1945-1954: Footnote 4

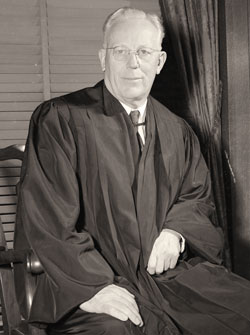

Photo of Chief Justice Earl Warren by AP Photo

The Carolene Products Co. was convicted of marketing a compound called Milnut—skim milk and coconut oil mixed to resemble condensed milk. It violated a federal law prohibiting the interstate sale of milk or cream blended with fat or oil other than milk fat, on grounds that such a mixture was a health hazard. The company sued, arguing the statute exceeded Congress’ powers under the commerce clause and the due process clause. In 1938 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the law, stating that there was a rational purpose for Congress to pass it.

But the court added Footnote 4, which implied that there may be an opportunity to examine more carefully any statutes that restrict political processes or violate the 14th Amendment, or that require greater attention to laws that “prejudice … discrete or insular minorities.” If the Supreme Court could address individuals who are denied the rights of citizenship, it could herald a refreshing approach to ensuring democracy.

Legal historians say Footnote 4 provided the court’s guiding principle on equal rights, and when California Gov. Earl Warren took over as chief justice in 1953, he was already facing a daunting challenge: a pile of school desegregation cases from four states and the District of Columbia, named for the case from Topeka, Kansas: Brown v. Board of Education. In one of his first conferences, several justices said Warren made clear that segregation had no place in contemporary America and asked how the court could reach unanimity.

As a recess appointment after the sudden death of Chief Justice Fred Vinson, Warren wasn’t officially confirmed by the Senate until March 1954. Two and a half months later, the court announced one of the most compelling rulings in American history. Brown, the 13-page decision that abolished separate but equal education, set the stage for a remarkable series of cases that attempted to liberate individuals from government pressure: Baker v. Carr (1962), giving the court jurisdiction to equalize voting districts; Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), stating that all indigent criminal defendants must be provided counsel; New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), narrowing libel laws; Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), recognizing the right of privacy; and Miranda v. Arizona (1966), specifying that suspects under arrest must be told their constitutional rights.

Meet the Warren Court. AP Photo

In the wake of school desegregation confrontations in Little Rock, Arkansas, the court passed one of its most far-reaching decisions upholding its supremacy in determining the law of the land, regardless of what state governments may desire. To many scholars, Cooper v. Aaron (1958) represents the high-water mark of the Warren court, an assertion of judicial prerogative that critics still claim is an unconstitutional misappropriation of power. Many said the Warren court pressed judicial review too far, claiming that the Constitution meant exactly what the court said it meant.

The reaction to Brown and the Warren court’s criminal justice cases was also harsh. The “Southern manifesto,” a credo signed by a majority of Southern legislators, called Brown an abuse of power. Southern states sought to intimidate the NAACP; Alabama required the association to reveal the names and addresses of its members and agents. The high court rejected that law in a 1958 case. Nor did the criticism stop there. Moderates claimed that law was scanty in cases such as Brown and Miranda, and they questioned whether the court was delving into social engineering. In addition, many of the court’s cases opened the field to more progressive decisions; Griswold’s right of privacy in contraceptive issues was a precedent for 1973’s Roe v. Wade. Indeed, the current political and legal climate is still reacting to the Warren court, with stricter limitations on abortion rights, Miranda exceptions and curtailment of voting rights.

But the fate of Brown is perhaps best revealed in a 2007 Supreme Court case: Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1.

The more conservative Roberts court rejected two school districts’ desegregation plans, saying they may not integrate through explicit accounting of a student’s race. Both sides in the ruling claimed to be faithful to Brown. For Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” In dissent, Justice Stephen G. Breyer read from the bench, saying wistfully, “It is not often in the law that so few have so quickly changed so much.”

In 2014, Brown v. Board of Education celebrated its 60th anniversary. Photo ©Bettmann Corbis.

100 Years of Law |

|

| « 1935-1944: A New Deal | 1955-1964: Civil rights struggle gains momentum » |