Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Kagan—to create the majority. In two of these areas, Gorsuch was voting in the same way that Scalia likely would have decided. In June 2015, in Johnson v. United States, Scalia wrote the opinion for the court striking down the residual clause of the federal Armed Career Criminal Act as being unconstitutionally vague. This provision applied to those whose “conduct … presents a serious potential risk of physical injury to another.”

This term, Gorsuch wrote the opinion for the court in United States v. Davis, striking down on vagueness grounds the residual clause of a federal statute that provided for an enhanced sentence for using, carrying or possessing a firearm in committing a crime of violence. The residual clause in 18 U.S.C. §924(c)(3)(B) defines a “crime of violence” as a felony “that by its nature, involves a substantial risk that physical force against the person or property of another may be used in the course of committing the offense.” The court, 5-4, with Gorsuch joined by the liberal justices struck it down as unconstitutionally vague.

This should not have been a surprise. The term before in Sessions v. Dimaya, Gorsuch joined a majority opinion by Kagan, in a 5-4 decision, striking down a provision of a federal immigration statute that used language like the residual clause in Johnson.

Also, in United States v. Haymond (2019), Gorsuch wrote the plurality opinion in a 5-4 decision holding that a judge’s revocation of supervised release violated the Sixth Amendment. Andre Haymond had been convicted of violating federal child pornography law. He was sentenced to 38 months in prison to be followed by 10 years of supervised release. After Haymond’s release from prison, a judge found by a preponderance of the evidence that Haymond violated the terms of his supervised release and he was sentenced to five more years in prison.

Gorsuch, joined by Ginsburg, Sotomayor and Kagan, found that this violated the Sixth Amendment and, that under precedents such as Apprendi v. New Jersey (2000), the deprivation of liberty required proof beyond a reasonable doubt and the opportunity for trial by jury.

Both Gorsuch’s plurality opinion and Breyer’s opinion concurring in the judgment emphasized that the decision was just about revocation of supervised release under this statute. The key question for the future is whether it is possible to distinguish this federal statute from others providing for supervised release. Here, too, Gorsuch was following in the footsteps of Scalia who had been in the majority in Apprendi and the cases following it.