Trial between Oberlin College and a local bakery tackles First Amendment questions

Bosworth Hall on the campus of Oberlin College in Ohio. Photo from Oberlin College.

On the Friday after Donald Trump’s 2016 election win, Oberlin College’s administration sent an email to students and faculty addressing anticipated reactions to the victory.

The email, signed by Oberlin President Marvin Krislov and Meredith Raimondo, the college’s vice president and dean of students, acknowledged “fears and concerns that many are feeling in response to the outcome of the presidential election.”

Trump’s win was not the sole focus of the email, however. On the day after the election, three African American students from Oberlin College were arrested in connection with attempting to steal bottles of wine from a convenience store on the town square. After a brief scuffle with the shopkeeper, they were arrested and charged.

The school’s email additionally included the concern about the arrest incident: “We are deeply troubled because we have heard from students that there is more to the story than what has been generally reported. We will commit every resource to determining the full and true narrative, including exploring whether this is a pattern and not an isolated incident.”

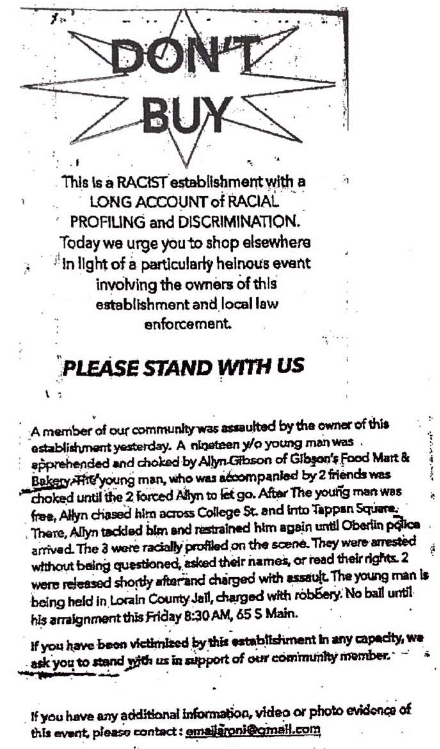

Some students at the small, liberal arts college in Oberlin, Ohio, instantly determined that the arrest was racist. They began protesting that the store, Gibson’s Food Market and Bakery, was a “racist establishment” and had a “long account of racial profiling”—accusations printed on a flyer handed out in front of the food market. The flyer also encouraged boycotting the store.

The protest against Gibson’s, a century-old, family business, eventually sparked a lawsuit that is scheduled to go to trial with jury selection beginning next week in the county seat of Elyria, Ohio, 10 miles from Oberlin. Gibson’s is suing the college for libel and slander, among other “actual malice” accusations, claiming in its civil lawsuit that the school’s defamatory statements caused long-term harm to the store’s name and business.

The lawsuit alleges that Raimondo was one of the people passing out the flyers and leading the demonstration using a megaphone, and that flyers were hung in college halls encouraging students and faculty to take their patronage elsewhere. Similarly, the lawsuit alleges that students used college resources to plan and execute the protest.

“This is a very interesting case because it has so many dimensions to it,” says Erica Goldberg, a law professor at the University of Dayton and author of the recent Columbia Law Review paper “Free Speech Consequentialism.” Goldberg says the case reflects “the debate over what the purpose of a university is, to be advocating discussion for all sides of a debate or advocating just for one.”

“It has the cultural flashpoints and polarization of the university free speech issue, which has gotten so much attention lately,” Goldberg adds. “It is extremely legally complex in tort law, in some ways, but has real, basic First Amendment issues to it as well.”

RACIAL TENSIONS AT OBERLIN

Racial issues have been at the forefront in recent years at Oberlin College, where about 5% of student enrollment is African American. In 2016, members of the school’s Black Student Union released a 14-page list of demands, referenced in the plaintiffs’ suit, based on the fact they thought the school was “an unethical institution.” In response, Krislov, the college’s president, said the school would “not respond directly to any document that explicitly rejects the notion of collaborative engagement.”

Tensions at Gibson’s came on the heels of another racially charged controversy at Oberlin: The school’s board of trustees fired rhetoric and composition professor Joy Karega, the only black female faculty member in the department, in November 2016 for posting allegedly anti-Semitic messages on social media several months prior. She sued the college for breach of contract and employment discrimination on the basis of race and gender. Demanding Karega’s guaranteed tenure was among the students’ varied demands to the administration earlier that year.

The Gibson’s lawsuit was filed after final charges were handed to the students. In August 2017, the three charged with shoplifting pleaded guilty to amended misdemeanor charges in county Common Pleas Court. The deal called for them to receive no jail time and to pay restitution. Included in the deal was a statement by the three students that Gibson’s employee Allyn Gibson was within his right to detain one of the students and that his actions were not racially motivated.

