With law firms lagging in diversity, how can GCs be a force for change?

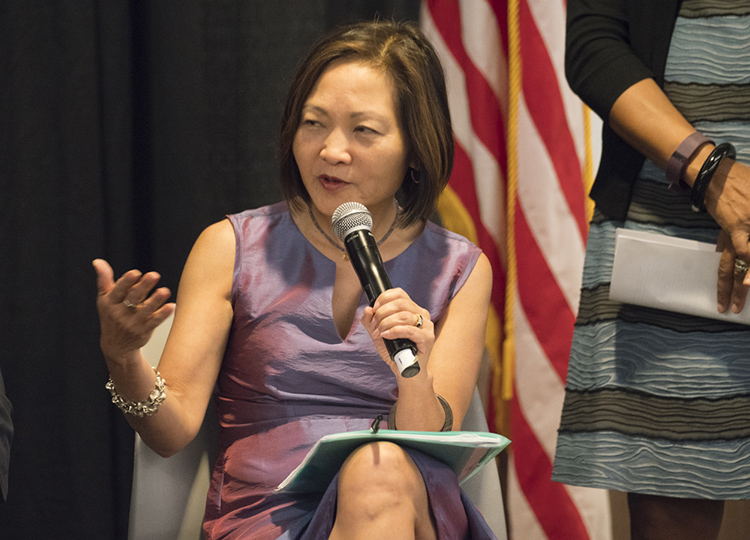

Vivia Chen of the American Lawyer’s Careerist blog. Photos by Len Irish.

Updated: Despite decades of lip service to the importance of diversity in the legal community, the upper ranks of most law firms still fail to accurately reflect the gender and ethnic makeup of practitioners or the population at large.

What accounts for this lack of progress, and what methods can be used to change it?

This was the issue at hand for the panelists at “The Business Case for Diversity: Is It Still Viable?” hosted by the ABA Journal and Working Mother Media on Friday at the ABA Annual Meeting in New York City.

Composed of partners at major law firms, general counsel for large corporations and journalists who have studied the issue of diversity in the legal profession, the panel was in general agreement that law firms lag behind the corporate world in improving diversity. They also agreed that without pressure from their clients—and consequences for failing to increase diversity in their upper levels—law firms are unlikely to change at the pace needed. But there was some disagreement on who owned the majority of the responsibility to effect the needed changes.

Panelist Vivia Chen of The American Lawyer’s Careerist blog says she felt part of the issue was a flawed premise that everyone is on the same page regarding the importance of diversity. Chen says that for the past 20 years, she’s heard that clients are pressuring firms to provide legal teams that are not just white and male, but she is not persuaded that is actually happening.

Chen cited figures from a recent trend report by the Association of Corporate Counsel which found that out of more than 1,800 in-house lawyers surveyed, only 6 percent reported that their departments collect data on the diversity of the law firms they hired, and only 3 percent say that they tracked how many women hold management positions in the firms they hired.

“If that’s the case, where’s the pressure?” Chen asked.

From left, Heidi Levine of Sidley Austin, Jeff Smith from Comcast Cable and Lynn Charytan from Comcast Cable.

Jeff Smith, deputy general counsel and senior vice president at Comcast Cable, says he has seen a shift in the way in-house counsel approach diversity in the firms they hire. In the past, he says, the standard line was one of neutrality, in which the companies would tell the firms that they did not care who represented them, just that they be qualified. Although the intention was to signal that the companies would be open to being represented by women and minorities instead of exclusively white men, this was not forceful enough to move the needle.

Lynn R. Charytan, executive vice president and general counsel at Comcast Cable, agreed with her colleague and says that in-house counsel must be willing to be more direct and demanding.

“I have called law firms and say: ‘Look at who you’re bringing me—surely you can find me diverse lawyers or women lawyers or both!’” Charytan said. “When I ask, they bring me that team.”

Charytan acknowledged the conversation can be difficult, but said if a firm is not providing diverse representation, then they deserve to be made “incredibly and exquisitely uncomfortable.”

Rick Palmore, senior counsel at Dentons.

Rick Palmore, who is senior counsel at Dentons and has previously served as general counsel at Sara Lee Corp. and General Motors, says he has seen increasing momentum at corporations to speak up and demand to see diversity in the legal teams that serve them. “The hue and cry is getting much greater, but the question is, what are the consequences?” he said.

Palmore says many firms had “a script of platitudes” when he asked about diversity in their firms, but that he was met with blank looks when he asked how the firms tracked their data.

With human resources departments being much larger and more influential at corporations than at law firms, diversity efforts have been easier to put into place in the corporate world, the panel said. It’s often hard to determine who at law firms should have the responsibility to gather diversity data, and diversity officers are often overwhelmed by their other duties, like providing advancement opportunities and mentoring support to young associates. But it is still necessary.

“You have to track the data,” agreed Hilary Preston, a partner at Vinson & Elkins. Preston says that the idea of data collection often provokes pushback and a fear of quotas being imposed on hiring. But it’s absolutely vital to evaluating how a firm is doing—not only at the entry level but also in the upper ranks of the firm.

Hilary Preston, partner at Vinson & Elkins.

One option for in-house counsel is to start factoring in a firm’s diversity during the pitch process, says Heidi Levine, a partner at Sidley Austin. She brought up a corporation that made 10 percent of each firm’s evaluation dependent on the firm’s diversity levels, so that it would be weighed along with cost and other factors. When firms are battling for business, tiny fractions can make a real difference, she says.

“Don’t underestimate the power of taking work away from firms,” Smith said.

On the flip side, the panelists agreed that when firms were doing a good job of providing diverse legal teams for their clients, positive reinforcement should be used via praise passed on to the upper management at firms.

In closing, Palmore said that when the task of achieving parity for minority groups and women seems overwhelming, he is reminded of the song “I’m Not Tired Yet,” by the Mississippi Mass Choir.

“We can’t afford to be tired,” he said. “We haven’t solved the problem yet.”

Follow along with our full coverage of the 2017 ABA Annual Meeting.

Updated at 11:05 a.m. on Sept. 1 to correct misspelling in first paragraph.