A Fox Rerun: Justices Get a New Look at the Old Problem of Dirty Words

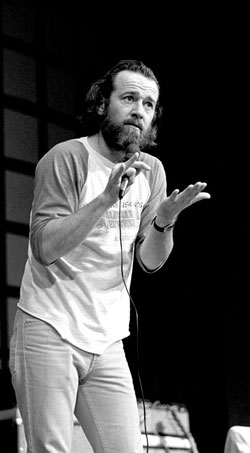

Photo of George Carlin by Ted Strehinsky/Corbis

For the U.S. Supreme Court, the case of Federal Communications Commission v. Fox Television Stations Inc. will be a bit like a TV rerun. It’s a show most of the justices have seen before.

The characters and the dialogue haven’t changed much. There’s Cher and her use of the F-word at the 2002 Billboard Music Awards. There’s Nicole Richie and her use of the F-word and S-word at the same awards show on the Fox network a year later.

In 2009, the high court upheld the FCC’s findings that such isolated and fleeting vulgarities constituted broadcast indecency. But that case was decided solely on the question of whether the commission’s orders were arbitrary and capricious under federal administrative law. The court said they were not.

This time around, the stakes are much higher. The justices themselves have tinkered with the script, rewriting the question presented by the case as this: “Whether the [FCC’s] current indecency-enforcement scheme violates the First or Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.”

And, just as TV producers might do when they are seeking to boost ratings, the justices have added a hint of nudity to the story. While the 2009 version in the Supreme Court was based only on the words uttered at the two Billboard Music Awards shows, the 2012 case also encompasses an FCC finding of indecency in a 2003 episode of the ABC show NYPD Blue.

PARENT-APPROVED

The case is hugely important for broadcasters and for media consumers. The federal government argues that it has a significant interest in protecting children from nudity and indecent language on the airwaves.

“The [FCC’s] indecency-enforcement rules remain a reasonable and constitutional implementation of the government’s compelling interest in protecting children from harmful exposure to sexual or excretory words and images,” U.S. Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli Jr. says in a brief on behalf of the commission and the Obama administration. “Generations of parents have relied on indecency regulation to safeguard broadcast television as a relatively safe medium for their children.”

Broadcasters argue that the FCC’s indecency policy as amended in 2004 has led to arbitrary definitions and discriminatory enforcement, as well as big fines.

For example, the FCC ruled that the F-word and S-word in TV broadcasts of the film Saving Private Ryan were not indecent because they were integral to the “realism and immediacy of the film experience for viewers.” But the commission found the same words indecent when public television aired Martin Scorsese’s The Blues: Godfathers and Sons.

And the FCC has found variants of the S-word, including “bullshit” on an NYPD Blue episode, to be indecent because they invoke a “coarse, excretory image,” but words and phrases such as “ass” and “load of crap” were not deemed indecent.

The NYPD Blue episode at issue was not the notorious one in which Detective Andy Sipowicz (actor Dennis Franz) bared his bottom, but a 2003 one called “Nude Awakening.” In the episode, Sipowicz’s son walks in on his dad’s new love interest as she prepares to take a shower, leading to embarrassment for both. The female character’s buttocks were shown for a total of seven seconds, ABC says in a brief, but the show came with parental advisories and a mature rating.

After viewer complaints, the FCC found the episode indecent, calling the extended views of the woman’s buttocks “pandering, titillating and shocking.” The commission fined ABC and its stations $1.24 million.

Seth P. Waxman, the Washington, D.C.-based lawyer representing ABC in the high court, argues that the FCC’s indecency standards are vague and provide little meaningful help to broadcasters in complying with the law.

The FCC’s “inconsistent decision-making appears driven by the commissioners’ personal views about the merits of particular programming,” Waxman said in his brief. “And … broadcasters’ constitutionally protected expression has been severely chilled as a result.”

He notes that some ABC affiliates declined to carry Saving Private Ryan in 2004, fearing indecency complaints. (The commission’s rejection of indecency complaints came the next year.) And that under federal law, the FCC has the authority to impose “draconian” fines of up to $325,000 per station for indecency violations.