Disputes between businesses and big local educational institutions generally get settled without court filings, especially in places like Oberlin, with its small population of about 8,200 and even smaller college student body of about 3,000.

The college town needs the university community, and vice versa. But the balance here is under question. In fact, the school temporarily severed its partnership with the Gibson’s business because of the disputes; the business relationship has again been severed because of the lawsuit. “As this is now a legal matter, the College will suspend, effective immediately, its business relationships with Gibson’s Bakery until such time as a mutually productive relationship may be re-established,” the school said in an official statement.

THE LEGAL ISSUES

The Oberlin libel case comes down to some basic legal questions, according to Eugene Volokh, a UCLA law professor and free speech law expert.

The court has to determine whether the college’s participation in the protest might constitute aiding and abetting in libeling of the business, Volokh says.

“The tort law in play here means the plaintiff has to prove the school was going beyond just overseeing a student protest, but actively participating with a motive to defame the business. That’s not easy to prove,” he adds.

The school responded to the court case in its filing that Gibson’s “seek[s] to personally profit from a polarizing event that negatively impacted Oberlin College, its students and the Oberlin community.”

The college’s initial motion of dismissal also said the lawsuit falsely portrays Gibson’s as an innocent victim, but, “In reality, it was an employee of Gibson’s Bakery … who left the safety of his business to violently physically assault an unarmed student [just outside the store].” Oberlin also defended its administration’s presence at the protest because the school was concerned with the safety of its students and being there was part of its policy.

An image of the protest flyer was included in Gibson’s Food Market and Bakery’s libel and slander lawsuit against Oberlin College.

In a pretrial ruling, Judge John Miraldi denied the college’s request to consider the bakery employees as “limited purpose public figures,” a measure that would hold libel to a higher standard. Similarly, the judge ruled against a request to keep the protest flyers out of the case, despite the college’s claim the flyer was “constitutionally protected opinion.” Miraldi will also consider allowing the plaintiffs to include text messages, emails and social media posts made by Oberlin faculty and students on a case-by-case basis.

There’s also the issue of whether an Oberlin student senate resolution passed Nov. 10, according to the suit—a day after the shoplifting incident—could be used as evidence of libel and slander. The resolution stated that Gibson’s “has a history of racial profiling and discriminatory treatment of students and residents alike” and that the store’s employees “were never detained and given preferential treatment by [police] officers.”

Oberlin police records show that Gibson’s had 33 shoplifting cases involving college students in the previous year, which involved 26 whites, five African Americans and two Asians, according to the lawsuit and information obtained by the ABA Journal.

If Oberlin was simply trying to organize and provide safety for students during the protest, then the First Amendment allows them to do so, Volokh adds.

“But it is very perilous to get involved in such behavior because in this case a jury will have to separate what is the law and to keep their personal opinions of those laws out of their deliberation,” he says.

Free speech and opinion expression are guaranteed by the Constitution, but there are different civil tort law standards of what is allowed and what is not, based on whether the harm is alleged against private individuals or businesses, versus public individuals or government groups. Most of the time, when universities are involved in free speech issues, these are cases determining whether they are allowing a controversial speaker to express their opinions on their campuses or whether they are restricting certain students’ groups from protesting on their campuses.

For example, the University of California at Berkeley recently was sued by a conservative student group that claimed the school’s administration had suppressed constitutionally protected expression in 2017 by limiting high-profile conservative speakers, while more leftist-leaning speakers had no such restrictions. The lawsuit was settled out of court.

In this case, however, Oberlin is being accused of being the speaker, not the event sponsor. The difference means that Gibson’s doesn’t have to show that Oberlin was actually malicious to prevail in its defamation suit, because of its private individual and/or business status. The plaintiffs must simply show the defendant was negligent or at fault.

On the contrary, however, the Supreme Court also has ruled that private defamation plaintiffs can’t recover punitive damages unless they do show evidence of actual malice.

LOOKING AHEAD

An Oberlin spokesperson gave a statement last week to the Oberlin Review about the college’s likely defense: “Colleges cannot be held liable for the independent actions of students. Employers are not legally responsible for employees who express personal views on personal time. The law is clear on these issues.”

Gibson’s, in its court filing, is claiming that such messages were part of a larger expression by the school to “leverage their power in a small community” against a small business. And the school is doing so to cater to their “social justice warrior” students, as competition for students by small, private schools is intense these days.

The case is expected to last until the end of May.

Daniel McGraw is a freelance writer living in Lakewood, Ohio. Find him on Twitter at @danmcgraw1.