The Last Word: When the Last Thing You Want to Do Is the First Thing You Ought to Do

Illustration by Brad Yeo

It’s a case that stands out in the memory of Robert B. Fitzpatrick, an employment attorney in Washington, D.C., because of the intense emotions involved and because of the way it ended on a positive note for both parties.

A client who had worked for a local law firm for nearly 30 years was devastated by having been summarily discharged. Fitzpatrick invited three partners from the firm to his office to listen to what his client had to say and respond to her.

“I knew these folks and there was mutual respect,” he says. “I was able to say, ‘Guys, this is not a confrontational call. I think it would be useful if you came over and just let my client talk and tell her story.’ ”

They agreed and the client spoke at length with tears streaming down her cheeks. She had obviously been deeply wounded by the manner in which she was terminated. Fitzpatrick says the partners were touched by the hurt that had been visited upon his client. “They listened and they saw her weeping—not crying, just weeping uncontrollably. They got up and hugged her and said, ‘We are so, so sorry.’ ”

Within days, the entire matter was satisfactorily settled. Fitzpatrick says the fact that the encounter was entirely genuine contributed greatly to the outcome. “Nobody sat there and said, ‘OK now, this is a 408 settlement conference, so what we’re about to say to her is not discoverable or admissible, and it’s not an admission of fault. Sign here before we apologize.’ It just didn’t happen that way,” he says. “It was completely, totally sincere. And she went away no longer bitter. In terms of her emotional and physical health, that was a huge plus. It closed the chapter and she didn’t go away with a festering sore.”

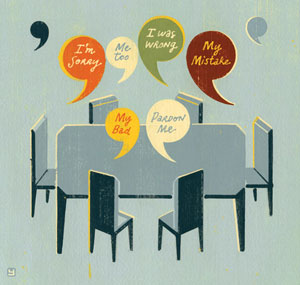

Few phrases in English or any other language have as much power to turn a tense or volatile situation into one ready for resolution as a simple “I’m sorry.” That’s been the case since the advent of language itself. Yet, often it’s the last thing a party is willing to say. In the legal profession, where an expression of remorse might be considered a tacit admission of liability, hardball tactics can result in major-league paydays, but at what price? If success is measured by how much the opponent has been bloodied, some say it might be time to use a different yardstick.

The “apology movement” has lately begun to gain real traction with lawyers who have come to realize that a contentious victory is often a hollow one. They know that finding joy and satisfaction in the legal life is at least as important as whether the case was “won.”

And while there are no hard-and-fast statistics to prove it, practitioners who have seen the toll taken by refusal to make peace on a personal level know that a satisfactory result in the legal matter will be difficult to achieve. Divorcing spouses who are perpetually at war, for instance, will part ways eventually with their property divided and child custody determined, but if the underlying hurts and resentments have not been addressed, the relationship will forever be uneasy. Lawyers of all types know that hard feelings get in the way of favorable outcomes, whether it’s between opposing clients, opposing attorneys or attorneys and their clients. And increasingly they’re realizing that they need to rejigger the status quo.

Is this indicative of a sort of clarion call to civility in the practice of law? It depends on whom you ask, though nary a lawyer is likely to tell you that would be a bad thing. But the question remains as to whether an apology is considered something to be used in the furtherance of common decency in the profession or whether it can be co-opted as part of a business strategy intended to mitigate potential damages. Lawyers who’ve been there know that the answer is both.

Click here to read the rest of “The Last Word” from the January issue of the ABA Journal.