More law schools are covering bar review costs: Is it improving pass rates?

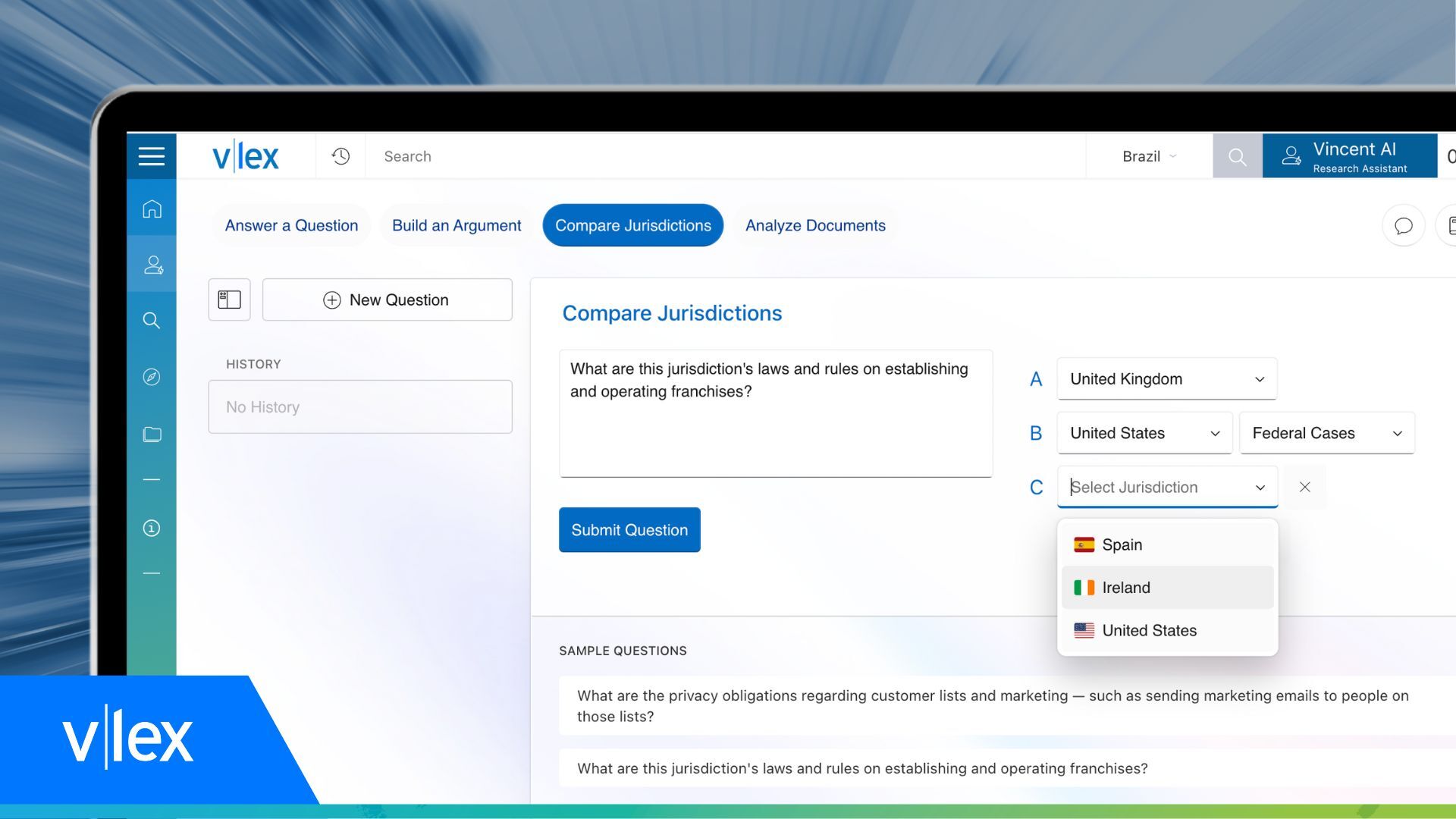

Out of law schools who have July 2016 bar results for first-time test takers, many saw their pass rate percentages drop.

And of the schools that saw pass rates rise, some are increasingly covering partial or entire bar review costs for graduates.