A COARSENING OF THE AIRWAVES

Fox wasn’t fined for the indecency in its Billboard telecasts because the FCC didn’t change its policy on isolated expletives until 2004. In the 2002 show, Cher said “Fuck ’em” to her critics when she accepted an award. In 2003, Richie, then a star of the fish-out-of-water reality show The Simple Life, said, “Have you ever tried to get cow shit out of a Prada purse? It’s not so fucking simple.”

Fox, joined by CBS and NBC, argues that the time has come for the Supreme Court to overrule its 1978 decision in FCC v. Pacifica Foundation. That ruling regarded a complaint to the commission over a radio station’s airing of comedian George Carlin’s famous monologue about words that could not be said on TV.

In Pacifica, the high court upheld against a First Amendment challenge the FCC’s finding that the broadcast was indecent. The court noted that broadcasting was “uniquely pervasive” in the lives of Americans, and that material presented over the airwaves confronts the viewer or listener in the home. The court observed that broadcasting was uniquely accessible to children, and that the airing of indecent language can “enlarge a child’s vocabulary in an instant.” The justices found repetitive, deliberate use of certain words that referred to excretory or sexual words or organs in an afternoon broadcast when children were listening to be indecent.

Carter G. Phillips of D.C., who will argue the case for Fox, NBC and CBS, says that for more than two decades, broadcast media have been treated as second-class citizens under the First Amendment. Meanwhile, the mass media marketplace has changed dramatically, eroding the foundation for the Pacifica ruling.

“The rationale that the court has always put forward for a lower standard was that the TV networks were uniquely pervasive,” Phillips says. “That arguably was true in 1978, but it has not been true for at least a decade. Yet the court has not revisited the question of what kind of constitutional standard ought to apply to the broadcasting industry.”

To the Parents Television Council and other allies of the FCC and its indecency-enforcement efforts, the episodes at issue typify the increasingly coarse content that pervades broadcasting. In an amicus brief on the government’s side, the Los Angeles-based council cites its own study showing that the use of profanity on prime-time broadcast entertainment shows increased 70 percent from 2005 to 2010. Even bleeped or muted uses of the F-word went from 11 instances in 2005 to 276 instances in 2010, the council said.

“It may be that there are these other channels of communication” in today’s media marketplace, says Robert R. Sparks Jr. of McLean, Va., the lawyer for the 1.3 million-member grassroots group. “But the court stressed in Pacifica that what sets broadcast apart is that it is uniquely accessible to children.

“I think the court is going to find a way to permit the FCC to do what Congress has told it to do, and that is to keep some modicum of decency on the broadcast airwaves until 10 at night,” Sparks says. “After 10, they can put on The Sopranos if they want.”

An amicus brief on the broadcasters’ side signed by several former FCC commissioners, including former chairmen Mark Fowler and Newton N. Minow (who in the 1960s dubbed television a “vast wasteland”), argues that the commission has embarked on a “Victorian crusade” against a radically enhanced definition of indecency. The brief adds that the commission is unduly influenced by computer-generated complaints by the Parents Television Council and other groups.

“Broadcasting is no longer unique, and it is time for the court to bring its views of the electronic media into alignment with contemporary technological and social reality,” the brief says.

When the Supreme Court upheld the FCC’s actions under the Administrative Procedure Act two years ago, the court all but predicted the case’s return on the constitutional questions it has now put forth.

“If the reserved constitutional question reaches this court, we should be mindful that words unpalatable to some may be ‘commonplace’ for others, ‘the stuff of everyday conversations,’ ” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said in a dissent, quoting the dissent of Justice William J. Brennan Jr. in Pacifica. Two other justices in dissent on the administrative issue, John Paul Stevens and David H. Souter, have since retired. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who succeeded Souter, is sitting out the case.

Justice Clarence Thomas, who joined the majority opinion three years ago that upheld the FCC on procedural grounds, nevertheless invited the challenge to the vitality of Pacifica, as well as an older precedent on broadcast regulation. “Traditional broadcast television and radio are no longer the ‘uniquely pervasive’ media forms they once were,” Thomas said in his 2009 concurrence.

With the justices finally getting to the biggest constitutional questions, they have set the scene for a blockbuster June finale for this long-running TV drama.