Seeking justice in the killing fields

Associated Press

Even as Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital city, hurtles into the future, it can’t quite escape the past. At rush hour, the city’s tree-lined boulevards are clogged with Range Rovers and rusted bicycles alike. But not even the noise of Phnom Penh’s madcap traffic can compete with the sound of construction. One by one, high-rise buildings are going up, creating a skyline that looms over former French colonial villas and the shiny spires of Buddhist pagodas. Here is a city on the move, eager to join the ranks of Bangkok, Saigon—perhaps even Singapore. It doesn’t seem to have the time or the inclination to disturb the scars of the past.

But the scars are there, just below the surface. Strike up a conversation with a Cambodian in a cafe or start talking with the driver of your motorcycle taxi, and before long you’re likely to be casually told a story of such sadness and horror that it stings.

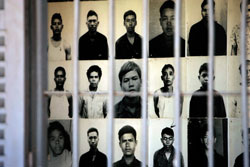

Or visit the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, on the grounds of one of the most notorious—and deadly—detention centers operated by the Khmer Rouge regime during its reign of terror from 1975 to 1979. The sun-bleached posters on the second floor of the museum are in shambles. The faces of surviving members of the regime’s leadership stare out from under layers of graffiti. In some of the posters, the eyes are scratched out; in others, the entire head is obliterated. Scrawled across all of them, in Khmer and English, French and Chinese, are comments of searing bitterness.

Click here to read the rest of “Seeking justice in the killing fields” from the March issue of the ABA Journal.