Mike Sims, president of the test prep group BARBRI Bar Review, told that ABA Journal that more than 30 law schools now pay for their students’ bar review. According to the business’s website, courses cost between $2,595 and $3,995, depending on when someone enrolls.

“I beg for money from alumni and say it’s a great investment, because otherwise these people will keep failing,” says Lawrence W. Moore, interim dean of Loyola University New Orleans College of Law.

The school’s first-time test-taker pass rate for July 2016 was 76.69 percent; last year it was 71.53 percent.

Depending on how many donations Loyola receives, the school attempts to pay for bar review courses and books for first- and second-time test takers. They don’t cover costs for alums taking the bar for the third time, but the school has a negotiated a reduced bar review rate for them.

Southern University Law Center, which is in Baton Rouge, has a first-time test-taker pass rate of 60.38 percent for the July 2016 Louisiana bar. Last year, their July first-time test-taker pass rate was 51.85 percent. The school offers graduates a free supplemental bar review course, focused on answering essay questions, and it negotiated a reduced rate for students with with private bar review groups. It also offers some students financial assistance to help defray bar review costs.

The law school is associated with a historically black college and has many nontraditional students who are the first people in their families to graduate from college, says Shawn Vance, a Southern law professor who teaches the supplemental bar review course. Sometimes students have problems paying for private bar review, he adds, as well as taking time off work to study for the exam.

You can take out extra law school loans to cover bar review, Vance says, but that requires some planning. After a student graduates, his or her credit is evaluated by traditional terms, and some recent graduates “are maxed out and don’t have any credit.”

“All of my students I believe have the capacity and the ability to pass the bar. The difficulty they are faced with is managing things that nontraditional students have to do to put themselves in the best position to succeed,” Vance says. “Once you give them the tools that they need, they do wonderful things in the law.”

Southern has ABA accreditation, and its chancellor, John Pierre, is concerned about a proposed accreditation standard change that would require that 75 percent of graduating classes pass a bar exam within two years. The ABA Accreditation Standards Review Committee approved the proposal in September and forwarded it to the governing council of the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, which is expected to consider it this week.

Under the existing standard, there are various ways a law school can be in compliance. One way is that at least 75 percent of graduates from the five most recent calendar years have passed a bar exam, or there’s a 75 percent pass rate for at least three of those five years. Also, a school can be in compliance if just 70 percent of its graduates pass the bar at a rate within 15 percentage points of the average first-time bar pass rate for ABA-approved law school graduates in the same jurisdiction for three out the five most recently completed calendar years.

Pierre and five other deans at law schools associated with historically black colleges and universities sent Barry Currier, the ABA’s managing director of accreditation and legal education, a letter in June, expressing concern about the proposal.

“If the ABA accreditation proposal becomes final, it’s going to affect the ability of schools to take chances on students from diverse backgrounds,” Pierre says. “We have found that for our students, it may take multiple times to take the bar exam and pass beyond that two-year period.”

Cutting the time period from five years to two years “is the more appropriate measure of whether a school is operating a sound program of legal education,” Greg Murphy, chair of the Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar, recently wrote in a memo (PDF) to Pam Lysaght, the Standards Review Committee chair.

According to Pierre, 90 percent of the school’s alums “eventually” pass the Louisiana bar exam. When asked if a law degree, without the ability to practice law, is in fact useful to people, Pierre said yes, and mentioned JD-preferred job opportunities in business, banking, sports and government. “That law degree has value beyond just passing the bar. More of our alums are looking at nontraditional [jobs] where their license is not what’s important. It’s their education that’s important,” he added.

Southern’s annual law school tuition for full-time students who are Louisiana residents is $13,560. Out of 194 students for the class of 2015, 70 had full-time, long-term jobs that required a JD, and 34 had full-time, long-term jobs that preferred candidates have a JD, according to its ABA employment summary (PDF). Thirty-one graduates had full-time, long-term professional positions that did not require or prefer a JD.

At Loyola University New Orleans, full-time tuition is $21,000 a semester. Out of 200 graduates in the class of 2015, 94 had full-time, long-term jobs that required a JD, and 11 had full-time, long-term positions that preferred candidates have a JD, according to its ABA employment summary (PDF). Twelve had full-time, long-term professional positions that did not require or prefer a JD.